eBook - ePub

The Politics of Unemployment in Europe

Policy Responses and Collective Action

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book offers a state-of-the-art discussion of the political issues surrounding unemployment in Europe. Its unique combination offers both a policy and institutional perspective, whilst studying the viewpoint of individual civil society members engaging in collective action on the issue of joblessness. It is the result of Marco Giugni's three year cross-national comparative research project, financed by the European Commission, united with hand picked contributions from invited experts. Throughout his study he focuses on how the EU approaches national unemployment, the main national differences in talk about unemployment and unemployment policy, and how the representatives of the unemployed produce and coordinate demands in relation to unemployment policy. This book contains a number of genuinely cross-national chapters along with sections on specific national cases, namely the UK, Ireland, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium and Sweden.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Politics of Unemployment in Europe by Marco Giugni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Unemployment and Social Protection

Bengt Furåker

Gainful employment is the way in which most working-age people earn their living in modern societies, and unemployment is therefore a major social and economic problem. Those individuals who offer their labouring capacities in the market but find nobody willing to hire them run the risk of having no income and of encountering various other difficulties (see, e.g. Alm 2001, Gallie 2004, Gallie and Paugam 2000, Nordenmark 1999, Strandh 2000). However, to counteract this, contemporary welfare states provide some degree of social protection for people who are, or are likely to become, unemployed. This chapter deals with issues related to how the state in advanced capitalist countries handles unemployment.

State intervention with respect to unemployment or potential unemployment involves legislation, transfers of income and direct services. It can be classified in many different ways and for the following analysis and discussion I distinguish three principal types. These do not make up an exhaustive list of all relevant state policies, but all three are certainly at the centre of policy discussions. First, I will pay attention to employment protection legislation (EPL) that is generally oriented towards making it more difficult and/or more costly for employers to lay off workers. The overall purpose is to reduce the risk of workers being arbitrarily or quickly dismissed, and suddenly having no job and no income. It is a kind of intervention designed to reduce the likelihood of people becoming unemployed in the first place.

The second category covers financial support for individuals who have become unemployed and therefore cannot provide for themselves. Under the concept of passive labour market policy (PLMP) there are two subcategories. One of them is a matter of different forms of cash benefits paid to people who have no job and who are, or at least should be, jobseekers. In this case, I utilize the term ‘unemployment compensation’ (UC). The other PLMP subcategory refers to pension programmes allowing early retirement for labour market reasons. People who have enduring difficulties in finding employment are supported financially so that they can leave the labour market. Such programmes exist only in some of the advanced capitalist countries, but should be taken into consideration.

Finally, we have active labour market policy (ALMP), in principle organized for the purpose of putting people to work. This goal is supposed to be attained with the help of public employment services (job-search assistance, counselling, etc.), training programmes, subsidized jobs, job creation and certain other measures. Of course, to some extent ALMPs have the same function as PLMPs of providing an income to the unemployed, but their distinctive feature is their further aim of getting people into jobs. There is thus a difference in the level of ambition, which can also explain why the adjectives ‘passive’ and ‘active’ are being used. We may have doubts about the appropriateness of these words, but they belong to the standard terminology in the literature and I will therefore stick to them.

The three policy types to be focused on here – EPL, PLMP and ALMP – affect labour markets in different ways. As hinted above, they are not the only ways in which the state intervenes with respect to unemployment; in fact, there are several other policies (e.g. general economic policies, public childcare and education) that also play important roles. However, if we want to concentrate on a few core aspects of social protection in connection with unemployment, it goes without saying that EPL, PLMP and ALMP must be focal points. One essential aspect is that all three policies are called into question as to whether they actually accomplish what they are set up for. Sometimes it is argued that they have negative effects on unemployment and employment. This whole debate is part of the general discussion on whether the modern welfare state is, or can be, successful in its efforts to come to grips with social and economic problems. I want to provide an overview of issues related to the functioning of EPL, PLMP and ALMP in developed capitalist countries and to discuss these issues in the light of previous research and some empirical data from recent years (see also, e.g. Furåker 2002, 2003a, b).

Employment Protection Legislation

In the main, EPL includes a set of rules prescribing under what circumstances and how employers can carry out dismissals (individual and collective) and what rights workers have to keep their jobs. It can define legitimate causes for dismissal and specify rules regarding procedural matters, time of notice, severance pay, etc. Another purpose of the legislation is to provide a legal framework for the establishment of fixed-term employment contracts.

