eBook - ePub

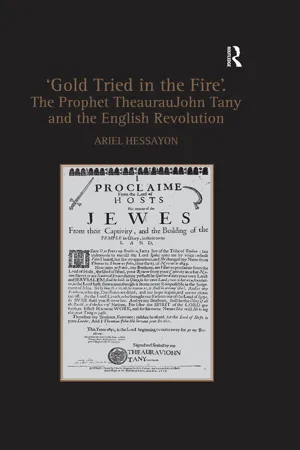

'Gold Tried in the Fire'. The Prophet TheaurauJohn Tany and the English Revolution

- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

'Gold Tried in the Fire'. The Prophet TheaurauJohn Tany and the English Revolution

About this book

This is a study of the most fascinating and idiosyncratic of all seventeenth-century figures. Like its famous predecessor The Cheese and The Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller, it explores the everyday life and mental world of an extraordinary yet humble figure. Born in Lincolnshire with a family of Cambridgeshire origins, Thomas Totney (1608-1659) was a London puritan, goldsmith and veteran of the Civil War. In November 1649, after fourteen weeks of self-abasement, fasting and prayer, he experienced a profound spiritual transformation. Taking the prophetic name TheaurauJohn Tany and declaring himself 'a Jew of the Tribe of Reuben' descended from Aaron the High Priest, he set about enacting a millenarian mission to restore the Jews to their own land. Inspired prophetic gestures followed as Tany took to living in a tent, preaching in the parks and fields around London. He gathered a handful of followers and, in the week that Cromwell was offered the crown, infamously burned his bible and attacked Parliament with sword drawn. In the summer of 1656 he set sail from the Kentish coast, perhaps with some disciples in tow, bound for Jerusalem. He found his way to Holland, perhaps there to gather the Jews of Amsterdam. Some three years later, now calling himself Ram Johoram, Tany was reported lost, drowned after taking passage in a ship from Brielle bound for London. During his prophetic phase Tany wrote a number of remarkable but elusive works that are unlike anything else in the English language. His sources were varied, although they seem to have included almanacs, popular prophecies and legal treatises, as well as scriptural and extra-canonical texts, and the writings of the German mystic Jacob Boehme. Indeed, Tany's writings embrace currents of magic and mysticism, alchemy and astrology, numerology and angelology, Neoplatonism and Gnosticism, Hermeticism and Christian Kabbalah - a ferment of ideas that fused in a millenarian yearning for the hoped for

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 'Gold Tried in the Fire'. The Prophet TheaurauJohn Tany and the English Revolution by Ariel Hessayon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Genesis

Chapter 1

Genesis

Nothing that has taken place should be lost to history

[Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History]

[Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History]

His name was Thomas Totney. He was baptized on 21 January 1608 in the parish of South Hykeham, Lincolnshire. He was the third but eldest surviving son of John and Anne Totney. His father John Totney came from the village of Little Shelford, Cambridgeshire.1

