- 229 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Economic historians have perennially addressed the intriguing question of comparative development, asking why some countries develop much faster and further than others. Focusing primarily on Europe between 1914 and 1939, this present volume explores the development of thirteen countries that could be said to be categorised as economically backward during this period: Albania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey and Yugoslavia. These countries are linked, not only in being geographically on Europe's periphery, but all shared high agrarian components and income levels much lower than those enjoyed in western European countries. The study shows that by 1918 many of these countries had structural characteristics which either relegated them to a low level of development or reflected their economic backwardness, characteristics that were not helped by the hostile economic climate of the interwar period. It explores, region by region, how their progress was checked by war and depression, and how the effects of political and social factors could also be a major impediment to sustained progress and modernisation. For example, in many cases political corruption and instability, deficient administrations, ethnic and religious diversity, agrarian structures and backwardness, population pressures, as well as international friction, were retarding factors. In all this study offers a fascinating insight into many areas of Europe that are often ignored by economists and historians. It demonstrates that these countries were by no means a lost cause, and that their post-war performances show the latent economic potential that most harboured. By providing an insight into the development of Europe's 'periphery' a much more rounded and complete picture of the continent as a whole is achieved.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Europe's Third World by Derek H. Aldcroft in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Characteristics of the European Periphery

The definition of the periphery used in this volume is an economic rather than a geographic one. European peripheral countries are the poor ones, those that largely missed out on the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century which transformed the economies of Western Europe and the United States. As a working concept we have defined the impoverished peripherals as those countries which in the early twentieth century still had around one half or more of their population dependent on agriculture and with incomes per capita of less than 50 per cent of those of the advanced nations of Western Europe. On this basis, therefore, we would then encompass much of Eastern Europe (Poland, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria), Spain, Portugal, Greece and Turkey in Southern Europe, along with the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and ending up with little Albania. It so happens that most of these countries could also be classed as peripheral in a geographic sense and many of them were fairly small in terms of population.

The only debatable issue was whether or not to include Italy since, according to two Spanish scholars (Molinas and Prados de la Escosura 1989, 397), Italy and Spain had very similar incomes per head in 1910 and 1930. After careful consideration it was decided to exclude the former country. Other sources suggest that Italy had a higher per capita income than Spain; but, that apart, the depth of structural change in Italy was deeper than in the case of Spain, and more akin to the Western European pattern. Structural change and income per capita growth tended to go hand-in-hand in Italy, whereas in Spain structural adjustment lagged behind improvements in income per capita (see Molinas and Prados de la Escosura 1989, 397). More generally, one gets the impression from a reading of the evidence that Italy was a more mature country than Spain, with a stronger integration into the international economy and a more pronounced role in international affairs. Known as the least of the Great Powers and lacking significant natural resources, Italy was a successful belligerent in the First World War and subsequently, under Mussolini, became an aggressive military state. In fact, a country that by the late 1920s had the world’s second largest air force, the third largest army and the fifth largest navy, and was soon to embark on imperialistic ventures, could scarcely be classed as a poor European peripheral country (Morewood 2005, 26).

A word about regional definitions is appropriate at this stage since these can be a source of confusion. This is especially the case with Eastern Europe or East-Central Europe, which can be a definitional nightmare. Broader definitions of East-Central Europe can include some twelve to fourteen countries. Kofman (1997, 3), for example, defines East-Central Europe to mean Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Romania, Yugoslavia, Albania, Bulgaria and Greece, which includes 10 of the countries covered in this volume. However, Greece can be listed under Southern Europe, while Bulgaria, Romania, Yugoslavia, Greece and Albania are also classed as Balkan countries. For simplicity we have adopted the following categories. The region frequently referred to as Eastern Europe includes six countries – Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. The last of these is not included in this volume since its level of development was more akin to that of the West than to that of the peripheral countries. The term Balkans is used throughout to refer to the three main Balkan countries of Bulgaria, Romania and Yugoslavia. Spain, Portugal and Greece are part of Southern Europe, which can also include Turkey by virtue of its small presence in Europe. The term Iberian Peninsula refers to Spain and Portugal. Turkey and Albania are normally mentioned separately, while Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania come under the heading of the Baltic states.

