![]()

PART I

Listening

Elaine King and Helen M. Prior

The first section of this volume explores our interaction with music through listening. The four chapters are bound together by their empirical approaches, while they also provide scope for a broader understanding of the effects of familiarity on music listening through their diverse settings and scales of approach. Firmly situated in everyday listening habits, Greasley and Lamont (Chapter 1) explore the ways in which listeners’ listening habits change over time, describing the waxing and waning of listeners’ liking for music during a month of normal listening and throughout their lives. In Chapter 2, Prior adopts a more music-specific approach, examining the effects of daily listening to pieces of tonal and atonal music on listeners’ perceptions of those works. Case studies are used to exemplify the development of perceptual cues in listeners’ conceptions of the music and the ways in which these change over a two-week period. The effects of repeated listening to specific pieces of music are also explored by Dobson in Chapter 3, who reports on her study of novice concert-goers and the effects of listening to recordings of concert works prior to a performance. Her fascinating findings point to the complex issues surrounding concert attendance, and situate the examination of the effects of familiarity on our engagement within music in a real-life context with particular contemporary relevance. The section is completed by the examination of the effects of familiarity with music in another real-life setting: that of a post-operative hospital ward (Chapter 4). Finlay reports on some of the qualitative findings of her mixed-methods study examining the use of music as an audio-analgesic. The section as a whole, therefore, provides a picture of the effects of familiarity on our engagement with music as listeners from the small to the large scale; from relatively controlled experimental settings to wholly ecologically valid real-life settings; from popular music to classical; and from listening purely for enjoyment to clinical applications of music. Although there will always be further questions to answer, this section of the book sheds some light on the role familiarity plays in an activity undertaken by the vast majority of those who engage with music.

![]()

Chapter 1

Keeping it Fresh: How Listeners Regulate their own Exposure to Familiar Music

Alinka Greasley and Alexandra Lamont

The purpose of this chapter is to explore current understanding of the ways in which familiarity with music shapes musical preferences and listening behaviour. It has been well documented that our liking for music increases as our familiarity increases, and decreases with repeated exposure (cf. North and Hargreaves 1997). However, most previous studies have based their conclusions on people’s responses to experimenter-chosen music in laboratory conditions over short timeframes, and this explanation is too simplistic. More recent studies employing open-ended methods to explore engagement with music over time (Greasley 2008; Greasley and Lamont 2009; Lamont and Webb 2010) have shown that the process through which music becomes familiar and through which liking/disliking for certain styles of music develops, and the effect that familiarity has on listening behaviour, all vary from person to person and in response to the specific music a person is listening to. Research has thus only just begun to identify some of the key factors shaping the relationship between familiarity with music and subsequent uses of and responses to music. We draw here on literature from a range of music-psychological approaches to address the following questions: how does music become familiar? How do listeners understand the concept of familiar and ‘favourite’ music? How do listeners behave in order to maintain and protect familiarity in music? As well as outlining prevailing theories, we draw on research findings from two of our own recent studies.

Preference, Novelty and Familiarity

The process by which a piece of music becomes familiar is one of the best-theorised in music psychology. Within the framework of experimental aesthetics, different approaches have been formulated to explain listeners’ responses to music. One of the earliest approaches was the mere exposure hypothesis (Zajonc 1968, 1980), which argues that, all other things being equal, exposure will make us like something more. This simple idea has received some empirical support in a range of domains, including music (Colman, Best and Austen 1986; Harrison 1977; North and Hargreaves 1997; Orr and Ohlsson 2001; Peretz, Gaudreau and Bonnel 1998; Sluckin, Hargreaves and Colman 1982, 1983). However, more complex theories have been developed to explain how this process might operate over time and with different kinds of stimuli, familiar as well as novel, and most of these draw inspiration from Berlyne’s psychobiological theory of aesthetic preference.

Berlyne (1971) introduced the notion of arousal potential, arguing that preference results from the interaction between the listener’s level of arousal (relatively stable) and the arousal potential of the music itself (which can vary). Properties of the stimulus that can evoke arousal include psychophysical properties such as loudness or pitch, ecological properties such as associations with positive or negative situations, and collative properties (novelty, complexity and familiarity). Berlyne used the inverted U-shape (or Wundt curve) to illustrate this relationship. Arousal potential (the sum of the above, with most emphasis on the collative properties) determines preference, so stimuli with a moderate level of arousal potential are preferred the most, while lower or higher than moderate levels of arousal potential lead to lower preference judgments.

