![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Medical Pluralism, Healing, and Dreams in Greek Culture

Steven M. Oberhelman

The history of medicine, in both diachronic and synchronic terms, has traditionally been marked by binary oppositions. The most common opposition was “rational” medicine versus “irrational” medicine. “Rational” was associated with the scientific and the logical, with Western allopathy, while “irrational” denoted empirical and non-scientific medical practices marked by magic and primitivism. In recent years, however, scholars have argued that a medical system is culturally constructed, that is, it reflects the values and structures of the society in which it exists. Etiology of disease, treatment of disease, methods of self- and communal assessment of ill health, preventative care, types and effectiveness of medical practitioners—all are but a few facets of healing that vary across cultures and even coexist, differentially or to similar degrees, within the same culture. Medical anthropologists, employing an ethnographic approach to the social history of medicine, have shown that in a society, there exists not a single medical system, but multiple systems. Individuals resort to one or another of these systems for a variety of reasons, such as economic means, accessibility of medical practitioners, the form of illness, the healer’s past success or his reputation for dealing with specific ailments, and previous experiences of the patient and her family and friends.

Scholars have now proposed a number of intriguing methodological models for studying medical pluralism in a society. Matthew Ramsey, in his analysis of eighteenth- and nineteen-century French medicine, sees a variety of healers operating beyond elite medical professionals.1 Ramsey distinguishes between professional medicine and popular medicine, and argues that popular medicine is manifested by folk and empirical medicine and even magical practices. He does not see practitioners of popular medicine working in isolation from the medical profession, but healers of all sorts overlapping and interacting in their medical knowledge and practices. Healers are cast in social as well as economic terms: the folk healer, forming a popular culture, is part of a traditional economy; the professional physician belongs to the city and reflects “corporatism”; and the empiric healer operates on the fringes of other healing practices and participates in a market economy.2

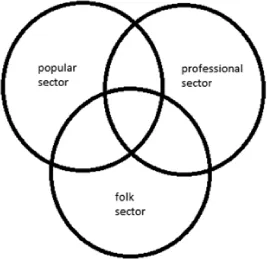

Arthur Kleinman has created a sector model for understanding how multiple healing systems coexist in a society through three overlapping sectors of health care.3 Each sector uniquely explains disease and treats health-related problems; determines the healer(s) and the patient and the ways in which they interact; and fixes on the course of treatment. The sectors are not isolated loci of healing, for people may move freely from one sector to the next and even to a third and then back again, especially when a cure is not effective or when a combination of approaches may seem optimal. The key here is the overlap and intersections of the three sectors, for a health care system in its totality is the interworkings and relationships of the sectors. As Kleinman states, health care may be “described as a local cultural system composed of three overlapping parts: the popular, the professional and folk sectors.”4 These sectors and their activities may be cast in the following Venn diagram:

Figure 1.1 Venn Diagram of Kleinman’s Medical Pluralism

The professional sector consists of organized, legally sanctioned healing professions. As Kleinman points out: “so dominant has the modern medical profession become in the health care systems of most societies (developing and developed) that studies of health care often equate modern medicine with the entire system of health care.”5 This sector includes physicians of every ilk, but also those who support them (nurses, technicians, etc.) or who complement their activities (e.g., paramedical professionals like midwives). The term “professional” is not limited to training in Western scientific medicine or the possession of credentials (say, a university diploma); it describes anyone acknowledged, or perceived, in a culture as belonging to a professional group. Of course, in many cultures, professional healers are those people recognized by law and enjoying the power of the medical establishment behind them, but in other cultures no formal licensure exists. We may think of classical Greece as an example; no doctor had a diploma or was accredited, and his reputation ultimately rested on his successes and failures.6

In the folk sector, healers are non-professional, non-bureaucratic specialists; they have received little or no training in professional medicine.7 Their knowledge of healing often comes from serving as an apprentice to another folk healer; they are viewed as important healers because they have an inborn or special healing power and/or have been the recipient of her or his master’s knowledge. Folk healers are, according to Kleinman, frequently classified into sacred and secular, but these are blurred in practice and usually overlap. Folk healers usually approach healing in a holistic way, dealing with a person’s interactions with the natural and the supernatural realms and with a person’s physical, emotional, and even spiritual problems. They practice herbalism and concoct recipes consisting of plant and animal and mineral substances (hence some are herbalists and root-cutters); they also use traditional surgical and manipulative treatments, recommend special systems of exercise, and advocate “symbolic non-sacred healing” (hence some may be termed shamans). Because of folk healers’ methods and their intermediary position between the popular and professional sectors, professional healers view them with distrust and suspicion (although the feeling is often reciprocal), even as charlatans and quacks who pose a danger to those whom they treat.