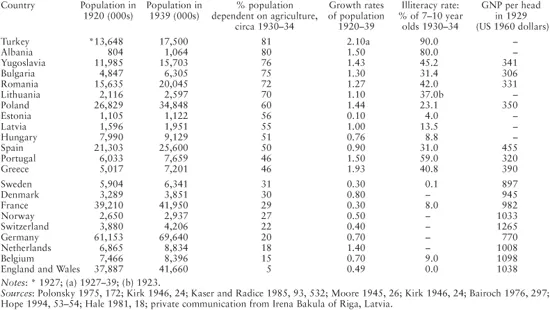

Most of the 13 countries covered in this volume had several features in common. A large proportion of the population was dependent on the primary sector, principally agriculture, for their livelihood. This ranged from 45–50 per cent in the case of Southern Europe (Spain, Portugal and Greece), between 50 and 60 per cent in the case of Hungary, Poland and the Baltic provinces, excepting Lithuania, to 70–81 per cent in the Balkans (Bulgaria, Romania and Yugoslavia), Albania and Turkey (see Table 1.1). Almost everywhere agricultural systems and methods of production were backward and fairly unyielding; by Western standards productivity levels were very low, while medieval-type strip farming was still quite common in some regions, especially in the Balkan countries. Most operations in peasant agriculture were performed by human labour or by animal-drawn implements. Peasant life was not a pleasant one and general living conditions were often very primitive (Bideleux and Jeffries 1998, 449–52). Land ownership patterns varied a great deal and there were many changes in the course of the period (see later chapters), but few countries, apart perhaps from the Baltic states, emerged with patterns of land ownership and cultivation that made possible more efficient farming practices, though productivity levels still fell well short of those in Western countries.

Table 1.1 Population and Income Levels for Selected Countries

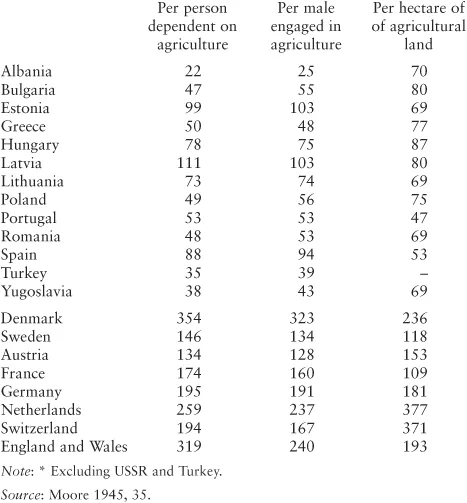

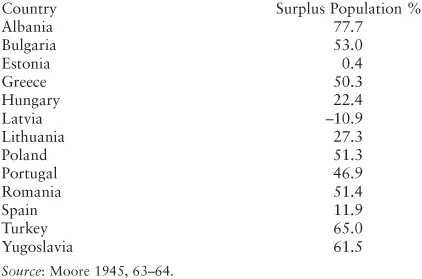

The backwardness of agriculture can be measured by the low levels of productivity as against Western standards. In terms of both land area and persons engaged in agriculture productivity levels were but a fraction of those in Western Europe (see Table 1.2). It follows therefore that there was enormous potential surplus population in agriculture, except in Estonia and Latvia, had agricultural practices conformed more closely to best practice techniques of Western Europe (see Table 1.3). In some cases marginal productivities on the land were probably zero or negative, which implies that drawing people out of agriculture would have raised the average productivity level. The only problem here was that unless commensurate changes were taking place in the rest of the economy there was nowhere for redundant agricultural labour to find employment.

Table 1.2 Indices of Agricultural Productivity in Calorie Units (average 1931–35, Europe* = 100)

Table 1.3 ‘Surplus’ Agricultural Population Assuming Existing Production and European Average Per Capita Level (circa 1930)

Low levels of efficiency in farming inevitably led to pressure on land resources, a situation intensified by the rapid population growth during the interwar period, which came at the most inopportune time as far as the peripheral countries were concerned. Apart from the exceptional case of Estonia, most countries had population growth rates well in excess of those in Western Europe. In Albania, Turkey, Portugal, Greece, Poland and the Balkans, population was growing at well over 1 per cent per annum in the interwar period, compared with only 0.5 per cent for England and Wales, 0.7 per cent in Belgium and Germany, and as low as 0.3 per cent in France and Sweden (see Table 1.1). Much of this rapid expansion can be attributed to the very high birth rates at a time when death rates were falling rapidly, due to health and medical improvements. But in some countries, as for instance Romania and Greece, populations were augmented considerably by large additions resulting from territorial gains and population migrations following the postwar peace settlements. Greece had an influx of well over a million expatriate Greeks (adding possibly one quarter to her population total), the main contingent coming from Turkey following the Greek defeat in Asia Minor in 1922, as well as smaller numbers from Balkan countries. In return Turkey received some 400,000 of its own nationals from Greece.