In Berlyne’s approach, familiarity is linked to complexity, both of which are necessarily subjective for a given listener at any time; as noted above, these are the most important determinants of preference. Much research has supported this theoretical explanation from a range of fields, finding that moderate levels of arousal lead to the highest levels of preference (Hargreaves 1984; Kellaris 1992; North and Hargreaves 1995, 1996b, c; Russell 1986; Schubert 2010). However, particularly in research into visual art, the importance of complexity and familiarity has been overshadowed by other features of the stimuli such as typicality (Martindale, Moore and Borkum 1990) or meaningfulness to the participants (Martindale and Moore 1989). In particular there has been some challenge to the notion of arousal as being too simplistic an explanation when considering complex stimuli like music that can be processed at a deep level (Martindale et al. 1990).

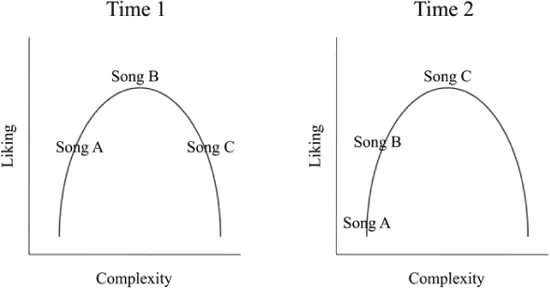

Berlyne’s original approach did not include any explicitly temporal elements of preference, and research exploring its relevance has tended to take a piece of music and a listener at a given moment in time and assess their familiarity and levels of subjective complexity with the music alongside their liking (North and Hargreaves 1996b). However, familiarity is not a static concept. A development of Berlyne’s ideas which attempts to capture this is Walker’s (1973) psychological complexity and preference theory. This combines the principle of optimal complexity (a parameter of the individual) and situational psychological complexity to argue that experience with music alters its subjective complexity: with repeated experience, very complex pieces will be liked more, while very simple pieces will be liked less. This has received some empirical support (Heyduk 1975; Hunter and Schellenberg 2011; North and Hargreaves 1995; Schellenberg, Peretz and Viellard 2008; Szpunar, Schellenberg and Pliner 2004). For example, North and Hargreaves (1995) found that listeners’ tolerance levels remained higher over successive repetitions of more complex music than simpler music. Schellenberg et al. (2008) found that liking ratings followed an inverted U-shape over successive exposures in focused listening situations in the laboratory. However, these studies found that liking when listening was not focused or when distractor tasks were being undertaken followed a more monotonic relationship with exposure. This could be because a lack of attention over such short time-spans does not allow subjective complexity to be reduced.

In more ecologically valid and realistic contexts, music preference has also been found to rise and fall in a similar way to the inverted U-shaped predictions (Russell 1986, 1987). Russell explored chart positions, radio airplay time and preference for current popular music, finding that preference for unfamiliar pieces increases with repeated exposure to a certain point, but then decreases as listeners become satiated with the music. This process of change in subjective complexity over time is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Patterns of changing complexity over time

Source: Hargreaves, North and Tarrant (2006), p. 141.

Russell’s research raises the important question of choice over exposure to stimuli. In the laboratory studies that have dominated research in this field, most stimuli are artificial and exposure is highly controlled. In real-life settings many more factors play a role in shaping experience with naturalistic stimuli. When we can consciously control our degree of exposure to the stimulus, as is the case in most music listening situations, the preference-feedback hypothesis advanced by Sluckin et al. (1983) suggests that the peak of satiation is avoided through a process of self-regulation. By avoiding excessive levels of exposure, the relationship between familiarity/complexity and liking can proceed in a pattern of waxing and waning. This pattern has been demonstrated both in listeners’ nominations of preferred music from different periods (North and Hargreaves 1996a) and in popularity rankings of composers and works over time (North and Hargreaves 2008; Simonton 1997). Music choices are also highly context-dependent (North, Hargreaves and Hargreaves 2004), and greater levels of choice lead to more positive outcomes such as positive mood states (Sloboda, O’Neill and Ivaldi 2001) and lower levels of pain perception (Mitchell, MacDonald and Brodie 2006). This suggests that some concept of choice must be included in research attempting to explore familiarity. Much of the existing research draws on experimenter-chosen music in an attempt to control for factors such as subjective complexity, but by doing so omits important and interesting aspects of musical engagement.

