eBook - ePub

Public Religion and the Politics of Homosexuality in Africa

- 278 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Public Religion and the Politics of Homosexuality in Africa

About this book

Issues of same-sex relationships and gay and lesbian rights are the subject of public and political controversy in many African societies today. Frequently, these controversies receive widespread attention both locally and globally, such as with the Anti-Homosexuality Bill in Uganda. In the international media, these cases tend to be presented as revealing a deeply-rooted homophobia in Africa fuelled by religious and cultural traditions. But so far little energy is expended in understanding these controversies in all their complexity and the critical role religion plays in them. This is the first book with multidisciplinary perspectives on religion and homosexuality in Africa. It presents case studies from across the continent, from Egypt to Zimbabwe and from Senegal to Kenya, and covers religious traditions such as Islam, Christianity and Rastafarianism. The contributors explore the role of religion in the politicisation of homosexuality, investigate local and global mobilisations of power, critically examine dominant religious discourses, and highlight the emergence of counter-discourses. Hence they reveal the crucial yet ambivalent public role of religion in matters of sexuality, social justice and human rights in contemporary Africa.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Public Religion and the Politics of Homosexuality in Africa by Adriaan van Klinken, Ezra Chitando, Adriaan van Klinken,Ezra Chitando in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I The politicisation of homosexuality

1 ‘For god and for my country’ Pentecostal-Charismatic churches and the framing of a new political discourse in Uganda

Barbara Bompani1

DOI: 10.4324/9781315602974-2

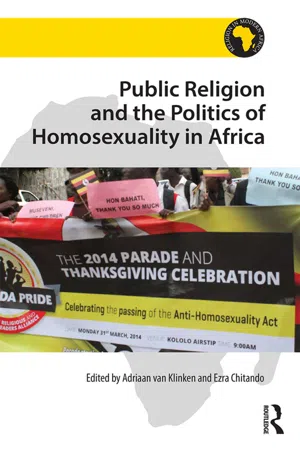

On Monday 31 March 2014 30,000 Ugandans gathered at Kololo stadium in Kampala, the site of great national celebration events such as on 9 October 1962 when Uganda celebrated independence, the Union Jack was lowered and the national anthem was sung for the very first time in public. Back to 2014: fire jugglers, acrobats, singers and schoolchildren performed at a long ceremony arranged to celebrate the country’s new Anti-Homosexuality Act, signed into law by President Museveni in February 2014.2 Pastor Martin Ssempa,3 an evangelical leader who has been one of the most vocal activists against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transsexual (LGBT) rights in the country, led a march of several hundred people who, leaving the campus of Makerere University, walked in line to join the crowd at Kololo stadium carrying signs saying ‘Mr Museveni thank you for saving the future of Uganda’, ‘Uganda Belongs to God’, ‘Obama, we want trade not homosexuality’. The event, pithily entitled the ‘National Thanksgiving Service Celebrating the Passing of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill’, was organised by the Inter-Religious Council of Uganda, an umbrella organisation of the country’s major denominations, and other groups that had supported the passage of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill (AHB) into Law, among whom there was a strong representation of Pentecostal-Charismatic churches (PCCs) and Pentecostal organisations. Speakers addressed the crowd from the impressive stage where Museveni sat beside his wife, Janet Kataaha Museveni, in large chairs surrounded by government officials, members of parliament and religious leaders. ‘Today, we come here again [to celebrate] sovereignty and freedom … [and] to take charge of our destiny,’ said David Bahati, the politician most closely associated with the promotion of the AHB starting in 2009, ‘The citizens of Uganda are with you, Mr. President. The religious and cultural leaders are with you, Mr. President. The members of parliament and the nation is behind you’ (Hodes 2014).

This event exemplifies how in recent years the rise and political action of the Pentecostal-charismatic (PC) community has impacted upon the very nature of Ugandan politics, firmly integrating morally aligned initiatives into public policy. The impact of PC discourse in the country is in particular laid bare around issues of sexuality and morality. The recent Anti-Pornography Act4 and the Anti-Homosexuality Act, both approved by Parliament in December 2013, are intrinsic to this public moralisation and religiously driven public action.

From a religious minority isolated from the public and persecuted during Idi Amin’s era (Ward 2005),5 Pentecostal-charismatic churches (PCCs) started to grow in the 90s and according to Epstein (2007) and Gusman (2009) in recent years nearly one-third of Ugandans have converted to Pentecostal-charismatic Christianity. Alongside their numerical growth their political and public participation has increased and is now very vocal. In particular regarding the issue of sexuality Pentecostal-charismatic leaders seemed to have focused their energies in articulating the immorality of homosexuality, which they often present as an external Western import that clashes with African and Christian values. The moral discourse around sexuality seemed to have united a diverse and otherwise fragmented Ugandan Pentecostal-charismatic community. As Pastor Ben articulated in an interview:

We [PCCs] are together when we discuss certain issues, certain challenges. And other issues, due to our religious freedom, divide us and we divert. With Bahati’s Bill [Anti-homosexuality Bill] you have seen all the Pentecostal churches coming together and saying the same thing. Under the same roof, coming together and making a resolution in the same day, wow!(Pastor Ben Fite, 10 February 2013, Namuwongo)

