![]()

1

Introduction

Since the open door policy and economic reforms commenced in the late 1970s, dramatic and substantial changes have occurred in China. The reforms have turned the country from an agricultural-based, backward, manual and isolated society into a fast-growing, industrial-based economy (Wang and Wang 2006). China today has one of the fastest economic growth rates in the world, averaging around 10 per cent annually over the past 2 decades (Zheng and Lamond 2009; Zhu et al. 2010). It has become the largest contributor to world economic growth since 2007 and the second largest economy in the world, surpassing Japan in 2010 (Fukumoto and Muto 2012). It is foreseen that China will be the world’s largest economy in the next 1 to 2 decades if the rapid growth can be maintained (Fukumoto and Muto 2012). Compared with the growth of the overall world economy, China’s economic development is often regarded as a miracle (Lin et al. 1996; Yeung et al. 2008; Zheng and Lamond 2009). China’s economic reforms have been an unprecedented achievement, prompting some to comment: ‘never has the world seen a major economic power emerge in such a short time span and attain such a weight in the total world economy’ (McNally 2007: 177).

Due to the increasingly competitive global market, the Chinese Government, however, recognises that relying solely on its previous ‘world factory’ developmental model cannot achieve a sustainable prosperous society (Gu 2010; Ministry of Education 2010). In order to build a sustainable and prosperous society, education is regarded as a key tool (Lewin and Hui 1989). The significance of education in the society has been highlighted by the government’s Outline of Education Reform and Development in China, which stresses that ‘a strong nation lies in its education and a strong education system lies in its teachers’ (Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and State Council 1993: 8). Moreover, accompanying its exponential economic growth, China faces a myriad of challenges including regional development disparities, a widening gap between rich and poor, uneven and unfair wealth distribution and a growing dislike of government officials and the rich (The World Bank 2013). These issues, if tackled inappropriately, could result in social unrest and turmoil (Han 2008; The World Bank 2013). To address these challenges, the provision of quality and equitable education has been deemed critical (Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and State Council 1993; Han 2008). Accordingly, developing education has been a priority at various levels of governments (State Council 2005, 2006). The need to build a highly qualified teaching workforce has been highlighted and reforms to teacher management have been undertaken (Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party 1985).

Traditionally, Chinese people have been highly appreciative of the role of education in their personal development, which was often viewed as the only way to improve one’s life and opportunities. This tradition was strengthened by the introduction of the One-Child Policy that took effect in the late 1970s. Parents now have ambitious expectations for their only child and are often willing to sacrifice whatever they can afford to give their child the best opportunities and educational success (Romanowski 2006). Thus, educational expenses comprise an ever-increasing proportion of income expenditure for households (Zhu et al. 2010). For example, the typical parent in most cities spends at least one-third of their household income on their children’s education, and, in some cities, the proportion can account for up to half of the household income (Mok et al. 2009). With China’s admission to the World Trade Organization in 2001 and the further opening of the Chinese market, the Chinese education sector has been, and will continue to be, an attractive business proposition for international educational organisations in the near future.

The education sector in China is the largest globally (Forrester et al. 2006; Robinson and Yi 2008), for example, there were 14,589,394 full-time teaching staff in 2013 (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2014). This large number of teaching staff, if managed well, will arguably have a positive influence on the 209,905,483 full time students (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2014) and subsequently would benefit the stability and further development of the country. By contrast, if teachers are not managed well, the whole country could suffer, as demonstrated by the Cultural Revolution Movement (for details of the destructive impact of the Cultural Revolution Movement, see chapter 2). As China now stands at a crossroads (Zhang and Chen 2012; Lane 2013), improved teacher management is particularly critical and urgent.

Research gaps, theoretical foundations and key questions

Despite the significance of education, human resource management (HRM) research in this sector has been largely neglected (Ouchi et al. 2005; Cooke 2009; Pil and Leana 2009). Research on HRM is often conducted in industry, particularly in the manufacturing industry (Batt 2002; Sun et al. 2007; Liao et al. 2009), where it has improved our general understanding of the various HRM practices and the relationship between people management and performance. Nevertheless, the features of schools are considerably different from the characteristics of the manufacturing sector and the profit-driven service sector (Cochran-Smith and Fries 2001; Berry 2004). Consequently, the management approaches generated from other sectors might not be directly applicable to the education sector. The lack of HRM research in the public sector in China, for example, in the education sector, has resulted in ‘a significant gap in our understanding of the key changes to, and challenges facing, human resource management in the country as a whole’ (Cooke 2009: 18).

Furthermore, most HRM studies investigating transitional HRM in China only ‘offer general descriptions without showing the nature of current Chinese HRM’ and have ‘failed to explore how and why these changes happened’ (Zhu et al. 2012: 3965). Details of these studies are provided in appendix 1. Adopting the approach of Benson and Zhu (1999), transitional HRM in this study is defined as the process of the transformation and development of HRM practices in response to the changing institutional contexts. Exploring contextual factors in HRM research is important, as they play a significant role in shaping the transformation of HRM (Warner and Rowley 2011). While investigating contextual factors, ‘more sophisticated analytical tools to fully understand specifically how and precisely why HRM has evolved to the particular forms we find it in today’ are called for (Warner 2009: 2183). Institutional theory achieves this goal by conceptualising the complex process of social changes (Warner et al. 2005) and by providing a framework to comprehend radical changes in response to contextual influences (Greenwood and Hinings 1996). Consequently, this study addresses this gap by utilising institutional theory to investigate the influences of contextual factors on HRM.