There are several studies on the role of EPL and they show somewhat inconclusive results (see, e.g. Baker et al. 2005, Bertola, Blau and Kahn 2002, Esping-Andersen 2000a: 84–90, OECD 1999: Ch. 2, 2004: Ch. 2). Among other things, these studies have tried to establish whether strict legislation has counterproductive effects, above all whether it leads to higher unemployment and lower employment. The explanation as to why such effects might appear goes something like this. If the law makes it difficult and costly for employers to get rid of workers when they need to do so (for example in a recession), they become restrictive with hiring people. Consequently, employment rates may be lower than they would be without this legislation. Moreover, employers are also expected to become selective with whom they hire. When layoffs are costly, it is especially important to hire only people who are well suited for the jobs and who are not likely to involve any risk-taking. In other words, strict EPL may increase the difficulties of finding work for certain vulnerable categories, and these individuals may accordingly run a greater risk of ending up in unemployment.

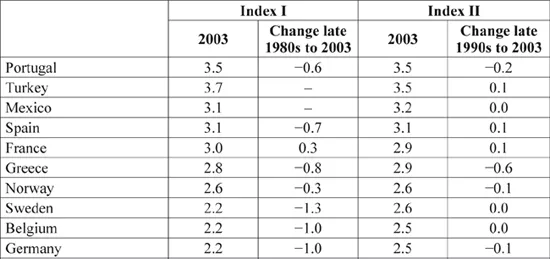

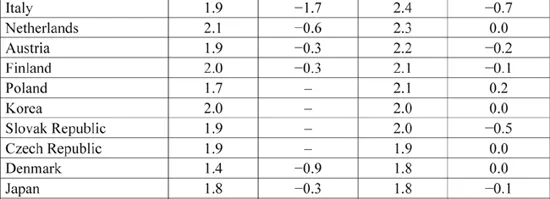

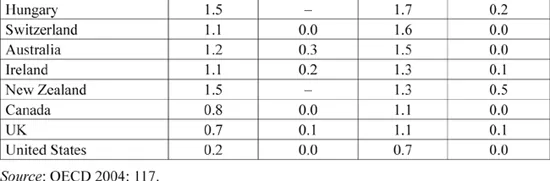

The most recent study done by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD 2004: Ch. 2) analyses the changes in EPL from the late 1980s up to and including 2003. Various countries are compared regarding strictness of EPL with the help of two indices. One is presented for the late 1980s, the late 1990s and 2003 and the other only for the late 1990s and 2003. Actually, the two indices are strongly correlated with one another – the second version involves only minor adjustments – so it does not matter very much which one we choose to use. Both of them are based on the legislation concerning three dimensions: regular employment, temporary employment and collective dismissals. In Table 1.1 both indices are included. The higher the scores, the more restrictive is the legislation. Countries are ranked according to the degree of strictness in 2003 (Index II), with the strictest at the top and the most liberal at the bottom of the table.

We find the highest scores on Index II for Portugal and Turkey, with Mexico as number three and Spain as number four in the rank order. With Index I, the picture at the top is roughly the same. Southern European countries generally have high figures, but it should be observed that Italy has liberalized its EPL substantially over recent decades. At the bottom of the table, we come upon the United States, somewhat below the UK and Canada. The other Anglo-Saxon countries also have low scores. Most of the central European and the Nordic countries are somewhere in between. As we can see, there is no common Nordic model; Norway and Sweden have relatively high figures, whereas Finland and, in particular, Denmark score clearly lower.

Looking at changes over time, we discover that a number of countries have become more liberal, but the picture is somewhat divided. Data for the changes between the late 1980s and 2003 (Index I) are available for 20 of the 28 countries in the table. Scores then decreased in 13 cases (most of all in Italy, followed by Sweden, Belgium and Germany), but increased in four cases and remained stable in three cases. Comparing the late 1990s and 2003 (with Index II), we have access to data for all 28 countries and nine of them had lower scores in 2003, eight had higher scores, and 11 had unchanged scores. With respect to change, although EPL has become less strict in many countries, it can be concluded that there is rather strong continuity over the years (OECD 2004: 71–5).

