eBook - ePub

Moulding the Female Body in Victorian Fairy Tales and Sensation Novels

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Moulding the Female Body in Victorian Fairy Tales and Sensation Novels

About this book

Laurence Talairach-Vielmas explores Victorian representations of femininity in narratives that depart from mainstream realism, from fairy tales by George MacDonald, Lewis Carroll, Christina Rossetti, Juliana Horatia Ewing, and Jean Ingelow, to sensation novels by Wilkie Collins, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Rhoda Broughton, and Charles Dickens. Feminine representation, Talairach-Vielmas argues, is actually presented in a hyper-realistic way in such anti-realistic genres as children's literature and sensation fiction. In fact, it is precisely the clash between fantasy and reality that enables the narratives to interrogate the real and re-create a new type of realism that exposes the normative constraints imposed to contain the female body. In her exploration of the female body and its representations, Talairach-Vielmas examines how Victorian fantasies and sensation novels deconstruct and reconstruct femininity; she focuses in particular on the links between the female characters and consumerism, and shows how these serve to illuminate the tensions underlying the representation of the Victorian ideal.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Moulding the Female Body in Victorian Fairy Tales and Sensation Novels by Laurence Talairach-Vielmas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

‘That that is, is’

The Bondage of Stories in

Jean Ingelow’s Mopsa The Fairy (1869)

‘That that is, is; and when it is, that is the reason that it is.’1

Weaving the Threads of Feminine Representation

As illustrated by Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland whose final trial shows Alice trying to hold the pen which might enable her to rewrite her self, patriarchal Western culture forbids women the pen. Standing as a representation of power ‘made flesh’,2 the literary text is fathered, in Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s terms, by ‘an aesthetic patriarch whose pen is an instrument of generative power like his penis’3—hence, the impossibility for woman to bring it to being. In the field of fairy tales, however, the story of women’s struggle for the pen is a long battle. Before the nineteenth century, folk tales and fairy tales were a feminine province. Oral folklore was passed on from old women of low status to little girls, from nurses to children, with the recurrent figure of Mother Goose, as the ‘typical purveyor of old wives’ tales.’4 Both grotesque and wise, sententious and foolish, Mother Goose focused her stories on young women, hinging the plots most significantly on the particular event which governs woman’s life: marriage. The figure of the teller thus shaped the fairy-tale mode as a repository of female experience and of female viewpoint. Regarded as a marginal genre associated with the lower classes, with oral lore and unofficial culture, primitive knowledge, it gave women the opportunity to phrase their experience, even if, as Marina Warner suggests, this body of stories figuring wicked stepmothers and disobedient heroines ‘defame[d] them … profoundly.’5 Moreover, as Mother Goose’s stories gradually invaded dominant culture in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, being retold by précieuses, this aboriginal female wisdom left the margin to settle in salons and voice women’s power.6 By means of narrators holding the threads of complex and intricate stories and deciding the characters’ fate, or through female characters casting spells and playing with language, women could voice their discontent and abandon the confining working-class model of the fairy-tale teller for the more glamorous figure of the fairy-tale woman writer.

But women did not long remain the ‘guardians of language’, in Warner’s words.7 Mother Goose was soon recaptured by male writers and collectors eager to give their stories a touch of authenticity. In this way, the feminine territory of the fairy tale was gradually colonized.8 When the Brothers Grimm refashioned fairy tales in the 1830s, they manifestly instilled dominant (male) social standards in children’s narratives so as to educate and police children.9 Hence their framing of the tales as cautionary or exemplary tales where women are either idiots, or cruelly punished for their sins, from being starved to being dismembered.10 The brutality of the punishments inflicted on female characters in early nineteenth-century tales11 demonstrates the influence of patriarchal ideology on the tales’ morality: on the literary battlefield, women were beating a retreat, and their narratives hardly sounded as militant as those of their foremothers.12

