eBook - ePub

Electronic Performance Support

Using Digital Technology to Enhance Human Ability

- 326 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Electronic Performance Support

Using Digital Technology to Enhance Human Ability

About this book

Despite ubiquitous powerful technologies such as networked computers, global positioning systems, and cell phones; human failures in decision-making and performance continue to have disastrous consequences. Electronic Performance Support: Using Digital Technology to Enhance Human Ability, reminds everyone involved in education, training, human performance engineering, and related fields of the enormous importance of this area. Ironically, the more complex technology becomes, the more performance support may be needed, and that's why the extraordinary expertise shared in this book is especially valuable. The authors emphasize the psychological aspects of performance support, the fundamental limitations of human memory, perception, cognition, conation, and psychomotor skills and how they can be reduced through electronic performance support, as one of the most important pursuits of this century. Readers will find the material presented extremely useful because of its generic basis - which underlines much of the contemporary use of electronic technology for supporting people who are engaged in problem-solving activities. At the same time, the book gives examples of the application of electronic performance support in a number of specific domains. Possible future developments for electronic performance support are also discussed. The technological challenges we face today, both globally and locally, are more urgent than most people seem willing to acknowledge, and there is no time to waste putting the ideas expressed in this book into action.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1 Introduction

This initial chapter of the book is intended to provide an introduction to the basic nature of performance support systems (in general) and electronic performance support systems (in particular). The chapter begins by introducing and describing the ideas underlying the use of the term ‘system’. It then identifies human-activity systems as being an important issue in relation to the material covered in subsequent chapters of this book. All humans have innate limitations; some of the major causes of these limitations are discussed and some of the consequences of these are illustrated using a selection of anecdotal evidence. Human behaviour and performance in any given task domain is critically dependent on the knowledge and skills that individuals possess. Because much of the work that is undertaken in the area of performance support relates to skill improvement, the chapter discusses the basic nature of skills and skilled performance – and how this may be improved through the use of different types of supportive intervention and/or performance aid. Consideration is then given to the importance of knowledge in relation to skilled performance.

Systems Orientation

In my introductory lectures on the subject of human-computer interaction (HCI), I tell my students that ‘everything is a system’. Indeed, according to many theorists, ‘the Universe consists of a set of interacting systems’. So, what exactly is a system? According to Ackoff (1972: p. 84), a system is a ‘set of interrelated elements’. In his definition, however, Jenkins (1972: p. 60) emphasises the role of people when he states that a system is a ‘complex grouping of human beings and machines’. Checkland’s view (1972: p. 52; 2001) is that a system is ‘a structured set of objects and/or attributes together with the relationships between them’. Systems and their properties are examined in greater detail as part of the ‘soft systems methodology’ described by Checkland and Poulter (2006: p. 7).

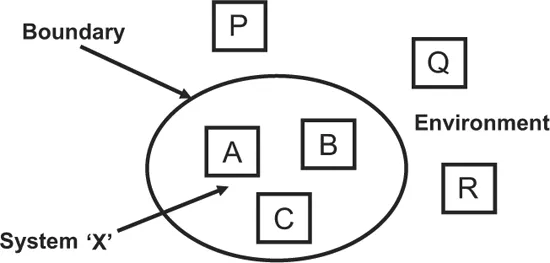

Bearing in mind what has been said above, we1 consider a system to be some part of a physical or abstract universe that has been ‘set aside’ for the purpose of study. Items that make up the identified system are delineated from items that are not within it by means of the system’s boundary. Everything that is not within the system itself is said to constitute the environment in which the system exists. Thus, in Figure 1.1, items A, B and C each form part of the system ‘X’ while objects P, Q and R are not within the system. These latter objects form part of the environment in which the system exists. The line that surrounds the three objects A, B and C is the system boundary.

The environment of a system is important because it can influence both the properties and the behaviour of a system. Similarly, the system itself can have an effect on its environment. The extent to which a system and its environment influence each other will depend upon the ‘permeability’ of the boundary. That is, how easily energy, material or information can pass through it. Depending upon the relative ease with which this can happen, systems can be broadly classified into two basic types: open and closed.

Any given system can usually be visualised in terms of the various sub-systems from which it is composed and the ways in which these interact with each other. In Figure 1.1, for example, the objects labelled A, B and C could be regarded as the three sub-systems that make up the system X. In a motor-car, three of the important sub-systems are: the electrical sub-system, the steering sub-system and the propulsion sub-system. Similarly, in a human being, three examples of sub-systems would be: the digestive system, the respiratory system and the cognitive system.