The question is then to what extent EPL affects unemployment and employment rates. According to the OECD (2004: 76-8), strict EPL tends to slow down the flows of people from employment to unemployment. This is simply in line with the purpose of the law, that is, to give workers some protection against hasty dismissals. With the exception of the Nordic countries, there is a similar indication regarding flows from unemployment (to employment or out of the labour force). It is not, however, statistically significant. Unfortunately, in the OECD report, transitions from unemployment to jobs are not kept separate from transitions from unemployment out of the labour force. The theoretical assumption is anyhow that strict rules make employers more restrictive with hiring. Consequently, the total impact on the level of unemployment can be expected to be low, because two forces are supposed to be in operation and they go in opposite directions. According to the OECD (2004: 81), it cannot be verified that EPL strictness is associated with high overall levels of unemployment, but it appears that the incidence of long-term unemployment is affected.

Table 1.1 EPL scores according to two indices – 2003 and change since late 1980s and late 1990s: Rank according to Index II scores 2003

Furthermore, the OECD (2004: 81–6) calls attention to the impact that EPL has on the demographic composition of employment. If employers become more restrictive with hiring people, certain categories are likely to run into increasing difficulties in getting a job. Consequently, strict rules seem to be a disadvantage for prime-age women and youths, whereas prime-age men and older workers tend to be favoured.

It needs to be noted that temporary jobs are to some extent functional alternatives to liberal legislation. Given that the possibility of establishing temporary employment contracts is not too limited, we can expect them to be used more often in countries where EPL is generally strict. There is also empirical support for this assumption (OECD 2004: 87; see also Hudson 2002: 40–42). Moreover, the step from temporary to permanent employment contracts is negatively correlated with the strictness of legislation regarding permanent employment (OECD 2004: 87–8). When, in the latter respect, liberalization has taken place, it seems that the proportion of temporary contracts has decreased.

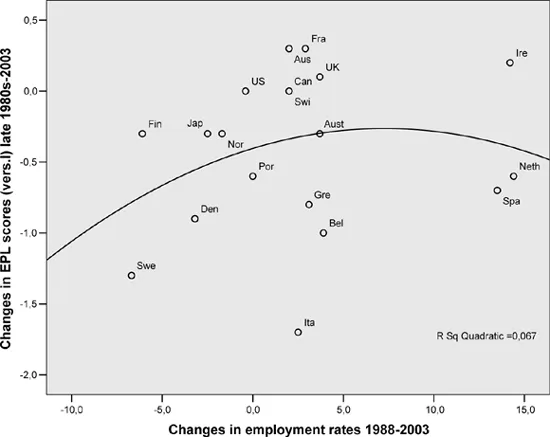

Using data for 2003 and 2002, respectively, the OECD (2004: 81) detects a statistically significant negative correlation between EPL (Index II) and employment levels. In other words, countries with less strict EPL tend to have higher employment rates, but, as emphasized in the report (OECD 2004: 80), a bivariate association is not enough for policy conclusions. We can just add that neither is it enough for scientific generalizations. To provide some further information on the issue, I shall examine what has happened with employment rates when EPL has been changed. If strict rules contribute to holding down employment levels, liberalization should be expected to increase these levels. Figure 1.1 presents the relationship between changes in EPL scores (Index I) between the late 1980s and 2003 and changes in employment rates 1988–2003.

For those who had expected that liberalization would be associated with higher employment rates, the picture presented in Figure 1.1 is likely to be disappointing. The relationship between the two variables is not negative but positive, although the correlation is far from statistically significant. When calculating the corresponding correlation between the changes from the late 1990s to 2003 (with Index II) and the changes in employment rates between 1998 and 2003, we get a similar outcome (not shown). Most importantly, these outcomes reject the hypothesis that liberalization of EPL would generally lead to increased employment. The reason is of course that employment rates are determined by so many other factors (the low R2 figure also suggests this). For example, in many countries a growing number of women have jobs, and to explain this we must obviously consider factors of a very different kind. Young people, on the other hand, stay longer in the educational system and their employment rates have therefore gone down.

