![]() Part I

Part I

Social order, body order![]()

1 The body in social space

Is the skin the wall enclosing the true self? Is it the skull or the rib- cage? Where and what is the barrier which separates the human inner self from everything outside, where and what the substance it contains? It is difficult to say, for inside the skull we find only the brain, inside the rib-cage only the heart and vitals. Is this really the core of individuality, the real self, with an existence apart from the world outside and thus apart from ‘society’ too?

(Elias, 1978: 24)

When it comes to studying the social world, there are few things that presents themselves with a more spontaneous sense of singularity than the human body. Self- contained, isolated, distinguished by a visible and tangible boundary that separates the “Individual”, the “Subjective” and the “Personal” from its “Environment”, “Society” and “Others”, the body provides the natural template for any type of autonomous, self-regulating system. This is not only true for the natural and the life sciences, but equally applies to the social sciences where, from Hobbes’ ‘Leviathan’ to Luhmann’s ‘systems theory’, the body has served as ‘the prototypical entity of modern social thought’ (Abbott, 1995: 860). An entity that, furthermore, constitutes the sole mode through which social agents present themselves as “individuals”, occupying a discrete and singular position in time and space and endowed with physical, visible features that define each and every one of them as indisputably “unique”. This spontaneous perception of the individual (body) as a self-sufficient unit harbouring a singular and irreducible essence, the ‘homo clausus’ as described by Norbert Elias’ (1978) in the opening quote, is further reinforced by a host of social conventions that not only ratify (often legally), but sanctify this singularity and effectively transform the body into a Durkheimian ‘sacred object’. Conventions which dictate, for instance, that one can only offer one’s body to others, partly or wholly, within social relationships that have been purged of economic or other “profane” interests, as when one “donates” (never “sells”) one’s blood or organs in a purely altruistic gesture or gives one’s body to another in a sexual act that is deemed to be the ultimate expression of love and commitment (and hence fully opposed to the fleeting, interchangeable exchanges of the “market”). Conventions which also clearly define the legitimate manner and circumstances in which the body’s sacred boundary can be transgressed, as shown by the highly revealing example of the gynaecological exam, so skilfully dissected by Henslin and Biggs (2007 [1993]), in which male physicians’ contact to female sexual organs is subjected to a highly ritualized act of ‘depersonification and repersonification’ which, in order to safeguard the sacred character of female sexuality, transforms female patients from subjects (patient-as-person) into objects (patient-as-pelvis) back into subjects.

'Analysis situs'

This self- evidence of the isolated body is in fact one of the most powerful obstacles to sociological objectification. First, because it provides the seemingly most solid basis for the personalist belief in the irreducible uniqueness of each individual. In fact, those who tend to equate sociology with the sinister quest for “iron laws” and immutable “determinisms” and are hence quick to denounce its truths as affronts to human dignity and freedom, only have to invoke the blatantly obvious fact of the morphological singularity of each individual (body) to demonstrate the futility of any attempts at classification or generalization. Secondly, it forms the foundation of a realist or substantialist vision of social reality, which only tends to consider as real or relevant that which it can see or touch. The relational vision of social reality, which always runs up against the fact that this reality tends to present itself in a “thing- like” fashion – in the form of discrete individuals, groups, classes, institutions, etc. – is therefore perhaps nowhere as difficult to apply as when it comes to the sociology of the body. This relational vision in fact hinges on the counterintuitive proposition, that in order to adequately grasp the social logic that shapes bodies in their apparently most singular and spontaneous of features, one needs to move beyond their (all too) visible and tangible reality to construct the system or network of relationships – the ‘figuration’ in Elias’ terms – in and through which they are formed and from which they derive their most distinctive and distinguished properties.

It is in fact Norbert Elias who can be credited for being one of the first to not only demonstrate the full sociological significance of such apparently trivial or vulgar uses of the body as eating with a fork or blowing one’s nose, but for doing so within a properly relational conception of social structure and historical process (and this, one should add, long before either ‘embodiment’ or ‘relationality’ became particularly glossy terms in the sociological lexicon). His seminal The Civilizing Process (2000 [1939]) does not only provide a comprehensive genealogy of changes in Western attitudes towards the body and bodily processes – like eating, drinking, spitting, urinating or defecating – tracing their evolution from relatively unproblematic aspects of everyday life to areas of existence that became increasingly subjected to social taboos, but it explicitly ties such changes to more encompassing transformations in the social fabric of Western societies. Crucially, he located the dynamics of such change not in the mechanical determinations of the “environment” (be it in the form of an economic “infrastructure” or a cultural “Zeitgeist”), nor in the atomized actions of individual agents. Instead, he situated them in the changing pattern of relationships or ‘figurations’ in which these agents or groups of agents find themselves enmeshed. As Elias himself puts it: ‘The “circumstances” which change are not something which comes upon men from “outside”: they are the relationships between people themselves’ (2000: 402).

