eBook - ePub

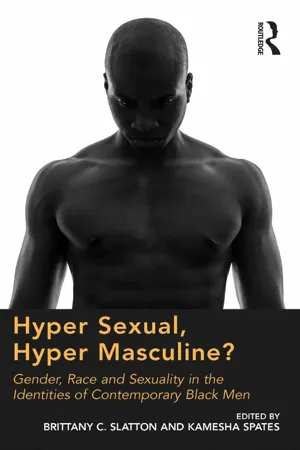

Hyper Sexual, Hyper Masculine?

Gender, Race and Sexuality in the Identities of Contemporary Black Men

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hyper Sexual, Hyper Masculine?

Gender, Race and Sexuality in the Identities of Contemporary Black Men

About this book

This book provides critical insights into the many, often overlooked, challenges and societal issues that face contemporary black men, focusing in particular on the ways in which governing societal expectations result in internal and external constraints on black male identity formation, sexuality and black 'masculine' expression. Presenting new interview and auto-ethnographic data, and drawing on an array of theoretical approaches methodologies, Hyper Sexual, Hyper Masculine? explores the formation of gendered and sexual identity in the lives of black men, shedding light on the manner in which these are affected by class and social structure. It examines the intersecting oppressions of race, gender and class, while acknowledging and discussing the extent to which black men's social lives differ as a result of their varying degrees of cumulative disadvantage. A wide-ranging and empirically grounded exploration of the intersecting roles of race, masculinity, and sexuality on the lives of black men, this volume will appeal to scholars across the social sciences with interests in race and ethnicity, gender and sexuality, social stratification and intersectionality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hyper Sexual, Hyper Masculine? by Brittany C. Slatton, Kamesha Spates, Brittany C. Slatton,Kamesha Spates in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Challenges and Constraints of Masculine and Sexual Identity Formation

Racialized social structures create dehumanizing mythological constructions and stereotype black male masculinity and sexuality. These stereotypes lead to unrealistic societal expectations for black men, constraining or limiting their ability to develop their own sexual and masculine identities. The contributors in this section use various approaches to describe these types of constraints. In Chapter 1 Earl Wright provides an insightful personal narrative, sharing how he learned as a child that real men are not punks, and gays and lesbians cannot be trusted. It was not until he developed a friendship with a gay man that he learned to overcome his own homophobia. Interestingly, this friendship led many people to question the nature of their relationship, and his own sexuality. His experiences reveal the complexity of masculinity and sexuality in the life of a heterosexual male. In the second chapter, Candy Ratliff uses the symbolic interactionist framework to explain the meaning of masculinity and sexuality in the black community. She argues that the myriad descriptions and interpretations of what it means to be a black male can create dissonance in role interpretation, role execution, and identity formation of young African American boys and men. Ultimately, what African American males learn about societal expectations for masculinity influences their self-concept and how they relate to others. This section concludes with Brittany Slatton’s chapter on black masculine identity. She argues that potential for developing a healthy masculine identity is constrained by society’s normative expectations of hypersexuality, hypercriminality, and violence from black men. Laws and policies against crime are applied disproportionately to black men, leading to their mass incarceration. Additionally, expectations of criminality and violence shape police officers, judges, jurors and other individuals’ encounters with black men, which can lead to aggressive overreactions—including excessive surveillance, arrests, and unjustified killings. Slatton posits that the normative expectations of white society limit black men’s options and cause dire consequences for their lives.

Chapter 1

Notes from a Former Homophobe: An Introspective Narrative on the Development of Masculinity of an Urban African American Male

The use of one’s memory to recall events, traumatic or non-traumatic, for qualitative scholarly inquiry is a valuable research tool. Systematic sociological introspection allows a researcher the opportunity to incorporate their personal narrative into a scholarly inquiry that does not correlate with the occurrence of the event examined.1 This technique is found most notably in Carol Rambo’s account of abuse she experienced as a child. It was after becoming an academician that she, through a reconstructed chronology of field notes, drew upon her childhood experiences to provide a detailed and graphic account of sexual and mental abuse at the hands of both her mother and father.2 Rambo’s use of a layered account, the dichotomous incorporation of the frame of both participant and scholar, enhances her inquiry through an understanding and examination of the subject from the simultaneous perspectives of the survivor of a traumatic event as well as that of a trained social scientist examining the impact of child sexual and mental abuse. This inquiry is similar to Rambo’s through the use of systematic sociological introspection and a layered account to frame and analyze past events. The primary objective of this endeavor is to use this personal narrative to assist others in understanding how similarly situated black males can be socialized into their masculinity and manhood. Specifically, this chapter offers an examination of black masculine identity formation within a specific urban poverty level environment and within a highly homophobic culture.

The Fatherless Household

I was born in 1971 and came of age as an adolescent during the presidency of Ronald Reagan and his trickle-down economic theory. While some may have benefitted from this economic philosophy that was grounded in the idea that tax breaks for companies and those in the highest income brackets would lead to prosperity for all Americans, the people living in my poverty tract neighborhood of Hollywood in Memphis, Tennessee were not among that lot. 1983 United States Census data indicate that 35 percent of all black Americans lived below the poverty line. The poverty rate for black female headed households in that year was nearly 60 percent. These are the data that frame the reality of my late childhood and adolescence. My parents divorced when I was two years old. The story that I heard very often as a child, and still occasionally as an adult, is that my mother left my father because she tired of the frequent and brutal beatings at his hand. She often recounts one specific event that convinced her to finally leave. After enduring a brutal beating, and in an attempt to literally save her life, she raised the bathroom window of their duplex and, without any clothes on, jumped out and ran to a friend’s house for safety. Unlike some women, my mother’s salary was the primary source of household income so she was able to support herself and me after the escape even if, by the standards of the federal government, we lived below the poverty line.

