- 174 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Recent years have seen an explosive growth in the phenomenon of people visiting locations from popular novels, films or television series. Places of the Imagination presents a timely and insightful analysis of this form of media tourism, exploring the question of how best to explain the increasing popularity of media tourism within contemporary culture. Drawing on extensive empirical and interview material, this book examines the representation of landscapes in popular narratives that have inspired media tourism, whilst also investigating the effects over time of such tourism on local landscapes, and the processes by which tourists appropriate the landscape, experiencing and accommodating them into their imagination. Oriented around three central case studies of popular television detective shows, famous films and classic literature, Places of the Imagination develops a new theoretical understanding of media tourism. As such, it will appeal to sociologists and cultural geographers, as well as those working in the fields of media and cultural studies, popular and fan culture, tourism and the sociology of leisure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Places of the Imagination by Stijn Reijnders in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Hospitality, Travel & Tourism Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

On a pleasant summer’s day, a visitor to Exeter College, one of the oldest colleges in Oxford, has a good chance of coming across a group of tourists. Of course, there is nothing unusual in this: most colleges attract a constant stream of tourists. But these visitors are not looking at the lovely, neo-Gothic chapel or the view of Radcliffe Square. Instead, they are pointing their cameras at a corner of the lawn, an apparently insignificant bit of grass. It is also striking that the normal chatter of tourists has given way to a solemn silence, where the only sound to be heard is the clicking of camera shutters. What’s happening here? This is the exact place where Inspector Morse – the main character in the television series of the same name – was struck down by a heart attack. In the last episode of the detective series, which was popular around the world, Inspector Morse collapsed, at just this spot on the lawn of Exeter College, to pass away several hours later in a local hospital.

Figure 1.1 Tourists take photographs of the lawn at Exeter College during the Inspector Morse Tour

Source: Photograph by Elvire Jansen.

In Search of Morse

For more than ten years, the Inspector Morse Tour has been one of the most popular tours in Oxford. Despite the fact that the series ended in 2000, every year a steady stream of around 3,500 tourists still pay to follow in the footsteps of the rather sombre, melancholic Inspector Morse and his assistant, Lewis.1 Taking approximately two hours, the tour takes the tourists past the most important film locations in the centre of Oxford, from fictional crime scenes to Morse and Lewis’ favourite pubs. The link to Morse is visibly honoured in some of these locations. Thus, the Randolph Hotel has a special ‘Morse Bar’, whose walls are covered with photographs of the actors in the company of Colin Dexter, the author of the Morse series.

The Inspector Morse Tour is no isolated incident. In other cities similar tours are organized at the locations of popular films, television series or novels. For example, New York has its Sex and the City Tour, in which buses full of Sex and the City fans motor through the city, past the apartments, cafes and clothes shops that are featured in the series. In the same way, fans of Dracula get their kicks in the Romanian province of Transylvania.

One of the most large-scale examples of recent years is perhaps The Lord of the Rings, which has inspired thousands upon thousands of ‘jet-setters’ to set off for New Zealand. Although precise figures are unavailable, there are estimates of noticeable increases in the number of tourists from overseas in the first few years after the release of this globally popular film trilogy. These fans received a warm welcome in New Zealand and continue to do so. In some cases almost literally: anyone arriving at Wellington airport at that time was made officially welcome to ‘Middle Earth’. Numerous local businesses and travel agencies capitalized on this new trend and it is rumoured that the New Zealanders themselves were actually proud of the increase in interest in their country (Beeton 2005; Roesch 2009).

Nevertheless, this form of tourism is not always welcomed everywhere with open arms. A notorious example of this is the novel The Da Vinci Code and the eponymous film, which, at the beginning of the last decade, prompted a genuine boom in the number of visitors to locations in Paris, London and Rosslyn. The Louvre Museum in Paris attracted a record number of visitors in 2005. It turned out that this interest was not generated by a particular exhibition but by the fact that this temple of the fine arts had figured in the popular thriller The Da Vinci Code. Thousands of people made their way to the Louvre in order to see with their own eyes the spot where the fictional murder in the thriller had taken place (Braun 2006). A similar fate befell the little Rosslyn Chapel, which became one of the most popular tourist destinations in Scotland as a result of The Da Vinci Code, complete with crush barriers, entrance gates and a gift shop next door. The director of the Rosslyn Chapel resigned during the course of 2006. He could no longer bear the sight of this, for him, holy place being turned into ‘The Da Vinci Code Disneyland’ (Johnston 2006).