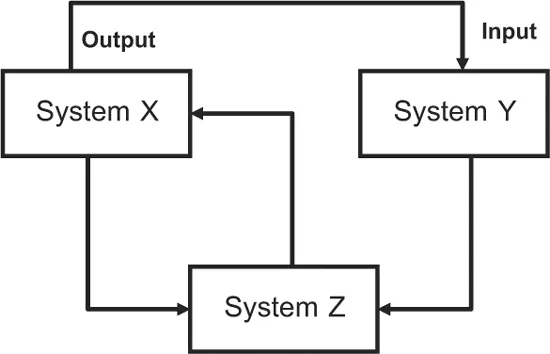

Different systems (and sub-systems within a given system) will normally interact with each other by means of the sets of inputs and outputs associated with them. In Figure 1.2, the three systems X, Y and Z influence each other’s behaviour by means of the input and output channels that interconnect them. One of the outputs from system X appears as an input to system Y; X can therefore influence the behaviour of Y. Both X and Y can influence the behaviour of system Z. System Z can influence X but cannot influence Y nor can Y directly influence the behaviour of system X.

In a human-computer system, for example, the human component can influence the computer by using its keyboard and its mouse – sometimes speech interaction is also possible. Similarly, the computer component can influence its human user by means of its visual display unit and the various audio effects that it can produce. Special forms of tactile interaction are also possible.

Figure 1.1 A system, its boundary and its environment

Figure 1.2 System interaction through input/output channels

At any given instant in time, a system will exist in a particular state. A system could change its state (and hence its behaviour) as a result of interaction with other systems or as a result of internal events that take place within its internal sub-systems. For example, a computer could influence its user’s state of knowledge as a result of material displayed on its screen. Similarly, the type of action a computer performs could be influenced by what a user types at his/her keyboard.

Systems are an important concept which we will use quite extensively in subsequent parts of this book. We will be particularly concerned with the design and development of Electronic Performance Support Systems. Such systems – often referred to by the acronym ‘EPSS’ – are computer-based systems that are intended to improve the performance of human beings within some particular task domain. An EPSS is an example of a human-activity system. The origin and nature of human-activity systems are briefly discussed in the following section.

Human-Activity Systems

Bearing in mind that ‘everything is a system’, there is obviously a very large number of systems in existence. It is therefore very important to have a mechanism by which systems can be classified into different types. Again, Peter Checkland comes to our aid (1972; 2001). He proposed a taxonomy containing five basic types of system: natural systems, designed physical systems, designed abstract systems, human-activity systems and transcendental systems. The latter category refers to systems that are beyond our current state of knowledge – systems that do not currently exist but will exist in the future. Within the context of this book, the most important type of system is the human-activity system.

A human-activity system is defined as one that involves an individual (or a group of people) participating in some form of activity. Most human activity can be interpreted in terms of goal-seeking or problem-solving behaviour. Naturally, individual people undertake a wide range of activities – some are quite trivial while others are more complex. For example, an individual can think, sing and walk (or run) from one location to another. These are referred to as individual activities. In many situations there is a requirement for a group of people to undertake an activity in a collaborative way – thereby functioning as a team. Typical examples of collaborative activity involving a team of people are: a game of football, an army defending (or invading) a country, a surgical team conducting an operation in a hospital and a management team within a company or organisation.

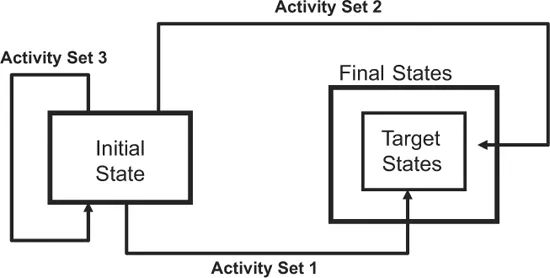

The importance of activity in human goal seeking and/or problem solving is illustrated schematically in Figure 1.3 which shows how a set of activities can lead a system from some initial state towards a (possibly different) final state.

In Figure 1.3, the initial state is the state that our system exists in before we undertake any activities. The target state is the state we want our system to be in after we have undertaken a set of activities that (we hope) will transform the system into its new target state. Three sets of activities are depicted in Figure 1.3. The first of these (Activity Set 1) leads to a target state that we are trying to achieve. The second activity chain leads to a final state that is not the target that we are trying to achieve while the third activity set has no effect in moving the system out of its initial state.

As was mentioned above, there are many different types of activity. There is a need therefore to have a method of classifying these. One useful approach, from the perspective of this book, is to divide activities into two broad categories: aided and unaided. These terms are defined and described below.