With the aid a formidable synthesis of a Weberian perspective on state-formation, a Durkheimian take on the division of labour and Freud’s work on the structure of the psyche, Elias retraces the long-term process whereby an agglomeration of small, self- contained ‘survival units’ (Elias, 2000) developed into the complex web of interdependencies that characterize modern societies. These interdependencies not only locked more and more social groups together in chains of mutual dependence – themselves defined by shifting balances of power – but also served as the conduits which facilitated the ‘impregnation of broader strata by behavioural forms and drive- controls originating in court- society’ (Elias, 2000: 427). Propelled by the incessant dynamic of distinction and pretension, forms of bodily control and self-censorship that were originally developed within the tight- knit figuration of the courtly aristocracy gradually spread, first to an ascending bourgeoisie eager to adopt these forms of ‘civilized’ conduct and from there to ever- wider branches of Western social figurations. While Elias’ work hence provides valuable insights for sociologists of the body, the biggest strength of his approach – i.e. its focus on the historicity of the body as the product of long- term social developments – might also be its greatest drawback. In fact, the keen sense for the often subtle social differences in comportment and etiquette that informs his historical analyses – like his skilful dissection of the mannerisms and power- dynamics at the court of Louis XIV (Elias, 1983) – often stands in shrill contrast to the rather offhand manner in which he brushes over contemporary social differences in bodily self- control. While he is by no means oblivious to such differences, the focus on the long- term perspective often leads him to downplay their significance.1 When read through the lens of the past, contemporary contrasts in “civilized” behaviour will undeniably appear as less sharp and extreme as those of previous generations:

Seen at close quarters, where only a small segment of [the civilizing process] is visible, the differences in social personality- structure between the upper and lower classes in the Western world today may still seem considerable. But if the whole sweep of the movement over centuries is perceived, one can see that the sharp contrasts between the behaviour of different social groups – like the contrasts and sudden switches within the behaviour of individuals – are steadily diminishing.

(Elias, 2000: 383)

Elsewhere he writes:

The pattern of self-constraints, the template by which drives are moulded, certainly varies widely according to the function and position of the individual within this network, and there are even today in different sectors of the Western world variations of intensity and stability in the apparatus of self-constraint that seem at face value very large.

(Elias, 2000: 369, my emphasis)

However, he then rushes to add:

But when compared to the psychological make- up of people in less complex societies, these differences and degrees within more complex societies become less significant, and the main line of transformation, which is the primary concern of this study, emerges very clearly.

(Elias, 2000: 369)

Elias is in fact quite insistent that the gradual diminishing of class- contrasts in civilized comportment is not a matter of analytical perspective alone. In fact, he takes it to be ‘one of the most important peculiarities of the “civilizing process” ’ (2000: 383) that the dynamic of functional differentiation, which ties dominant and dominated groups into ever-tighter webs of interdependence, produces a gradual attenuation of differences in their comportment. If dominated groups aim to emulate and adopt elements of the lifestyle of dominant groups, it is equally true that the latter increasingly assimilate forms of behaviour of those who occupy dominated positions within the figuration. Hence, inasmuch as contemporary ‘differences and gradations in the conduct of lower, middle- and upper- classes’ are still considered important, Elias relegates them to a ‘set of problems of their own’ (ein Problemkreis für sich) which he leaves it to others to tackle.2 However, as indicated in the introduction, it is precisely these ‘differences and gradations’ that form the subject of our particular inquiry. What we therefore need is an analytical perspective that shares Elias’ insistence on the primacy of relationships in the study of social phenomena, but is at the same time more attuned to the role of contemporary class- divisions in shaping the everyday uses of the body. In this chapter, I will aim to show that such an approach can be found in the work of an author who developed a sociological perspective that is highly similar to that of Elias and is in some ways indebted to it, namely Pierre Bourdieu.

An 'order of coexistence'