Figure 1.2 Travellers to Wellington Airport were welcomed to ‘Middle-earth’

Note: The première of The Lord of the Rings stimulated an enormous amount of tourism to New Zealand. Thousands upon thousands of fans went off in search of the locations of this world famous film trilogy.

Source: Photograph by Stijn Reijnders.

Media tourism

Strictly speaking, the fact that tourists are drawn to the scene of a fictional story is not a new phenomenon. An early example of this would be the British detective Sherlock Holmes, whose supposed home 221b Baker Street already attracted visitors at the beginning of the twentieth century (Wheeler 2003). In a more general sense, these tourists are part of a longer tradition of literary tourism. In her book The Literary Tourist (2006), the British literary scholar Nicola Watson describes how a fascination developed in the nineteenth century for the graves of famous authors, the houses where they were born, as well as the settings they described in their works, such as Sir Walter Scott’s Loch Katrine or the Brontë sisters’ Haworth (cf. Seaton 1998; Hardyment 2000). In the oral folk tradition, there is an even longer tradition of ‘legend trips’, where people traveled to locations – castles, bridges or cemeteries – associated with popular ghost stories (Ellis 1989, 2001).

Figure 1.3 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle set the house of fictitious detective Sherlock Holmes at 221b Baker Street

Note: In 1990 the Sherlock Holmes Museum was set up at this location. The layout of the museum is based on descriptions from the books.

Source: Photograph by Stijn Reijnders.

Nevertheless, there would seem to be an increase in scale and a popularization of such trips in the current age. In the nineteenth century, literary tourism was limited, with some notable exceptions, to a relative small group of lovers of literature (Watson 2006: 131–200), whereas each of the contemporary TV tours attracts thousands of tourists every year. Visiting ‘fictional’ locations from ‘low culture’ has grown into an important economic activity, with far-reaching consequences for the communities involved, the local inhabitants, and the tourists themselves (Beeton 2005). These tours provide the framework within which many people get to know a new city such as Oxford, New York or Ystad. This can no longer be considered a rare activity, but rather a widespread phenomenon: a growing niche in the global tourist market, variously labelled ‘TV tourism’, ‘movie tourism’, ‘movie-induced tourism’ or ‘film-induced tourism’ (Beeton 2005).2 In this book I have chosen to introduce a more inclusive term: ‘media tourism’. Not only does this term do justice to the rich history of literary tourism, it also recognizes the multimedia character of many contemporary examples such as Inspector Morse, Lord of the Rings and The Da Vinci Code.

Little is known about the popularity of these TV detective tours. Influenced by post-modern philosophies about hyper-reality (Baudrillard 1981) and deterritorialization (Deleuze and Guattari 1988), communication scholars have, for a long time, predominantly emphasized the virtual character of our media culture. Following the work of Baudrillard, the general argument goes that post-modern individuals can no longer distinguish between what is real and what is not because of the excess of media images to which they are exposed. Even more, the virtual media world has become their most important frame of reference. According to this argument, people would no longer need to travel, since they could experience ‘virtual tourism’ just by watching television (Gibson 2006). Based on these prevailing theoretical models, it is difficult to explain why people make the effort to travel to a place with which they are already familiar from the media (Rojek 1993a: 69–72).

Recently, partly in response to these post-modern philosophies, interest in the material, more physical aspects of our media culture has grown – a development that within media studies has been called the ‘spatial turn’ (Falkheimer and Jansson 2006). Because of this, the phenomenon of media tourism has also come more under the spotlight.

For example, studies have described the attraction of the set of Coronation Street at Granada Studios near Manchester (Couldry 2000) and the Manhattan TV Tour in New York (Torchin 2002). Other scholars have focused on the popularity of Blade Runner in Los Angeles (Brooker 2005), Braveheart in Scotland (Edensor 2005), The Sound of Music in Salzburg (Roesch 2009), the X-Files, Smallville and Battlestar Galactica in Vancouver (Brooker 2007), Harry Potter settings in the UK (Iwashita 2006), and sites where The Lord of the Rings was shot in New Zealand (Tzanelli 2004, 2007; Beeton 2005; Roesch 2009). In addition, studies have described the effects of these tours on the local community. For example, Mordue (2001) interviewed residents of Goathland, after the village became a tourist hotspot as a result of the British TV series Heartbeat. Similarly, Beeton (2005: 123–9) looked at the effects of tourism in Barwond Heads, the Australian village that served as the backdrop for the popular movie, Sea Change.

