![]() Encounters with Other Christian Denominations

Encounters with Other Christian Denominations![]()

Chapter 3

Double-Identity Churches on the Greek Islands under the Venetians: Orthodox and Catholics Sharing Churches (Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries)

Eftichia Arvaniti

‘Shared churches’ or ‘churches of double usage’ emerged among Orthodox and Catholic flocks in areas of Greece under Venetian domination from the thirteenth to the eighteenth centuries. In these churches both Catholic and Orthodox rites were celebrated, regularly or on occasions, on the same altar or on two different ones.

As this chapter shows, the double usage of Catholic or Orthodox churches and the embracing of different religious practices and new principal religious figures (saints, priests, monks) were reported by visitors on the Greek islands from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Some of these churches can still be seen today. Why did outsiders – i.e., visitors, heads and emissaries of the two Churches and of the Venetian State – report and repeatedly refer to such practices in their correspondence? Because they were innovative in their eyes, thus, awakening feelings – negative or positive, depending on their perspective. After all, it is ‘the perspective from which we choose to measure the novelty of a phenomenon’ (Williams, Cox and Jaffee 1992: 3) that determines whether it is evaluated as a positive innovation or as a disturbing change.

In this chapter I will examine shared- or double-identity churches and more specifically highlight the: (a) reasons behind such innovative practices; (b) actual innovative elements in the architecture and art, indicating a parallel usage of the churches by both Orthodox and Catholics living in the Greek islands under Venetian domination; and (c) related religious practices in and around these churches.

Historical Background

The Venetian presence on many Greek islands from 1204 to the sixteenth century – and in some cases up to the eighteenth century – shaped the religious history and identity of the local population. The tolerant attitude of the Venetian policy towards religion contributed to a long peaceful coexistence of the two confessions that lasted on some islands for almost four centuries. After 1400 and by the sixteenth century, both Venice and the Pope supported the autonomy of the Orthodox practices (Pangratis 2009: 29–37). The Apostolic Visitator A. Bernardo reported in 1652: ‘not only in the above mentioned Greek churches but, according to the circumstances, also in all the other churches the Latins celebrated freely’.1

Because under Venetian rule Orthodox clerics were placed under the authority of the Catholic Church, there was only one Catholic bishop on the islands. The Catholic bishop appointed a Greek Archpriest (Protopapás) as the head of the Orthodox clerics.2

From the reports of Catholic bishops and papal emissaries we see how the Catholic Church perceived the Orthodox as ‘Catholics of the Greek rite’,3 as a consequence of the union at the Ferrara-Florence synod (1439).4 Both the Pope and Venice knew that the synod was not viewed as valid by the Orthodox, but it strengthened their political and social influence on the Greek islands to some degree. They both used the Ferrara-Florence union as an excuse when reports from the Greek islands referred to repeated shared practices of sacraments, such as confession, or even the bilateral baptism and confirmation. Especially after the beginning of the seventeenth century and the establishment of the Propaganda Fide,5 interesting religious practices and customs developed on the islands, for example the right of Catholic missionaries to preach to the Orthodox population and to hear confessions.6 At the same time, Orthodox customs – such as the rituals of memorials (mnimósinon),7 the ordinary leavened bread (andídoron)8 and the physical veneration of icons – were adopted by the Catholics. Finally, mixed (inter-Church) marriages made things even more complex as the two flocks became more connected with each other.

In 1775 Cardinal Andrea Corsini detected different types of Orthodox believers on the island of Tinos:

a. the purely Orthodox;

b. those who lived in Catholic villages and went to Catholic churches on a daily basis, but once a year during Easter they went to an Orthodox parish somewhere else;

c. those who lived in mixed villages and went to various churches;

d. those who often went to Catholic churches, but never dared convert out of fear or shame.9

We can observe analogous behaviour and categories of Catholics on most islands under Venetian rule.

The Motivations behind the Shared Churches and Religious Practices

What were the reasons for the attraction of both religious groups to the other’s churches and religious practices even after the end of Venetian rule on the islands? Syncretism10 could not be the only explanation of this complex phenomenon in view of the variety of practices and deliberate modifications of the church buildings, as outlined below. Having two aisles (or parts) and two sanctuaries offered a systematic flexibility11 accompanied by an interior decoration that underlined the double identity of these shared churches.

At first, the reason, must have been the obligation (belonging to the Catholic Church and being under Venetian rule) of both Orthodox and Catholics to celebrate together at specific times. The subordination of the Orthodox bishop to the Catholic bishop meant that the latter had the power to intervene in religious matters, such as requesting a Catholic altar inside important churches, especially those with miraculous icons or relics. Such churches were great attraction points for both flocks. Later on, mixed marriages often produced bi-confessional families, who wanted to celebrate major feasts – like Easter – together and be buried together. Private chapels of mixed families demonstrated both their religious devotion and need for togetherness.

Long distances, in combination with a lack of priests (mainly Catholics) on many islands, forced small religious communities to employ the ‘others’ for their religious needs.12 Using the closest parish – even of a different confession – was a matter of convenience, not only for the inhabitants of the islands, but also for travellers (in the case of churches located next to ports or passages). Finally, rituals on feast days celebrating specific saints were very common and chiefly a social event for these island communities.

The Architectural Innovations in Shared Churches

The Venetians took control of Byzantine cathedrals and many important churches from the beginning of their rule. Common participation in official ceremonies mainly determined the linking of the two religious groups (Papadaki 1995; Nikiforou 1999). In order to have an intermingling of cultures in religious rituals during the annual Venetian festivities, as intended by Venice, the entire local population and clergy were ordered under penalty of law to take part in the processions and celebrations.13 In all major churches of the islands (cathedrals, ancient monasteries, Protopapás’ [Archpriests’] churches), both religious groups celebrated important festivities at separate altars within the same church.