My mother worked as a licensed practical nurse (LPN) and attended community college during my adolescence. Her nursing salary was just enough to pay the monthly bills and not much else. There were many nights when we found ourselves eating either cereal with no milk or a single grilled cheese sandwich made with government issued block cheese for dinner. On some nights my mother did not eat dinner. At those moments she would say that she was not hungry or had already eaten. It was only after reflecting on those experiences with her some years later that I learned my mother had not told me the truth and that, in fact, she went to bed hungry on many nights. We had a very supportive extended family that would have cringed and acted upon hearing of our lack of food, however, my mother was a proud woman who always wanted to keep her ‘business’ private—even if that came at the sacrifice of food for her and her only child. On at least one occasion our extended family became aware of our plight. I vividly remember my grandmother coming to our house one day and demanding that we come live with her. Without resistance we left. The visits to my grandparents would generally last a week or two before my mother’s desire to be in her own home kicked in. As we were preparing to leave my grandparent’s home on one occasion I asked my mother if I could stay and live with them, at least during the school week. This seemed like a pretty reasonable idea to me as a child since I was already using my grandparents address to attend school. Instead of my mother waking me at five am to prepare for school, preparing herself for work, then dropping me off at my grandparents home every morning at six am, this new arrangement would benefit us all. My grandparents concerns about my wellbeing would be allayed, my mother would have additional discretionary money to spend and I would be in a home where food was plentiful.

I enjoyed living with my grandparents if for no other reason tha I knew I would have a full meal every night. I also enjoyed living with my grandparents because I was finally in a household that included a male figure. Although my father lived, literally, less than a mile away there was very little contact between us. He had started another family with a second wife and began to have children with her. He made it clear in both word and deed that I had no important or significant role in his life at that time. So, it was my grandfather to whom I looked to see how ‘men do things’ since my family was, and remains, numerically dominated by women. My grandfather was the stereotypical man of the mid-twentieth century who believed men ruled their household with an iron fist and that women and children must ‘know their place.’ I remember one evening we were on our way to a local restaurant for a chicken dinner as we did every Friday night. Along the way we saw a two-car accident and I exclaimed, ‘golly!’ Before I knew it I had been slapped in the mouth. Some years later I theorized that he thought I was too close to saying ‘god damn’ and, being the God fearing man that he was, believed his strike was against my future use of profanity. However, as I sobbed quietly in the backseat of the car I perceived his strike as yet another example of his iron fist. The last and most prominent memory of my grandfather’s iron fist is of an argument he had with my grandmother. While I do not remember the specific cause of his discontent, I do recall that he was displeased with something she had done. My grandmother made several attempts to please him and diffuse the situation, possibly because she was aware that I could see them both through the bedroom door that was adjacent to the dining room where the ‘conversation’ was taking place. Despite her attempts to correct her mistake, even if she had not made one, he continued to curse and rage. All of a sudden I heard a loud slap and corresponding thud. Because their conversation had moved from the dining room to the kitchen I did not see my grandfather hit my grandmother. But there are some things that even a child need not see with their eyes to understand intuitively. Shortly after this event I succeeded in getting my mother’s and grandmother’s approval to allow me to live with my grandmother’s sister.

‘You Either Fight that Boy Down the Street or You Fight Me!’

While I enjoyed living with my grandparents, I enjoyed being at my aunt’s even more. My aunt was one of the first people in our neighborhood to have cable television, including the x-rated channels that I fought my sleep to stay up to watch on many nights. Plus, she always had a bottle of liquor below the sink that was available at my adolescent whim. Although my aunt and grandparents houses were separated by about seven homes on the same street, my aunt’s home seemed many miles away. Not only could I escape hunger, chaos and the occasional episode of domestic violence experienced at my mother’s and grandmother’s home, I was enthralled at being treated as if I were the most special child in the world by my aunt and cousins. Consistent with my life prior to this point, I had no positive male role model. After I moved in with my aunt this void was filled by two older female cousins. My aunt provided for the household through her job as a seamstress and my two cousins were charged with the daily task of caring for me. One cousin was very involved in sports and we would sit for hours and watch football. The house would become tense with excitement every time her Dallas Cowboys and my Pittsburgh Steelers played. Bragging rights were at stake and we both wanted them badly. My other cousin kept me focused on schoolwork, and on one memorable day walked me back to school for an intense teacher’s conference after I brought home a report card with failing grades. Finally, I felt a sense of calm and peace. I had a home where I could engage in normal activities as a child in a two-parent family environment. The only allowance is that the father role in my household was performed primarily by two young women who were only slightly older than me.

I gravitated to sports at an early age. Tackle football was the sport of choice in my neighborhood and I quickly became known as someone who was fearless and would do anything to catch the football. At the age of ten I was playing tackle football in the community with guys who played on the local high school team. Throughout my neighborhood in general, and through playing football specifically, there was always an emphasis on being tough and being...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Blackness, Maleness, and Sexuality as Interwoven Identities: Toward an Understanding of Contemporary Black Male Identity Formation

- Part I Challenges and Constraints of Masculine and Sexual Identity Formation

- Part II Negotiating Unequal Ground

- Part III Critical Interpretations of Black Men and Genderism

- Part IV Black Men’s Counter-narratives in the Struggle for Masculine and Sexual autonomy

- Index