This signifies the emergence of a recognized, interdisciplinary field of research, consisting of aspects of, among other things, media studies, communication science, tourism studies, cultural geography and fan studies. In spite of the increasing interest in the phenomenon of media tourism, many questions remain as yet unanswered. Little is known about the dimension of media tourism relating to content: why do some media products lead to media tourism while others don’t? What characteristics of a story contribute to its attraction? Do different genres possibly lead to various sub-forms of media tourism? These questions have in part, already been posed in existing studies (cf. Roesch 2009), but no satisfactory answer has as yet been forthcoming.

Figure 1.4 Participants in the Sex and the City Tour enjoying a Cosmopolitan in the bar from the television series

Source: Photograph by Maria Heemskerk.

An underlying, more philosophical question concerns the relationship between the story and its represented landscape. Are the origins of media tourism entirely contained in the story, which ascribes meaning to the represented landscape? Or should the answer be sought in the landscape itself, which as a physical-material actuality plays an active role in the creation of certain stories? Many stories do indeed seem to be anchored in a particular landscape. By way of illustration: Dracula finds a logical home in the mysterious mist-encircled mountainous landscape of Transylvania. It is difficult to imagine that Stoker would have chosen to set his story of the bloodthirsty count in, for example, a Dutch Polder. Has the popularity of the Dracula tours, then, entirely arisen out of the story, does it lie in the landscape or is it a combination of the two? And if it is a combination, how does such an assemblage come about?

Besides this, what are the consequences of media tourism for the local communities? Media tourism often follows a capricious pattern: it emerges suddenly but can just as quickly vanish again when the public becomes gripped by some new blockbuster. What consequences do these unpredictable tourist streams have for those who – not necessarily through their own design – have to deal with them? The commercial, socio-political and ecological consequences vary widely in each case, but it may also be possible to discern more widespread patterns.

Finally, one of the most important questions, about which we are still groping in the dark, is the meaning that media tourism has for the tourists themselves. It is remarkable that we know so little about this, for it is precisely the personal experiences of the fan/tourist and the meaning that they ascribe to the event that form the crux of the entire phenomenon. There, in the head and heart of the fan/ tourist, resides the fascination and motivation to visit these locations. That is where the initial moment of connection takes place, the moment in which the world of the imagination temporarily comes together with – or perhaps perfectly contrasts with – the sensory experience of physical reality. The essence thus lies in penetrating more deeply the world of the imagination. A quest of this sort, however, demands a theoretical perspective, which, like a compass, can give direction to our research.

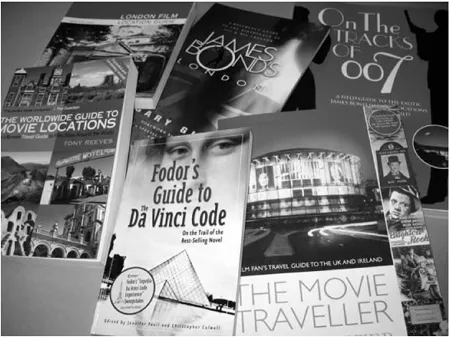

Figure 1.5 Various travel guides specialized in media tourism

Note: These travel guides provide information about the locations where well-known films and television series were shot.

Source: Photograph by Stijn Reijnders.

Places of the Imagination

With that aim in mind, the following chapter will introduce a new approach. The point of departure is the research of French historian Pierre Nora into the working of collective memory. In the 1980s, Nora showed how lieux de mémoire such as national monuments and battlefields act as a validation of collective memory. In the same way, as will be more comprehensively illustrated in the following chapter, we can also speak of lieux d’imagination (places of the imagination) which are not so much concerned with collective memory, as collective imagination. Lieux d’imagination are physical locations, which serve as a symbolic anchor for the collective imagination of a society. By visiting these locations, tourists are able to construct and ‘validate’ a symbolic distinction between imagination and reality.

In the following chapters, the concept of lieux d’imagination (places of the imagination) shall be applied to, and at the same refined by, three actual examples of media tourism. The first part of this research shall involve an international comparison of three popular TV detectives, who each have inspired significant tourist streams: Inspector Morse in Oxford, Baantjer in Amsterdam and Wallander in the Swedish coastal town of Ystad. The comparison starts with a textual analysis of the content of these series: I shall investigate what role or meaning representations of local landscapes (or cityscapes) have within the narrative structure and development of Inspector Morse, Baantjer and Wallander. I shall also pay attention to the relationship between the subject matter of the content and its exploitation for tourism purposes. For example,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

- PART I TV DETECTIVES

- PART II JAMES BOND

- PART III DRACULA

- Appendix

- Filmography

- References

- Index