The ‘subterranean affinities’ (Paulle et al., 2012) between the sociologies of Elias and Bourdieu are manifold and in themselves worthy of more attention than they have thus far received. At the most general level, their work has produced a number of conceptual tools (habitus, field, figuration) that deliberately aim to transcend some of the cardinal oppositions that continue to haunt modern social thought (individual/society, micro/macro, mind/body, conflict/consensus, structure/agency, etc.). The expression ‘tools’ is moreover not chosen lightly, since their concepts did not arise out of a purely theoretical synthesis of a selective body of canonical authors (in the vein of Parsons’ ‘structural functionalism’ or Giddens’ ‘structuration theory’) but were crafted in and for the confrontation with a particularly broad array of empirical objects. More substantially, their respective brands of sociology are animated by a highly similar social ontology. Like Elias, Bourdieu treats social agents as fundamentally characterized by a ‘double historicity’. According to this view, each individual agent is at once the product of a collective history (fylogenesis or sociogenesis), defined as the totality of manners of seeing, acting, feeling, etc. that have emerged from the historical struggles of past generations, which is in turn acquired, either partly or wholly, within the particular course of an individual, social trajectory (ontogenesis or psychogenesis). It is this doubly historical conception of the social agent that also informs their mutual interest in the relationship between social and mental structures, that is, in the homologies between the structural organization of social systems and the cognitive schemata of those who constitute such systems. This is no doubt one of the main reasons for their mutual appropriation of the concept of ‘habitus’, even though Elias tends to develop the notion more strongly along the lines of an historicized psychoanalysis of affective regulation and libidinal sublimation, while Bourdieu tends to continue in the Durkheimian tradition and its interest in the problem of ‘primitive classifications’. Finally, and more relevant for the case at hand, Bourdieu’s sociology is similarly rooted in a thoroughly relational vision of social reality.3 In fact, he proposes to treat sociology as a ‘social topology’ (Bourdieu, 1985: 723; Bourdieu, 1989: 16; Bourdieu, 1996). This topological perspective is rooted in the methodological principle that the analyst, before plunging head over heels into the particularities of a specific object, should first attempt to construct (within the limits of the available data) the system of relationships in which this object is entangled and from which it derives its particular characteristics. These relationships are themselves irreducible to the fleeting conjunctures of face- to-face interaction, but instead take the form of objective power- relationships (of the type professor/student, employer/employee, man/ woman, etc.) which ‘possess a reality existing outside individuals who, at every moment, conform to them’ (Durkheim, 2013: 44) and hence effectively structure and constrain the manner in which their concrete interactions unfold.

As such, they form a particular configuration of social positions that are linked to another ‘through relations of proximity, vicinity or distance, as well as through order relations, such as above, below and between’ (Bourdieu, 1996: 11). Together, this system of relative positions constitutes what Bourdieu coins a ‘field’ which, when referring to the social order in its entirety, he specifies as the ‘field of social classes’ or more generally as ‘social space’ (Bourdieu, 1984: 228). The principal forces that structure this space and determine the relative position of agents or groups of agents within it are the different types of social power or ‘capital’. Taking his cues from Weber’s (1978 [1921]: 302ff. and 926ff.) multidimensional view of social status, as expressed in his conceptual trinity of ‘Klasse’, ‘Stand’ and ‘Partei’, Bourdieu distinguishes between three basic forms of social power, namely economic, cultural (or informational) and social capital. To these three basic forms, which are themselves further differentiated according to the particular type of field (scientific, literary, . . .), Bourdieu adds a fourth type, namely symbolic capital, which is the particular form that each type of capital takes when it is perceived and recognized as “legitimate” and as such ceases to exist as “capital”, namely as accumulated social labour, but instead comes to function as a sign of innate, natural quality such as “class”, “success”, “intelligence”, “talent” or “charm”.

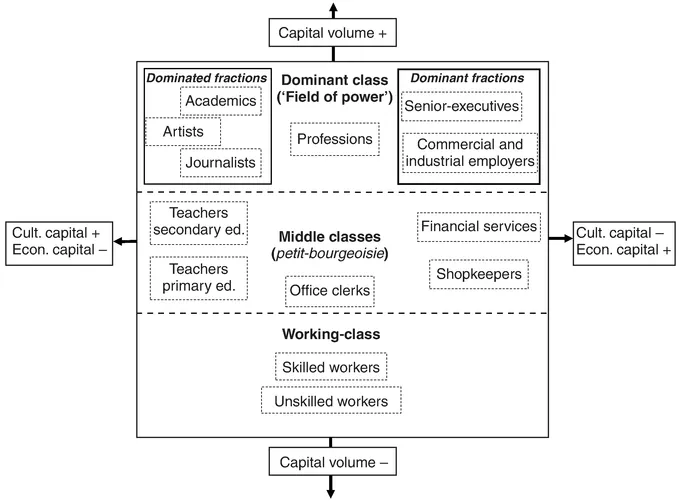

Figure 1.1 Diagram of social space.

Using these different forms of capital, it becomes possible to situate agents within a multi-dimensional space (see Figure 1.1). The first, and most important dimension of this space discriminates between social agents on the basis of their overall ‘capital-volume’ or the totality of resources that determine their relative degree of power in and over the space. On the basis of such differences in total volume, Bourdieu distinguishes between three ‘major classes of conditions of existence’ (1984: 114). Those who are situated at the top of the space, the dominant class (or the ‘field of power’), are most well-endowed with the different types of profitable resources and are as such furthest removed – objectively and subjectively – from those who occupy positions at the bottom of the space, the working or popular classes, who tend to be most deprived in this respect. Between these two extremes, Bourdieu situates an intermediate social category, the middle- class or p...