And again:

The government, they understand not philosophy or theology but numbers: the greater you are the greater the voice and the more like they are to listen. Like with the Marriage and Divorce Bill and the voting for this, we are pushing against certain aspects of this heavily. Also the issues of homosexuality and lesbianism. We find ourselves needing to unite to fight against this. When talking about the Anti-Homosexuality Bill and the Marriage and Divorce Bill we have to unite.(Rev. Timothy Kibirige, Associate Superintendent of Pentecostal Assemblies of God – Uganda and Pastoral Team Leader of Entebbe Pentecostal Church, Kampala, 25 March 2013)

This chapter is concerned not only with religious perceptions of sexuality but also with the tightening relationship between politics, the nation and public religion in Uganda. Focusing on the analysis of a Pentecostal-charismatic church in the capital Kampala, Watoto, the chapter will show how the sexuality discourse has entwined with and been promoted by PCCs who in doing so are becoming instrumental within the new nationalist discourse of public regeneration in the country. Ultimately the analysis is informed by the idea that public politics in Uganda today simply cannot be understood in isolation from religion and new forms of religious public interventions.

Pentecostalism and politics in Uganda

In the colonial and post-colonial history of Uganda organised religion has played an inextricable role in national politics. Historically both the Anglican and Catholic Church have held a near duopoly on Ugandan Christianity (according to the Ugandan Census 2002, 85.4 per cent of the population declared to belong to a Christian denomination, Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2007). Religious sectarianism has defined Ugandan politics since Christianity first took hold in the Bugandan monarchy (Rowe 1964). For Gifford, ‘the rivalry between Anglicans and Catholics has become institutionalized in their respective political parties; Obote’s Ugandan People’s Congress was linked to the Anglican Church of Uganda, and the [opposition] DP (Democratic Party) to the Catholic Church’ (Gifford 2000, 105). During the decade before independence political parties began to form based largely along Catholic and Anglican divides (Ward 2005, 112). While Milton Obote, a Protestant and the nation’s first president, ‘endeavoured to create a secular state, in which religion did not intrude into the political sphere … entrenched religious loyalties, which he himself could not transcend, make it hard for him to succeed’ (Ward 2005, 112). Religious divisiveness characterised most of the post-independence period.

Early Pentecostal churches began to take root in the late 1950s and in the 60s but in the following decade Idi Amin’s regime banned independent churches, further strengthening the hold of the Catholic and Anglican traditions. According to Ward, Amin – the only Muslim to serve as President – ‘was not against Christianity as such. But he greatly feared the Churches as centres of opposition to his rule. He prohibited altogether the small evangelical and Pentecostal churches which had proliferated in the 1960s’, intensifying the powers of the Catholic and Anglican traditions (Ward 2005, 115). PCCs’ consolidation and affirmation in the country is concomitant to the Museveni’s regime.

Gifford (1998) positions the rise of early born-again churches in parallel to Museveni’s era and for both 1986, when the National Resistance Movement (NRM) came to power, proved a historic year. Beyond the global momentum of the Pentecostal-charismatic movement, PCCs found relevance in Uganda due to two distinct factors: the reforms and ideology of the Museveni’s regime that saw in PCCs a non-sectarian ally to redevelop the country, and the HIV epidemic. Ideologically, in fact, PC churches existed outside the political-religious divides of the Anglican and Catholic Church, and proved in harmony with the goals of the NRM (Gifford 1998). According to Freston, relatively early on Museveni and the NRM saw themselves ‘as creating a “new dispensation”. The Catholic and Anglican churches are of the old dispensation, whereas the “born again” movement is part of the reconstruction’ (Freston 2004, 142). Furthermore their theology and practical ethos founded on prosperity, accumulation and regeneration really worked in affinity with the NRM’s national reconstruction project. For Gifford, ‘their enormous growth, public profile and impact were evident to all’ and while the theological vantage of churches greatly differed, they were unified in a stress of economic and material success and accumulation (Gifford 2000, 111).

Early PC churches of the late 1980s and 90s kept politics at arm’s length. In line with Corten and Marshall-Fratani’s (2000) analysis of PC Christianity in Africa, new Pentecostal churches maintained a relatively apolitical stance espousing ‘an ideological commitment to a clear separation between the life of the ‘saved’ and the ‘ways of the world’ (Jones 2005, 497). Throughout the 1990s, the initially marginal churches experienced prolific growth and their emergence into the public started to take place when the PC community gained significant influence in the Ugandan public sphere because of HIV. The HIV epidemic is inextricable from the proliferation, institutionalisation and increased politicisation of the PC community. Beginning around 2000, HIV provided the conditions for PCCs to transition into or form Faith-based Organisations (FBOs).