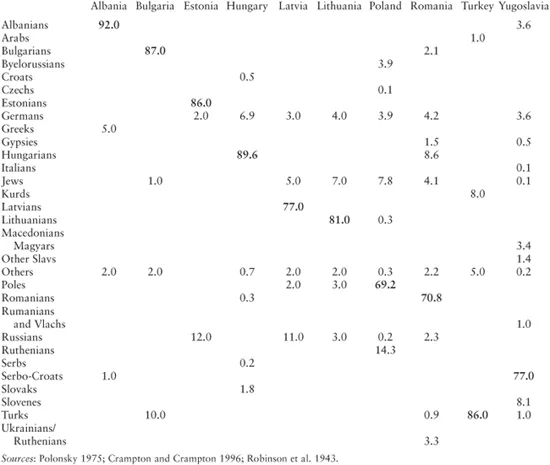

Despite the exchange of populations following the war and the reduction in minority status by the peace treaty settlements, many of the Baltic and East European countries still had large minority populations. Table 1.4 gives a breakdown of the ethnic composition of the countries in question, with the predominant group given in bold type. Apart from Albania, 10 per cent or more of the populations of these countries consisted of ethnic minorities, while in the case of Poland and Romania the proportion was as high as 30 per cent. The new Hungarian state on the other hand, while more homogenous in ethnic terms, had some three million of its nationals living as minorities outwith its borders. In some countries there were up to a dozen or more different minority groups. The worst case was that of Yugoslavia. Though Slavic interests accounted for more than three quarters of the population, this figure masks the actual diversity and the potential for conflict. The two main groups, the Serbs and the Croats, were scarcely the most congenial of partners, nor for that matter were the Slovenes. Moreover, the main Serbo-Croat contingent included a not inconsiderable number of Bosnian Muslims, Macedonians, Bulgarians and Montenegrins. Altogether there were over a dozen assorted minority interests, including Germans, Magyars, Romanians, Albanians, Turks, Poles, Italians, Gypsies, Bulgarians, Czechs/Slovaks and Macedonians, none of whom could assimilate easily one with another. Moreover, most of them suffered minority discrimination and persecution at one time or another at the hands of the dominant Serbs. In fact the ethnic problems of the new Yugoslav state were exacerbated by the fact that the Serbs, who represented about 40 per cent of the population, tended to monopolise the positions of power within government and administration and paid lip-service to the interests of their minority nationals. As Berend comments, ‘No other country in Europe – except the Soviet Union, which had preserved the old multinational empire – possessed such a diverse population’ (Berend 1998, 171).

Perhaps even more fascinating were the tiny pockets of ethnic groups left over from a bygone age. In Poland there were small numbers of Tartars, while nomads and semi-nomads, for example the Vlachs, were to be found in the Balkan countries (Crampton and Crampton 1996, 2). More significant from the point of view of political developments were the pockets of Germans and Jews in many countries. Linguistic divisions, though a guide to ethnicity, are even more complex because of much inter-linguistic mixing in some regions. Religious affiliations were equally complex. Though the most important were Protestant, Roman Catholic, Orthodox, Greek Catholic and Muslim, there were also many smaller religious sects.

This ‘ethnological soufflé’, as Tiltman (1934, 266) called it, was bound to give rise to serious problems, some of which have persisted to the present day. Minority nationality problems were in fact ‘one of the most acute causes of tension in east Europe throughout the interwar period’ (Hauner 1985, 68). It is true that the countries with significant minority interests were enjoined, under the League of Nations minority treaties which they signed, to observe good behaviour towards their alien residents and to avoid the exercise of discrimination. In practice there was a notable reluctance to abide by their obligations. Generally speaking, ‘the states were mainly concerned with interpreting the provisions in the most restrictive possible sense and used every device to vitiate their effect’ (Robinson et al. 1943, 264). In few cases, therefore, were minority groups accorded equality of treatment in government and administration, and in the dispensation of economic and social services.

As well as being predominantly agrarian-based, the populations of these countries were very illiterate judged by Western standards. About half the countries had illiteracy levels of 40 per cent or more in the early 1930s; in Portugal the rate was nearly 60 per cent and in the case of Albania and Turkey it was as high as 80–90 per cent. Only the Baltic states – excepting again Lithuania – Hungary, and to a lesser extent Poland had relatively high levels of literacy (see Table 1.1). Everywhere illiteracy was considerably higher among females than among males.

High agrarian dependence inevitably meant that modern industry played a relatively small role in the economies of the peripheral countries. At the extreme, Turkey and Albania probably had less than 10 per cent of their labour forces employed in this sector, and even then much of it consisted of small-scale domestic or workshop manufacture. The Balkan countries fared little better in this regard, whereas Poland and Hungary had developed more substantial industrial interests before 1914. The Baltic states also had a thriving industrial sector before 1914 which mainly served the Russian market, though much of it was subsequently lost as a result of war and revolution. Yet however small and insignificant the industrial sector, most countries had experienced some modern development before 1914, even if only through the backwash effects of Western development and the influx of Western capital and technology. True industrial development was often highly concentrated spatially, sometimes forming islands of capitalism in a sea of primitivism, while the level of efficiency fell well short of Western standards (see Berend and Ranki 1982).