In addition, even though the significant role of HRM for organisational effectiveness has been noted (Huselid 1995; Kehoe and Wright 2013), this relationship has recently been challenged (Wall and Wood 2005; Wright et al. 2005; Paauwe 2009). It is suggested that the HRM–performance link ‘should be treated with caution’ (Wall and Wood 2005). One reason for this ambiguous link is that the common organisational performance indicators, such as financial results, are also influenced by factors other than HRM issues (Orlitzky et al. 2003; Paauwe 2009). As a result, to understand better the HRM–performance link, better performance indicators are called for (Richard et al. 2009; Guest 2011). We argue that the education sector is an excellent place to test the HRM–performance relationship given that the education sector has a more direct relationship between employees and organisational effectiveness.

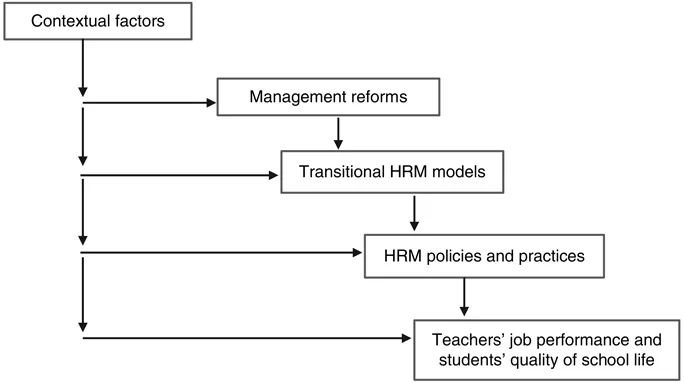

To overcome these deficiencies, this study is designed to explore the contextual factors shaping HRM policy and practice, to identify the current HRM practices, to test a conceptual model that relates HRM to teachers’ job performance and students’ quality of school life, and to examine the transitional HRM model in Chinese schools. Specifically, this study has four aims:

- 1. To explore the contextual factors shaping HRM policies and practices. Past research has shown that contextual factors play a significant role in the transformation of HRM in a radical transitional period, for example, Tsui et al. (2004), Zhu et al. (2007, 2012) and Warner (2011). This aim is addressed by the research question: How have contextual factors shaped HRM policies and practices?

- 2. To explore transitional HRM models in Chinese schools. This aim furthers our understanding of HRM transformation in a transitional economy. Previous research has shown a convergence and divergence between traditional and Western people management models. For example, Benson and Zhu (1999) identified three paradigms of people management in transition: minimalist, transitional and innovative. Ding et al. (2001) identified a transitional convergent model moving further from personnel management to Western HRM with fewer Chinese characteristics. Zhu et al. (2012) presented paternalistic, transactional and differentiated models, while Zhu et al. (2007) in an earlier study identified a hybrid model that had both Chinese and Western elements. This study investigates whether Chinese schools are adopting a hybrid people management model. This aim is addressed by the research question: How can the current HRM system in Chinese schools be best characterised?

- 3. To identify current HRM practices, specifically, recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal and reward management. These four HRM functions represent the most explored issues in the literature (Boselie et al. 2005) and reflect the main objectives of key strategic HRM programmes (Paauwe 2009). Focusing on these functions can answer the call from Cooke (2009) for a more in-depth understanding of the particular aspects of HRM practices. Accordingly, the research question underpinning this goal is as follows: How is HRM conducted in terms of recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal and reward management?

- 4. To test a conceptual model that links HRM to teachers’ job performance and students’ quality of school life. This goal contributes to our understanding of the HRM–performance link that is still uncertain in the literature. This goal is addressed by the research question: Does the adoption of a strategic HRM approach lead to higher levels of teachers’ job performance and students’ quality of school life?

Figure 1.1 Research framework

In summary, this study is conceptualised by the research framework presented in Figure 1.1. First, it identifies the contextual factors and their impacts on management reforms and then it explores the influence of both the contextual factors and management reforms on the transformation of HRM practices. The transitional HRM model in the Chinese school system is subsequently presented and discussed. The focus then shifts to the investigation of HRM policies and practices in the school system through case study analysis. Finally, the impact of the HRM model on teachers’ job performance and their students’ quality of school life is subsequently examined. By doing so, this study will make a significant theoretical and practical contribution to Chinese educational management and the wider HRM literature.

Summary of research methods

The research was conducted in three administrative districts (districts 1, 2 and 3) in Guangdong province. As one of the few regions that have received large shares of capital inflow and investment, Guangdong province is one of the most developed areas in China (Zhu et al. 2010). Among the most developed areas in Guangdong province, districts 1, 2 and 3 have played a significant role in undertaking educational experimentation that, if shown to be successful, will spread to other parts of the country. These districts represent the latest developments in teacher management in the country. A profile of these three research sites is provided in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 A profile of the research sites

| Characteristics | District 1 | District 2 | District 3 |

|

| Area (km2) | 154.7 | 1073.8 | 806.1 |

| Number of subordinate towns | 4 | 8 | 10 |

| Population | 1,100,000 | 2,600,000 | 2,460,000 |

| Number of kindergartens | 126 | 301 | 281 |

| Number of kindergarten students | 35,236 | 61,506 | 58,323 |

| Number of kindergarten teachers | 4,819 | 5,040 | 4,765 |

| Number of PJM schools | 86 | 175 | 194 |

| Number of PJM school students | 111,798 | 223,108 | 223,568 |

| Number of PJM school teachers | 5,535 | 9,962 | 10,237 |

| Number of SMV schoo... |