In the second half of the nineteenth century, however, not only did fairy tales blossom in England—while they had been so far distrusted by a Puritan culture praising reason and condemning imaginative genres—but they also ostensibly reworked the ideological indoctrination of children that traditional tales, like those by Perrault or the Brothers Grimm, aimed at. The bourgeois codes of conduct which mark the tales of the Brothers Grimm and later those of Hans Christian Andersen were revised in the second half of the nineteenth century when the discourse of the 1860s experimental fairy tales and fantasies denounced the norms and manners of society in a radical way. Turning morality upside down, the Victorian fairy tales welcomed their readers through the looking-glass, and the fairy tale became a potentially subversive territory whose links with Victorian reality were strengthened the better to voice protests against the dominant culture. Because the innocence of Victorian children remained unquestioned, subversion was more likely to go uncensored in children’s literature after 1860,13 and fairy tales could thus easily become double-edged. They could either feature the romantic scenario awaiting the heroine or subversively expose the preset plot-pattern which denies the heroine freedom both literally and textually. Often hovering between romance and reality, poised between fairy realms and domestic realism, Victorian fairy tales and fantasies manifestly bridged a significant gap between two alien lands, emphasizing fairy ideals in order to underline the inadequacy of the fairy-tale mode in the exploration of women’s lives and predicaments in patriarchal society.

As suggested, when the eighteenth-century French conteuses took up the pen in aristocratic salons and reworked their female ancestors’ story-telling into an aesthetic literary activity, they ambiguously positioned themselves between low and high culture, simultaneously drawing on a female literary subculture and stealing a male prerogative. Mediating ‘between the male artist and the Unknown’,14 these women writers of fairy tales epitomized the figure of the woman writer, excluded from culture, and which Gilbert and Gubar construe as ‘an embodiment of just those extremes of mysterious and intransigent Otherness.’15 Because they precisely dealt with fantasy’s dark underworlds, inhabited by goblins and witches, they could explore from their own viewpoint the male images on the surface of the glass which imprison women as angelic or monstrous extremes, through clichés binding both female characters and women writers. By snatching up the male pen, they could rewrite the female body, foreground female power, or denounce tales precast by masculine preference.

This idea is even more significant for Victorian fairy-tale writers and fantasists writing against the backdrop of Darwinian theories of biological and cultural evolution. Featuring heroines fighting against their own bestial greed, their own otherness, Victorian fairy-tale writers and fantasists probed the texture of women’s literature even deeper. Their underworlds tackled Otherness through heroines and texts dangerously hovering on the outskirts of the dominant culture and provided a relevant means of penetrating the looking-glass of the dominant realistic order. Indeed, while the fairy tales of the 1860s and 1870s aimed to undercut the dominant culture, Victorian women fairy-tale writers and fantasists particularly underlined the constraining processes that inhered in the preset plot-patterns of such tales and which haunted Victorian narratives more generally, as ideal case scenarios. If the prevalent association of women and children throughout the nineteenth century did not make it easier for women writers to write fantasies, the wilder romances of women fantasy writers of the 1860s and 1870s testified to the idea that women writers—unlike most contemporary male writers—hardly sought to stunt their heroines’ growth in childhood.16 On the contrary, fairy tales and fantasies were a means of pointing out their own situation and of debunking and revisiting the clichés and stereotypes that served to further their definition as passive angels crystallized in glass coffins and palaces. Making explicit how tales concealed a ‘harshly realistic core’17 beneath their fairy surface, women writers used wonders in order to move along a continuum between the real and the fantastic. Throughout the narratives, the real and the fantastic fuel one another, and fairy tales cloak women’s harsh reality in order to enable women to investigate their own construction from a distance. Women’s reappropriation of a genre fraught with patriarchal and normative constructs casts, therefore, new light on Victorian reality, redefining reality through fairy tales and fantasies hovering between antagonistic realms, but never really severed from reality.