The popular sector is non-professional and non-specialist.8 It is at this level where medical problems and ill health are first recognized and defined. The popular sector includes all the healing options that people freely make use of without recourse to folk healers or medical professionals. Most illnesses, as Kleinman points out, are self-diagnosed, and methods for treating them are based on this self-assessment or on the advice of a relative, friend, or neighbor. Healing and treatment may also be carried out in a religious setting or by consulting a layperson possessing special experience or knowledge. As Kleinman argues, the main arena of health care in the popular sector is the family, and it is here where most illnesses (70, even 90, percent)9 are evaluated and treated, usually by women like mothers and grandmothers. The popular sector is usually overlooked in medical literature, but for many cultures this is the predominant form of care and the first therapeutic intervention. This sector also emphasizes prophylaxis or preventative medicine. People learn healthy lifestyles through informants at this level: what foods to eat or to avoid; appropriate levels of drinking, sleeping, working; the role of spirituality; and interpersonal relationships. Even so-called magical means like charms and amulets may constitute acceptable prophylaxis if they can ward off disease or maintain good health.

Sick people, at the individual or family level, make choices about whom in the three sectors they should consult for help if their own self-treatment fails. In some cultures (and, as we will see, this was and is still true for parts of Greece), a person may consult healers from several sectors at the same time; for example, one may seek the help of a doctor while also seeing a priest, especially if the source of the illness is seen by the patient in supernatural terms. Or a patient may act sequentially: after self- or familial help has failed, one may consult a folk healer like a root-cutter and then, if that course of treatment fails, a licensed physician. Ill people will not only choose the sector for treatment, but will even, at times, determine which course of treatment to follow among the options provided by that sector. Many factors go into this decision-making process. A healer in one sector may diagnose or offer therapeutics that seem nonsensical to the patient or run contrary to her expectations, and so the next option may be best. Other deciding factors include the unavailability of a sector (for example, only folk healers may live in the village); a lack of economic means (an inability to pay or travel distances); the (real or imagined) success and reputation of the healer; or the patient’s self-assessment of the problem or the assessment of the problem by others. When an ill person resorts to a folk or a professional healer, the choice is determined by the popular sector. The person self-assesses the problem or uses the assessment of others in his circle (immediate family, extended family, friends, neighborhood, church, etc.), and proceeds to treatment. If that course of action is insufficient, then the patient moves to the folk or professional sector (or even to both simultaneously). After treatment, the patient returns to the popular sector for evaluation and decides if further steps are needed and whether the care has worked and was of quality; that experience, in turn, determines future action when illness recurs. Therefore, the popular sector is the nexus of the boundaries between the other sectors; one enters into, exits from, and interacts with the other two sectors from the popular sector.

The attraction of Kleinman’s theory is that it demonstrates the existence of medical pluralism, and how competing and coexistent medical traditions operate, in a culture. There is a weakness to the model is that categorization is not always so neat; for example, herbalists in a culture may have a professional status, while a midwife may employ Western drugs as quickly as a magical amulet. Moreover, one sector may achieve such a dominant status that the other sectors are marginalized or even proscribed.10 Indeed, in many developed countries, the professional sector is so entrenched that folk healing is viewed as superstitious, irrational nonsense, and the popular sector, with its emphasis on self-assessment and self-treatment, is strongly discouraged (unless done in the context of the professional, such as the dispensing of over-the-counter, sanctioned pharmaceuticals).

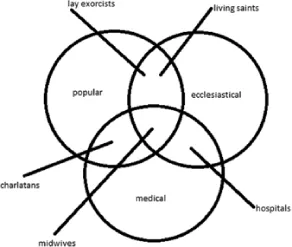

For our purposes in this volume, Kleinman’s model is insufficient in another respect: the religious is a subset of the popular category. Religion, whether the belief-systems of ancient and Hellenistic Greece or the Eastern Orthodox Christianity of Byzantium and post-Byzantium, has always formed an integral part of Greek culture and everyday life. Thus, in a model of medical pluralism, the religious must be accorded a prominent place. Here David Gentilcore’s medical pluralism model for early modern Italy (Healers and Healing) works beautifully. Gentilcore saw in Matthew Ramsey’s model of medical practitioners an absence of religious healing and proposed a Venn diagram that comprises three sectors—medical, ecclesiastical, and popular—to explain medical pluralism for a country (Italy) not dissimilar to Greece:

Figure 1.2 Venn Diagram of Gentilcore’s Medical Pluralism

Like Kleinman, through his model, Gentilcore leads us to see how various forms of medical healing overlap and intersect, and how practitioners of different backgrounds and orientation function in a culture of medical pluralism. For Gentilcore, the medical sphere includes apothecaries, physicians and surgeons, midwives, and itinerant doctors; the ecclesiastical sphere comprises priests, ordained exorcists, living saints, and healing shrines and religious objects (relics, icons, etc.); and the popular sphere “cunning folk.” Gentilcore’s model also allows us to see how activities of a healer in one category may overlap with those in another. Thus, hospitals fit into the intersection of the medical and the ecclesiastical: many monasteries functioned both as a hospital, with physicians and surgeons on staff, and as a place of spirituality, with clergy in residence. The cunning folk of Gentilcore’s study, often village women knowledgeable in health and healing, used religion: prayers, the sign of the cross, and items like holy oil and holy water, in conjunction with herbal concoctions. Their knowledge of remedies came from a shared network, the observation of the properties of local flora, and empiricism.11 A priest may be involved in healing through prayers and rituals, but he could also run an apothecary shop that offered for sale spells that are decided...