The time course of musical preferences and familiarity as they might operate for an individual over weeks, months and years has not been studied very much at all. Most of the laboratory studies explore a limited number of repetitions within a single experimental session (for example, Szpunar et al. 2004 compare two, eight and 32 repetitions of tone sequences or 15-second extracts of music). Cross-sectional research has suggested that liking varies over the life-span as well as on an individual basis, and some generalisations are possible (cf. Hargreaves, North and Tarrant 2006). For example, younger children are more accepting of different musical styles or are ‘open-eared’; adolescents are much less tolerant; and open-earedness partially rebounds in early adulthood and then declines in older age (LeBlanc 1991; LeBlanc et al. 1993). Complex music seems to be more preferred by older listeners (Hargreaves and Castell 1987), who also tend to report higher liking for classical music and jazz (Hargreaves and North 1999).

Subtle changes in people’s patterns of response to music in the context of everyday music listening have not yet been satisfactorily addressed. How can listeners negotiate a path between their own self-chosen music listening and the music they hear on the radio and through other media when saturation is close? Does liking always decline in the second half of the inverted U, and how much time is required before a piece of music is sufficiently ‘novel’ or complex to permit re-engagement? Finally, how do everyday life situations and the role of listeners themselves, other people in their lives, and their situations, motivations and emotions affect this process? Studies of music in everyday life (Greasley and Lamont 2011; North et al. 2004; Juslin et al. 2008) have begun to map people’s engagement with music across different settings (for example, contexts, activities, social situations) and increasingly account for the role of listener’s personal musical choices (see Sloboda, Lamont and Greasley 2009). Recent studies investigating the influence of emotion on preference have also shown that, the stronger the emotions aroused in a listener, the more likely it is that the piece will be liked (Schubert 2007, 2010). However, these questions have received virtually no consideration in the literature on familiarity thus far, and so in the remainder of this chapter we present some detail of our own empirical investigations into some of these key issues.

Mapping Short-term Patterns of Preference

In our first study (Lamont and Webb 2010), we explored how musical preferences might ebb and flow over the relatively short time period of a month. This exploratory study centred on the relevance of the concept of musical ‘favourites’, asking participants to identify a daily favourite piece of music and exploring the situational factors around this as well as the representativeness of a daily favourite for more stable patterns of listening behaviour. The focus on early adulthood, although partly a matter of convenience, was also because early adulthood has been shown to be a period of consolidation of music preferences (LeBlanc 1991).

Nine participants (three men and six women, mean age 21 years 7 months, drawn from a university population) completed daily listening diaries for a week, followed by a two-week gap, and then again for another week. Only one participant was receiving musical training, but four others had learned instruments in childhood. The daily structured diaries were based on existing experience sampling research (Sloboda et al. 2001) and asked participants about key events in the day. This included nominating one favourite piece of music per day, with contextual information about whether that piece had been heard and if so whether it was through choice, for what purpose, and why. The purpose of the daily diary was to explore the face validity of identifying favourite pieces as a way into people’s fluctuating patterns of involvement with music over time.

Each participant nominated at least two different favourite pieces of music over the course of the two weeks, with the average being six, although some nominated more than 14 in total (having chosen more than one on a particular day). The music chosen was very diverse, including contemporary pop (Christina Aguilera, Take That), older pop (The Cure, The Smiths), rock (Dire Straits, Eric Clapton, Led Zeppelin) and classical (Verdi, Pachelbel). Despite the homogeneity of the sample in terms of age, occupation and social environments (many were friends and four lived together), only 5 per cent of the nominations overlapped. This provided strong evidence for the unique nature of preferences and listening habits.

Almost all the favourite pieces were heard on the day in question, with just under two-thirds (61 per cent) being actively and deliberately chosen and a further 17 per cent being chosen through less explicit mechanisms (listening to the radio and shuffle mode on iPods). The data does not allow us to identify where the concept of the favourite begins: it is possible that participants have a favourite piece of music in mind and choose to listen to it, or conversely they may choose to listen to music they like and one of those pieces happens to ‘stick’ as a daily favourite. However, it does suggest that most memorable listening experiences are self-chosen and have a relationship to this concept of a daily favourite. It also gives some indication of the stability of this relationship: looking over the two weeks, purely random hearings of music that were nominated as a daily favourite were never repeated for the same participant, whereas deliberately chosen music appeared much more frequently in their weekly catalogues of favourites. Looking at the data when nominations were not heard on the day, although this only reflected a small number of the total data points, non-heard favourites were often in people’s heads because they had been recently heard; out of...