Modifications of the Sanctuaries

The Orthodox had their own space inside major cathedrals, as indicated by the examples of St Titus in Candia (Hemmerdinger-Iliadou 1967: 580) or Santa Maria Maggiore (–1443), alias San Marco (–1623) alias St Sophia (–1715), in the Kastron of Tinos. Catholics had their own altar in the only Orthodox church – also in the Protopapás’ church in Aghia Paraskevi, also in Kastron in Tinos. All reports by bishops and papal emissaries speak of a second Catholic altar, devoted to the same saint (Santa Veneranda).14 On Santorini, in the village of Pyrgos, there was no Catholic church so the Catholic community preserved an altar inside the Orthodox Cathedral of the Virgin. It was built by Duke Domenico Crispo, who donated it to both religious groups after his death.15 The Byzantine church of the Virgin of Episkopi on the same island had two Catholic altars, where Catholic bishops held weekly masses.16 Likewise, in the early Byzantine church of Katapoliani, in the port of Paros, from the beginning of the Venetian rule Catholics preserved their own altar, which was dedicated to the Virgin, St Francis and St Anton of Padua; it was renovated during the War of Crete and preserved until the end of the eighteenth century.17

Separate altars were also reported in private churches (ius patronatus privato).18 The traveller Coronelli mentions that Duca Gerolamo Lippomano erected a Catholic altar inside the Orthodox chapel of Saint Nicholas in Candia. Also, Apostolic Visitator Giustiniani refers in 1701 to the church of the Nativity of the Virgin in Kontohori of Santorini: ‘Dug in underground … there are two altars, one for the Greeks and the other for the Latins’ (Hofmann 1941: 96).

Around 1670 a Catholic altar was erected as a votive chapel inside the Orthodox church called Sto Kóma in the port of Faros, in Sifnos, by a pirate captain, Giovanni Maria Cardi, who also donated 100 Realli for holding masses in this church.19 This church is today’s Panaghía Hrysopighí, nowadays a monastery with a miraculous icon (Zoodóhos Pighí Assumption). ‘An ancient and miraculous icon’ is also mentioned by the Catholic Bishop of Zakynthos, Baldassar Maria Remondini, in his description of the church of Panaghía in the Kastron of Kythira,20 where several festivities took place in honour of Panaghía Myrtidiótissa. The Orthodox often celebrated masses on the Catholic altar of this church in order to venerate that icon (Panaghiota 2003: 453).

In 1627 the Proveditor21 of Candia, Francesco Morosini, reports on the church of the Catholic bishop in Kato Episkopi, near Sitia: ‘In the town of Kato Episkopi I saw a Latin church, where the Greeks also celebrated frequently, with the mutual satisfaction and joy of one and the other rite.’22

The church is apparently Byzantine (probably tenth century; Gallas 1983: 269) and is dedicated to the Holy Apostles and St John. Its only altar is attached to a small niche in the eastern wall, which is flat on the outside.

These flat eastern sanctuary walls are today key features indicating Catholic churches in larger island towns, where more Catholics lived.23 Many such churches even have small niches inside and only a flat wall on the outside;24 however, the size of the niche is only a marginal criterion of the Catholic presence in a church. Moreover, in the Catholic archives of Tinos we observe the following: Catholics started systematically building up the niches of the sanctuaries to flat walls, following the establishment of the Orthodox See there (1715) and the decisions of both Churches to prohibit common rituals (1748, 1757).25 This was a manifestation of the confession of the church on the exterior of the building.

Whether a church had a Catholic or an Orthodox exterior ‘appearance’ was important, as we see in the case of the monastery of Aghios Athanasios in Naousa, Paros (today an icon museum), which was sold in 1675 to the Catholic community. They demolished the sanctuary (‘being a Greek church’), detached the iconostasis (‘as it was closing the sanctuary’) and put the icon of the saint in the middle of the altar (‘according to the customs of the Catholics’; Zerlendis 1922: 68).

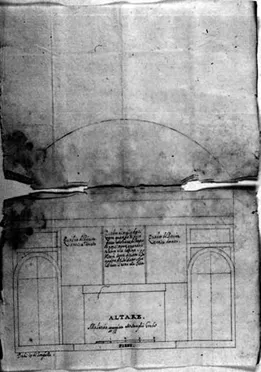

These acts of Catholic manifestation were more important and possibly frequent in areas with sizeable Catholic and Orthodox communities, and especially in shared churches with two separate aisles and two separate sanctuaries. The flat wall of one sanctuary in the two-aisled church of Aghios Gheorghios in Htikados, Tinos, is a fine example (Figure 3.1). The double usage of the church can already be seen in its exterior: two aisles with two sanctuaries, one ending in a flat eastern wall; two entrances – one in the west, the other in the south; and even two belfries, one over each door.

Apart from separate main entrances, side openings were also necessary for shared churches in order to prevent disorder in the coming and leaving of clerics and believers, or even theft and vandalism.26 To support the symbiosis of

Figure 3.1 Aghios Gheorghios, Htikados, Tinos: a. east side; b. north side

Figure 3.2 Plan of the doors flanking the sanctuary of the church of Afendis Christos in Ierapetra, Crete. ASV, Provveditori da Terra e da Mar, b. 786

the Orthodox and the Franciscans in the church of Afendis Christos in Ierapetra, Cret...