Little Shelford, Cambridgeshire: The Totneys

Little Shelford is about six kilometres south of Cambridge, in the deanery of Barton, on the south-west bank of the river Cam. It is very flat, and lies mostly on the Lower Chalk, with a strip of alluvium and valley gravels along the river. Described as ‘fruitfully seated both for corn & Grass’, the village was favoured for hunting and hawking and known for its wholesome air.2 The parish consisted of about 1,200 acres. Within the parish bounds there was a meadow, held in common, and three fields of arable land known by the seventeenth century as Middle field, White field and Danford field. These fields were divided into parcels known by the tenants’ names and by such names as ‘Bragge’ and ‘Angell Harpe’. Much of the land was held as copyhold by local farmers and the main crops grown were barley, saffron and peas. Villagers also kept cows, sheep, horses and pigs. The trees were largely oak, ash, elm, maple and willow. There was a water-mill used for grinding corn (usually wheat) and some inhabitants may have fished in the Cam. A bridge spanned the shallow brook, connecting Little with Great Shelford. Originally made of wood, it was rebuilt in stone by the 1630s. In the 1660s the foundations had become clogged with weeds and flags. This area of the river bank appears to have served as a dump for muck and manure. Unusually, Little Shelford had only one manor. This was held in the eleventh and twelfth centuries by the de Scalers family. In 1231 the manor passed by marriage into the possession of the Freville family. There it remained until 1577 when George Freville and his relations alienated the manor and other parish lands to John Banckes. Banckes proceeded to dismember the manor, alienating land, the water-mill and fishing rights before selling the chief demesne and the manor house to Tobias Palavicino. Palavicino’s manor house was occupied in the early seventeenth century by Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton and was also leased to Thomas Coteele, a London merchant. In 1628 Palavicino sold the manor house and his demesne to John Gill of Northamptonshire for 3,300l. John Banckes’s widow, Priscilla, retained the manor of Little Shelford until 1634. Afterwards, Banckes’s son sold the manor to Daniel Wigmore, Archdeacon of Ely. The old manor house, seat of the Frevilles, was decorated with tapestries in the 1520s and contained a hall, two parlours, a great chamber and several little chambers. Rebuilt by Palavicino in the early seventeenth century in the Italian style as a three-storey brick structure with gabled wings and a large piazza the manor house was accounted a ‘delicate neat’ dwelling.3 The local church was dedicated to All Saints and said to be ‘very great & comely’. It was a stone structure, parts of the nave dating from the twelfth and fifteenth centuries, the chancel from the thirteenth, and the vestry and tower from the early fourteenth.4 Grave covers from the Saxon and post-Conquest period were also worked into the building. On the steeple was a cross. Often in decay the church was in constant need of cleaning and repair. Incorporated in the interior was a south chapel belonging to the lords of the manor. Most likely seating for the parishioners was set, with families having rights to particular pews (whole or in part). Among the church ornaments were a rood-screen, figures of saints in alabaster and a number of stained glass windows. There were also several monuments to the Freville family – images, coats of arms and accompanying inscriptions in the chancel windows, and some sepulchral brasses dating from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. On an altar tomb in an arch of the north wall of the chancel was a stone effigy of Sir John de Freville, a knight of St.John of Jerusalem who died in the reign of Edward II, fully armoured, legs crossed, sword by his side, a lion at his feet, incised lettering above his head. The octagonal stone font was early fourteenth century. In the sixteenth century there was a pair of copper censers and two candlesticks, while the pulpit dated from 1633 and a silver chalice and paten from 1638. Light was provided by torches, lanterns and candles in times of darkness. The living was a rectory, valued at 15l. 9s. 8d. in the reign of Henry VIII, and at 100l. in 1650. The advowson was in the patronage of the lords of the manor. During the sixteenth century several rectors were non-resident, their duties taken over by a curate. In 1615 the rectory had two barns, a hayhouse, a stable, gardens and an orchard. No rectors are known to have been presented for non-residence during this period. In a survey made for the Bishop of Ely in 1563 Little Shelford was listed as having twenty-two households. Though the population could slump in times of dearth and plague (thirty-eight burials were recorded for the old style years 1625 and 1626) it continued to rise steadily: the mean number of baptisms per annum between 1601 (o.s.) and 1627 (o.s.) was 6.85, the mean number of burials 5.48. By the 1660s there were between thirty-five and forty households in the parish. The majority of the inhabitants were tied to the land, but in the early seventeenth century the parish also had a miller, blacksmith, carpenter, tailor and victualler. From the late sixteenth century there was, moreover, a schoolmaster in neighbouring Great Shelford. In the 1660s many villagers lived in two room cottages with no second floor or three roomed dwellings with hall, parlour and service room. Some husbandmen and yeomen had additional service rooms and upper rooms. The contents of these homes reflected wealth and social status. At their deaths some villagers’ possessions amounted to little more than a bed, mattress, pair of sheets, pillow and blanket; others might have a chest, trunk, table and chairs, candlesticks, pewter dishes, brass pots, frying pan, kettle, cheese press, kneading trough, a quern for grinding corn and a stone trough in the yard for the horse. A few literate parishioners may have owned a Bible, and perhaps also other printed material; books (possibly devotional works), pamphlets, chapbooks, almanacs, ballads and the like. The wealthier sort wore fine or course woollen gowns, doublets and jackets over their undergarments; their widows, petticoats and gowns. The clothing of the poor is unrecorded. The church bells – when not broken and ropes were available – were rung on Coronation day and other special occasions. The lives of most of the inhabitants seem to have revolved around the agricultural year and it is likely that a variety of local customs were observed. A villager may have subsisted on a diet of barley bread, butter, cheese (perhaps flavoured with saffron), garden vegetables (possibly cabbage, cauliflower and peas), and meat (most likely bacon). To drink there was beer brewed from barley. Sometimes a parishioner might keep an alehouse. There were, in addition, several inns, notably the ‘White Lion’ in nearby Trumpington and the ‘Katherine Wheel’ on Trumpington Street in Cambridge. Village pastimes included morris dancing, bowls, and football – played now and then on Sundays against neighbouring villages. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the inhabitants of Little Shelford were presented before the church courts. Offences varied. Some failed to receive communion or attend church, others worked on the Sabbath or holy days. There were also a host of sexual misdemeanours: suspected whoredom, incontinent living (fornication, adultery), and begetting or harbouring bastard children.