Textually speaking, in most of the fairy tales and fantasies of the era, the links between fantasy and Victorian reality are often operated through some modern revisiting of the clichés which conventionally frame woman. In Carroll’s Alice, as we shall see, the prevalence of signification problems in the fantasy world posits signs and letters as key figures standing between the real and the magic realm, turning the latter into an experimental place in which to envision the workings of representational codes. As female identity stems from tropes such as, for instance, sweet little girls who literally feed on treacle and become sweet, as cards are numbers, or even, in Tenniel’s illustration, as the hatter proudly wears a hat of his own making which figures its price, the heroine discovers that her self is made up of such signs. As we shall see, slowly becoming semioticized, Alice’s journey through language is also a journey through consumer culture until she finally becomes commodified as fragile ware in Through the Looking-Glass: ‘Lass, handle with care.’ The very glass metaphor incarcerates her into a cliché, both literary and visual, as shall be seen in chapter 5. For Victorian women fantasists, on the other hand, if such modernity sometimes underlies the narratives, their use of the fairy-tale mode generally plays less with such defamiliarizing processes than it questions the way in which an originally feminine genre can define female writing and feminine identity. While hints at consumer culture are discreetly encoded, their exploration of signs and letters is embedded in a general discourse on representation which underlines the limits of female creativity and freedom and heightens woman’s incarceration by literary devices.

Indeed, Victorian women fantasists frequently revisit representations of female literary activity by drawing on the fairy-tale mode and revivify the tradition of the old storyteller or female weaver in order to examine how women’s plots pictured woman. Rather than offering an alternative version of reality, their use of fantasy functions as a means of exploring the genre’s representational tools and of ‘repossess[ing] an imaginative tradition they regard as their own.’18 In fact, by reappropriating a feminine mode of writing, fairy-tale women writers lay bare their own viewpoint on traditional modes of feminine representation and propose a bleak picture of fantasy’s potential power where woman can hardly escape male-defined images.

Jean Ingelow (1820–1897) was a Victorian writer, praised and promoted by John Ruskin, who published her first work anonymously (A Rhyming Chronicle of Thoughts and Feelings) in 1850. Though she was modest and self-effaced, her fame was sealed with the success of her first volume of poems, published in 1863, followed by The Story of Doom and Other Poems in 1867; her last volume of poems was published in 1885. Ingelow could write both novels for adults (Allerton and Dreux [1851], Off the Skelligs [1872], Fated to be Free [1875], Sarah de Bergener [1879], John Jerome [1886]) and juvenile literature. Her children’s fiction, Studies for Stories (1864), Stories Told to a Child (1865), and A Sister’s Bye-Hours (1868) are collections of her contributions to the evangelical Youth’s Magazine under the pseudonym of ‘Orris.’ If her poems contain little feminism, her fiction features women trying to break free from a patriarchal society ruled by laws unfair to women. In Sarah de Bergener, Hannah Dill inherits money from her uncle and decides to use it to free herself from her husband, a convicted criminal, to whom the money legally belongs. In another significant instance, Mopsa the Fairy, Ingelow clearly reworks Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: a boy finds fairies, one of whom, Mopsa, is to become a queen. The fantasy then traces Mopsa’s journey from innocence to experience: Ingelow’s heroine, ruling over her kingdom, seems fated to yield to some scripture sentencing her to grow into a woman. In fact, Mopsa experiences the construction of femininity as a literary journey where tales are woven and femininity is elaborated on skeins. Confined within stories, Mopsa is imprisoned by enchanted words. Revealingly, these words which enslave women are bound to material culture and pinpoint the links between feminine representation and Victorian consumer society.

