- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

This book is the first study to consider the extraordinary manuscript now known as the Carrara Herbal (British Library, Egerton 2020) within the complex network of medical, artistic and intellectual traditions from which it emerged. The manuscript contains an illustrated, vernacular copy of the thirteenth-century pharmacopeia by Ibn Sar?b?, an Arabic-speaking Christian physician working in al-Andalus known in the West as Serapion the Younger. By 1290, Serapion's treatise was available in Latin translation and circulated widely in medical schools across the Italian peninsula.

Commissioned in the late fourteenth century by the prince of Padua, Francesco II 'il Novello' da Carrara (r. 1390–1405), the Carrara Herbal attests to the growing presence of Arabic medicine both inside and outside of the University. Its contents speak to the Carrara family's historic role as patrons and protectors of the Studium, yet its form – a luxury book in Paduan dialect adorned with family heraldry and stylistically diverse representations of plants – locates it in court culture. In particular, the manuscript's form connects Serapion's treatise to patterns of book collection and rhetorics of self-making encouraged by humanists and practiced by Francesco's ancestors.

Beginning with Petrarch (1304–74) and continuing with Pier Paolo Vergerio (ca. 1369–1444), humanists held privileged positions in the Carrara court, and humanist culture vied with the University's successes for leading roles in Carrara self-promotion. With the other illustrated books in the prince's collection, the Herbal negotiated these traditional arenas of family patronage and brought them into confluence, promoting Francesco as an ideal 'physician prince' capable of ensuring the moral and physical health of Padua. Considered in this way, the Carrara Herbal is the product of an intersection between the Pan-Mediterranean transmission of medical knowledge and the rise of humanism in the Italian courts, an intersection typically attributed to the later Renaissance.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

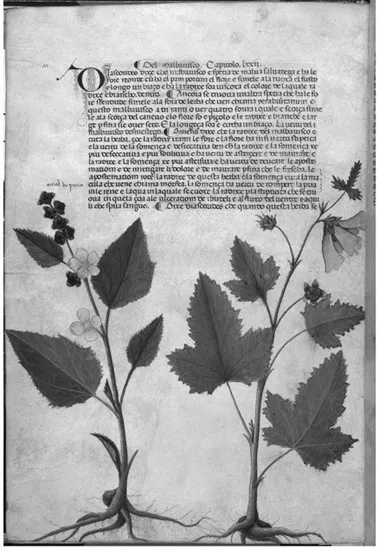

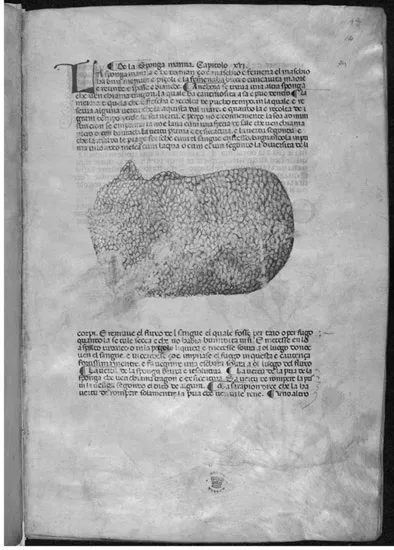

The Carrara Herbal and the traditions of illustrated books of materia medica

Botanical illustration in the Carrara Herbal

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Medicine and metaphor at the Carrara court

- 1 The Carrara Herbal and the traditions of illustrated books of materia medica

- 2 The healthy pleasures of reading the Carrara Herbal

- 3 The ‘physician prince’ and his book

- 4 Portraits of the Carrara

- 5 Physiognomy in late medieval Padua

- 6 Embodiments of virtue in Francesco Novello’s library

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plates