*

The name Totney comes from the Old English personal name Totta and probably means Totta’s island of land, a piece of dry ground in a fen or marsh.5 Totneys had been living in Little Shelford since at least 1279, though their presence there supposedly dated back to the Norman Conquest. Writing in the 1630s, the Cambridgeshire antiquarian John Layer recorded the survival of a ‘Tradition’. He had been told by the locals of a certain Barnard de Freville, said to have possessed the manor of Little Shelford after the Conquest, who had come into England:

w[i]th W[illia]m the Conqueror, [and] brought w[i]th him one Totney his serv[an]t. Whom they say he made his homager of certain Lands in this Town, & that their Posterities have lived & continued here ever since … only Totney outlived the Frevile a while, & hath left some memory of his Name behind him there w[hi]ch the other has not.6

The name Totney is not recorded in the lists of the companions of William the Conqueror, though the name Freville is – as is the name Tany. Nor does the name Totney occur in the Cambridgeshire section of the Domesday Book. Indeed, of the early members of the Totney family little is known. A John Totney was named in an inquisition of 1325, fined in 1325–26 and assessed for a lay subsidy in 1327.7 A William Totney witnessed a will in 1487 and was named in a deed of 1490. His will was made probate in 1499.8 A Thomas Totney married a woman called Alice, witnessed a will in 1522, and may have been assessed in the subsidy of 1523–24. His will was made probate in 1525 and included the customary offering to the high altar for tithes negligently forgotten as well as gifts to the sepulchre, the guild of ‘Our Lady’s Light’ and a contribution towards the restoration of the church steeple. The scribal formula for bequeathing his soul was after the orthodox Catholic fashion.9 A daughter named Rose Totney was left money by the lady of the manor in 1529.10 A William Totney married a woman named Elizabeth and witnessed wills made in 1537 and 1539. His will was made probate in 1540 and included a donation towards the repair of the church bells. His soul was bequeathed in a manner consonant with orthodox Catholic doctrine.11 A son named John Totney was given two bushels of barley and his father’s coat in 1546. A man of the same name was assessed in the subsidy of 1558.12

It seems likely that the Totneys were modest yeoman farmers. Recorded as tenants of the lord of the manor in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century, they occupied a messuage in the 1620s and held a small amount of copyhold land – some twenty acres of arable and four acres of meadow. This land was probably divided into parcels and lay in Little Shelford and the neighbouring parishes of Hauxton, Harston and Newton.13 The first Totney of whom something substantial is known was John Totney, grandfather of Thomas. John Totney and his wife were presented before the church courts in 1569 for permitting eating and drinking in their alehouse during divine service, a charge most likely indicating their poverty. In 1579 they were presented together with another married couple for failing to receive communion for almost a year. All four were described as malicious and slanderous persons living out of charity, suggesting a neighbourly dispute. Shortly afterwards the contending parties were reconciled before the rector and agreed to receive communion together.14 In the last years of his life John Totney seems to have been well-established within the social hierarchy of the village community. He could sign his own name, witnessed fellow parishioners’ wills, and held the offices of sidesman in 1596 (o.s.) and churchwarden in 1599 (o.s.) and 1602 (o.s.).15 He also hired a cow from year to year belonging to the church, the rent going to benefit the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction: TheaurauJohn Tany and the English Revolution

- Part I: Genesis

- Part II: Genealogy of the High Priest

- Part III: King of the Jews

- Bibliography

- Index

- Index of names

- Index of places

- Index of signs

- Index of canonical and extra-canonica texts