Figure 1.3 System state transitions achieved through activity chains

UNAIDED ACTIVITY

An unaided activity is one which does not require the use of any other form of tool or support aid to facilitate its completion. Nowadays, there are not many activities that we conduct in an unaided way. Some simple examples are: thinking, speaking, walking and reading. The last of these is an interesting one for two reasons. First, an additional system component is needed – namely, something to read (such as a book or newspaper); second, unaided reading assumes that the person who is doing the reading has ‘good’ eyesight. As people age, their near-vision capability decreases and some form of optical aid is needed to facilitate the reading process – such as spectacles or a magnifying glass. In this situation the reading process has now become an aided activity.

AIDED ACTIVITY

Bearing in mind what has been said above, we can now define an aided activity as one that requires the use of some form of aid, tool or machine in order to complete it satisfactorily. Most of the activities that we now undertake are aided activities. For example, cleaning ones teeth requires the use of a toothbrush – be this of the simple variety or an ‘electric’ one. Writing a letter or an essay requires us to use a pen, a pencil or a computer-based word-processing system. Similarly, it would be totally impossible to make a telephone call without the use of a mobile phone or a conventional telephone handset.

The concept of aided activity is fundamental to subsequent sections of this book. It is important because we shall be concerned with the design of aids (tools and machines) that will help a human operative to improve his/her performance within some activity that he/she has to undertake. However, before such aids can be designed, it is important to understand the nature of the factors that influence and/or inhibit optimal performance within a given task activity. Some of the limitations that we need to consider are briefly introduced in the following section.

Human Limitations

For a variety of different reasons, and to various extents, human beings are constrained by a range of different kinds of limitation. Some of these are innate or ‘inherent’ while others are ‘acquired’. This section discusses the basic nature of human shortcomings and the sources from which they originate. A number of generic shortcomings are identified as a basis for the development of some of the performance aids that are identified and described in later parts of the book.

INHERENT LIMITATIONS

An inherent limitation is one that originates either from some natural cause or arises as a result of a disability that a person may be born with. For example, the distance that an individual can reach with his/her arm (a roughly spherical or cardiod ‘touch space’ of about three feet in diameter) is a natural innate limitation. Of course, the extent of a person’s reach will depend upon the length of that individual’s arm when it is fully extended. Naturally, the exact shape of the touch space will vary from one person to another – thereby allowing a range of reach possibilities. An individual’s reach limit could be extended by the design of appropriate ‘reaching tools’.

Another important source of inherent limitation is that derived from the numerous types of disability from which people may suffer from birth. Thus, people who are born blind, for example, have a very distinct visual limitation compared with those that are born with ‘normal’ vision.

ACQUIRED LIMITATIONS

Limitations arising from disability can also be ‘acquired’ as a result of some form of accident or as a result of the natural aging processes. For example, a person who is involved in an accident that subsequently necessitates the amputation of a limb will suffer from quite severe limitations in comparison to what he/she was capable of before the accident. In this type of situation, support aids can be designed to compensate for the loss of the limb but these may require the acquisition of new skills.

THE AGING PROCESS

As people grow older, significant changes can take place in their bodies. These changes will, quite naturally, influence what they are able to do and achieve in later life. Therefore, as people with perfectly ‘normal’ health profiles grow older, they will begin to develop age-related (acquired) disabilities. Two of the most obvious changes that people notice as they grow older are the deficiencies that arise in their visual and aural systems. Of course, these degradations can be compensated for and corrected by means of appropriately designed ‘performance interventions’ – spectacles and hearing aids, respectively.

DISABILITY

There is a tremendous range of both physical and mental disability2 that can afflict the human species. Needless to say, a considerable amount of research has been undertaken in relation to the design and fabrication of performance support aids that allow different types of disability to be overcome or, at least, coped with. With many types of disability, the use of an appropriate performance intervention can restore the victim of disability to ‘near normal’ health again. In lots of other situations, such interventions may not restore full ‘normality’ but can be used successfully in order to improve the sufferer’s ability to cope with his/her predicament.

HUMAN LIMITATIONS – SOME EXAMPLES

In order to demonstrate the existence of innate limitations, four simple examples will be used. These will illustrate the natural limits that are placed upon our ability to do things – and how these limits can be overcome through appropriate aids and tools.

Example 1: Ambulation

As a person who enjoys walking and running, I have often pondered about people’s limits in terms of the distance and speed with which the unaided human species can ambulate from one location to another. Of course, there will be innate limits on both the maximum speed and distance that can be covered. In order to overcome these physical barriers to movement, performance aids are often used; a scooter, a bicycle, a car, a ship, a train and an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- Foreword

- Prelude

- PART I FOUNDATIONS

- PART II APPLICATIONS

- PART III CONCLUDIN REMARKS

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Electronic Performance Support by Paul van Schaik, Philip Barker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.