International flows of development aid and local conditions came together and fused political initiatives with the religious agenda of the PC community. Two contributing factors helped institutionalise the PC community around HIV: the theological stance and international funding. First, ‘the epidemic itself encouraged a significant theological refocus among Pentecostal churches … from an “otherworldly” to a “this-worldly” attitude, from the urgency of saving as many souls as possible in the short term, to long-term programs, with a stress on the future of the country’ (Gusman 2009, 68). Second, beginning in 2004 PEPFAR6 funds originating from the United States Government, redirected national strategies around HIV to ‘morally’ informed campaigns. In four years PEPFAR allocated around $650 million to Uganda (ibid). PCCs capitalised on PEPFAR funds that were ‘channeled into FBOs working on HIV/AIDS prevention issues, particularly those concerning abstinence and faithfulness’ (ibid). According to Cooper (2014) and Patterson (2011) US evangelical and African Pentecostal-charismatic churches have been among the primary beneficiaries of PEPFAR funds. In turn, in recent years US evangelical efforts in sub-Saharan Africa have experienced a profound increase (McCleary 2009; Hearn 2002). For Cooper, PEPFAR ‘can be said to have institutionalized [the foreign and domestic evangelical] presence in US humanitarian aid by enshrining the moral prohibitions of conservative Christianity in the very conditions of its funding’ (Cooper 2014, 3).

PEPFAR was not the only development initiative that has helped to institutionalise the Pentecostal presence. Under George W. Bush’s administration an executive order established an official office for Faith-Based and Community Initiatives in the US Agency for International Development (USAID) ‘with the express purpose of facilitating foreign aid contracts with faith-based service providers’ (Cooper 2014, 3). USAID issued a subsequent ruling that prohibited discriminatory practices against religious organisations. For Clarke, this equalised ‘the treatment of secular and religious organizations [but] effectively tilts the balance in favour of the latter’ (Clarke 2007, 82). Yet the increased prominence of faith-based actors is not solely the result of US interventionism. According to Cooper, ‘the theological turn in international emergency relief both responds to and serves to amplify on-going developments in the domestic politics of sub-Saharan African states, where non-governmental organizations in general, and religious organizations in particular, have come to play an increasingly prominent role in the provision of social services’ (Cooper 2014, 4). In Uganda PCCs became increasingly involved in HIV initiatives and in this way national strategies took on a moral character for prevention no longer based on ‘secular’ approaches but on religiously and morally driven public interventions.

HIV was significant not only for PCCs but also because it changed the nature of the public sphere by creating for the first time open dialogue around sexuality. For Tamale ‘the HIV/AIDS Pandemic has in many ways flung open the doors on sexuality’ (Tamale 2003, 5). In a break from the past, HIV made sex and consequently sexuality an acceptable topic for public discussion. For Epprecht, ‘in recent years [the linguistic] subtlety [when discussing homosexuality] has begun to change quite dramatically … [and] depictions of same-sex sexuality are now becoming increasingly explicit and frank’ (Epprecht 2008, 8). HIV redefined discussions of sexuality in the Ugandan public sphere. Institutionalised discrimination against homosexuality was introduced with the ‘former British colonial power through legislation aiming at re-educating “the native subjects” in sexual mores’ (Strand 2012, 566), yet sexuality has remained a taboo topic in public circles. With the entrance of sexuality into the public, PC public action started to be diverted into promoting their own conservative interpretations of morally acce...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction: public religion, homophobia and the politics of homosexuality in Africa

- PART I The politicisation of homosexuality

- 1 ‘For god and for my country’: pentecostal-Charismatic churches and the framing of a new political discourse in Uganda

- 2 Uniting a divided nation? Nigerian Muslim and Christian responses to the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act

- 3 Discourses on homosexuality in Egypt: when religion and the state cooperate

- 4 ‘We will chop their heads off’: homosexuality versus religio-political grandstanding in Zimbabwe

- 5 ‘Un-natural’, ‘un-African’ and ‘un-Islamic’: the three pronged onslaught undermining homosexual freedom in Kenya

- 6 Côte d'Ivoire and the new homophobia: the autochthonous ethic and the spirit of neoliberalism

- PART II Global and local mobilisations

- 7 An African or un-African sexual identity? Religion, globalisation and sexual politics in sub-Saharan Africa

- 8 The extraversion of homophobia: global politics and sexuality in Uganda

- 9 Religious inspiration: indigenous mobilisation against LGBTI rights in post-conflict Liberia

- 10 Islamic movements against homosexuality in Senegal: the fight against AIDS as catalyst

- 11 One love, or chanting down same-sex relations? Queering Zimbabwean Rastafari perspectives on homosexuality

- 12 Narratives of ‘saints’ and ‘sinners’ in Uganda Contemporary (re)presentations of the 1886 story of Mwanga and Ganda ‘martyrs’

- PART III Contestation, subversion and resistance

- 13 Critique and alternative imaginations Homosexuality and religion in contemporary Zimbabwean literature

- 14 Christianity, human rights and LGBTI advocacy: the case of Dette Resources Foundation in Zambia

- 15 ‘I was on fire’: the challenge of counter-intimacies within Zimbabwean Christianity

- 16 Critical realism and LGBTIQ rights in Africa

- Appendix African LGBTI manifesto

- Index