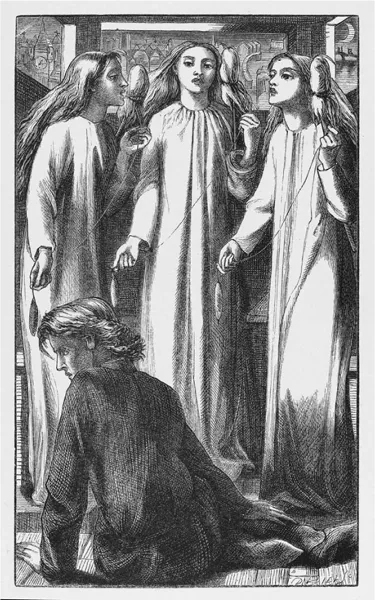

1.1 Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Maids of Elfen Mere, 1855. From William Allingham, ‘The Maids of Elfen Mere’, in The Music Master: A Love Story and Two Series of Day and Night Songs (London: Routledge, 1855).

Ingelow’s Fairyland and the Marketplace

In his illustration for William Allingham’s poem ‘The Maids of Elfen Mere’ (1855), Dante Gabriel Rossetti brings into play unexplored aspects of the narrative and foregrounds the invisible threads which fuel many a fairy tale and upon which Ingelow’s Mopsa the Fairy draws. Indeed, in ‘The Maids of Elfen Mere’ three enchanting fairies spin and sing every night and vanish once the clock strikes eleven. Bewitched and enamoured, a young man puts the clock back one night so that the fairies may remain longer. But at eleven, the three fairies melt into the lake, leaving but three blood stains. Unlike Allingham, instead of positioning the three fairies as victims of man’s desire and letting their bodies melt away, Rossetti chooses to play upon the etymology of the word ‘fairy’ to represent the women as powerful and potentially threatening.

Originally, the word ‘fairy’ derives from a Latin feminine word, fata, a variant of fatum (fate), itself referring to a goddess of destiny and literally meaning that which is spoken.19 Fairies can thus both tell the past and the future. Interestingly, in Rossetti’s illustration, the three fairies are fashioned as three tall women mesmerized by the spindles they are holding. As a representation of the threefold nature of time—the past, already wound around the spindle, the present, illustrated by the thread drawn between their fingers, and the future twined on the distaff20—Rossetti’s fairies metamorphose into Fates as the young man, sitting on the floor, looks away from their medusa-like gaze. Rossetti’s illustration of women holding the thread of life illuminates the power inherent in women’s spinning, whether literally or figuratively spinning stories as Mother Goose. Female stories act like scriptures and become a dangerous activity where man is cast out of the realm of female imagination.

The image of women as tellers and foretellers detaining power abounds all through the Victorian era. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s painting of his entranced wife in Beata Beatrix (1864), envisioning her own death and hovering between the realms of the living and the dead, is a stunning mid-century representation of woman as seer or sybil. Metamorphosing from victim to powerful queen, as Nina Auerbach suggests, woman ‘shak[es] off the idiom of victimization’21 to exhibit matriarchal power. At the opening of George MacDonald’s Phantastes (1858), the hero discovers a tiny woman in his father’s old secretary. Drawn by the pe...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Femininity through the Looking-Glass

- 1 ‘That that is, is’: The Bondage of Stories in Jean Ingelow’s Mopsa the Fairy (1869)

- 2 MacDonald’s Fallen Angel in ‘The Light Princess’ (1864)

- 3 Drawing ‘Muchnesses’ in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

- 4 Taming the Female Body in Juliana Horatia Ewing’s ‘Amelia and the Dwarfs’ (1870) and Christina Rossetti’s Speaking Likenesses (1874)

- 5 A Journey through the Crystal Palace: Rhoda Broughton’s Politics of Plate-Glass in Not Wisely But Too Well (1867)

- 6 Investigating Books of Beauties in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1853) and M.E. Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1862)

- 7 Shaping the Female Consumer in Wilkie Collins’s No Name (1862)

- 8 Rachel Leverson and the London Beauty Salon: Female Aestheticism and Criminality in Wilkie Collins’s Armadale (1864)

- 9 Wilkie Collins’s Modern Snow White: Arsenic Consumption and Ghastly Complexions in The Law and the Lady (1875)

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index