One feature of the limited industrial development was the marked presence of foreign capital in modern joint stock enterprise. This was true both before and after the war despite attempts by nationalist politicians to extend the practice of nostrification principally through increased state holdings. Some 50 per cent of the total Latvian stock capital was in foreign hands in 1925, while by the early 1930s the proportions of joint stock capital owned abroad in Poland was two fifths, one half in Hungary and three fifths in Bulgaria (Hinkkanen-Lievonen 1983, 335). Most other countries had a relatively high proportion of foreign capital in modern enterprise, both in industrial undertakings as well as in raw material and mineral extraction, a reflection of the low level of domestic accumulation. In some sectors foreign ownership was dominant, as in the case of the Romanian oil industry.

Table 1.4 Ethnic Composition of Peripheral Countries circa 1930 (%)

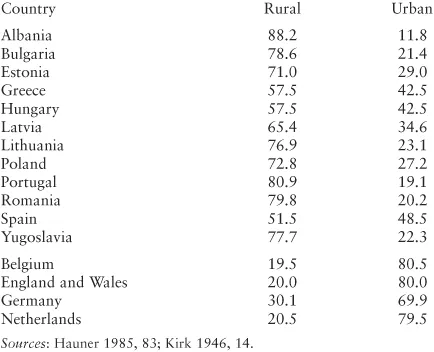

Retarded industrial development also meant a low level of urbanisation. The rural–urban split of population was in many cases almost the reverse of that in West European countries. One or two countries, notably Hungary, Greece and Spain, had relatively high levels of urbanisation, but even in these cases it was still only about half the Western level. Otherwise, the urban proportion was a third or one quarter of that in the West, and even less in the case of Albania and Turkey (see Table 1.5).

Table 1.5 Rural/Urban Distribution of Population (circa early 1930s)

The trade orientation of European peripheral countries was consistent with their low level of development. Export–product ratios were fairly low by Western standards, especially for Spain, Portugal, Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, Turkey and Albania, which indicates a relative lack of integration in the international economy. On the other hand, low export–product ratios would lessen the strength of the dependency theory (see Hanson 1986, 83, 93 and Chapter 2 of the present volume). However, Hungary and Romania, along with the Baltic states, had somewhat higher ratios before 1914, though in the case of the Baltic states this was very much a consequence of their serving the Russian market.

The composition of trade reflected the domestic economic structure of these countries. Primary commodities tended to dominate the export trade, sometimes with heavy dependence on one or two products. In the case of Greece, tobacco accounted for some 55 per cent of all exports in 1926–30, while three commodities (tobacco, dried fruit and wine) made up about 80 per cent of total exports (Freris 1986, 87). Romania’s dependence was almost as great, since cereals and forest and petroleum products accounted for over 77 per cent of all exports. In Bulgaria cereals, tobacco, and eggs and livestock accounted for 73 per cent, while for Yugoslavia cereals, livestock and forest products made up 59 per cent (Lampe and Jackson 1982, 368–69). Finished goods, on the other hand, formed a very small component of exports, especially in the Balkans and in Albania and Turkey, though in the case of Poland and Hungary they were more substantial at about 20–25 per cent (Polonsky 1975, 178). Conversely, imports consisted mainly of manufactured and semi-manufactured goods, though some countries also had a not insignificant food import component. The fact that some of the countries were dependent on food imports despite their large agrarian interests is eloquent testimony to the failure of their agrarian systems to respond to the needs of rapidly growing populations.

Another feature of the peripheral countries was their poor infrastructure facilities, which was partly a consequence of their low level of urbanisation and their relative poverty. Based on five separate measures, that is, transport, communications, housing supply, health care, and educational and cultural services, the European peripherals generally scored badly, with Spain, Bulgaria, Romania, Portugal, Turkey and Albania bringing up the rear (see Table 1.6). While low incomes and a limited tax base inevitably reduced the scope for state expenditure on these facilities, it should also be noted that a relatively high proportion of government budgets was devoted to military activities, administrative costs and debt service. Thus by Western standards the provision of housing, sanitation, health care, welfare services and educational facilities was very poor in the peripheral countries of Europe.

Table 1.6 Infrastructure Levels Based on Five Components*

One notable fe...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables

- General Editor’s Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introductory Note

- 1 Characteristics of the European Periphery

- 2 Peripheral Europe Before 1914

- 3 Peripheral Europe in the Interwar Setting

- 4 The Balkan States

- 5 The Baltic States

- 6 Poland and Hungary

- 7 Spain and Portugal

- 8 Greece, Turkey and Albania

- 9 Development Stalled?

- References

- Index