In sum, there is no conclusive evidence that EPL in the economically developed Western countries can be blamed for their failures in terms of unemployment and employment. No doubt, given the way labour markets function, problems of this kind may appear if EPL strictness passes a certain point. Still, so far it appears that other factors are more critical for the problems in question. In this connection, we must be aware that fixed-term employment contracts are more widespread in countries with strict EPL, and such contracts can be seen as a compensatory mechanism that reduces the effects of strict rules. There is also another aspect that should not be forgotten. Strict legislation seems to lead to a redistribution of chances among people both to keep a job and to find employment, to the disadvantage of prime-age women and youths.

Figure 1.1 Changes in EPL scores and changes in employment rates, late 1980s to 2003

Notes: Aus = Australia; Aust = Austria.

Source: OECD 1992: 30, 2004: 117, 2005: 238.

Passive Labour Market Policies

As mentioned above, we have two types of PLMP. First, there are various forms of cash benefits (UC) to people who do not have a job and who are supposed to be jobseekers. Second, some countries provide early retirement pensions for labour market reasons. This kind of policy implies that people do not have to be available for work in order to fend for themselves; it gives them the opportunity, permanently or temporarily, to exit the labour market.

Most of the discussion on PLMP focuses on UC, probably because benefit recipients are expected to be active in looking for work and eventually to find and take a job. There is a never-ending controversy about whether benefits make the unemployed less eager in their job-searching activities and choosier with respect to employment offers. A common claim is that the benefit systems are too generous. The discussion then deals with issues such as replacement rates, ceilings, waiting days, duration of benefits, eligibility requirements and sanctions when people quit jobs voluntarily or refuse to take jobs offered. Regulations differ across countries and a detailed examination of a large number of rules is required to decide whether a given country has a more generous system than another (cf., e.g. Grubb 2001, OECD 2000: Ch. 4). Inspired by Francis Castles’s (1998: Ch. 6, 2004) analysis of welfare state developments, I have instead decided to focus entirely on expenditures; with the help of such data we have a less ambiguous way of making cross-national comparisons.

In the following we shall deal with two measures: PLMP and UC expenditures as a percentage of GDP and, more importantly, these proportions per percentage point of unemployment. The latter kind of calculation gives us a crude measure of the generosity of the systems. It ignores the details but summarizes how much each country spends on PLMPs or UC when we control for unemployment rates. Without this kind of control, figures would be misleading, because as soon as unemployment rises, costs go up, unless there is a reduction in the amount of money that benefit recipients can receive – or an increase in GDP.

Having emphasized the need for control of unemployment levels, we can turn to Table 1.2, where data for OECD member states on PLMP and UC expenditures are presented for one specific year. It can be added that the picture would be quite similar if other recent years were chosen. For most of the countries, data are provided for 2003. However, in Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, the UK and the United States they refer to the fiscal year 2003/2004 and I have then used average unemployment rates for 2003/2004 when calculating expenditures per percentage point of unemployment. As always, it is difficult to find data that are perfect for cross-national comparisons, although the information provided in Table 1.2 seems to be of fairly good quality. The perhaps most significant inconsistency applies to Spain, where costs for early retirement for labour market reasons are included in the UC figure and cannot be separated from it. Countries are ranked according to the proportion of GDP spent on PLMP per each percentage point of unemployment.

Starting with expenditures on PLMP as a percentage of GDP, we discover a great deal of variation across countries in 2003. Four countries – Denmark, Belgium, Germany and Finland – have figures hig...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction State and Civil Society Responses to Unemployment: Welfare, Conditionality and Collective Action

- 1 Unemployment and Social Protection

- 2 Adapting Employment Policies to Postindustrial Labour Market Risks

- 3 Work and Welfare: The Rights and Responsibilities of Unemployment in the UK

- 4 The Promises of Labour: The Practices of Activating Unemployment Policies in Switzerland

- 5 Trade Unions and the Unemployed in the Interwar Period and the 1980s in Britain

- 6 Belgian Trade Unions, the Unemployed and the Growth of Unemployment

- 7 Political Challengers, Service Providers or Service Recipients? Participants in Irish Pro-unemployed Organizations

- 8 Welfare States, Labour Markets, and the Political Opportunities for Collective Action in the Field of Unemployment: A Theoretical Framework

- 9 The Hidden Hand of the European Union and the Silent Europeanization of Public Debates on Unemployment: The Case of the European Employment Strategy

- Bibliography

- Index