![]() PART 1

PART 1

Theoretical Foundations![]()

Chapter 1

Realism in the Sociology of Education: ‘Explaining’ Social Differences in Attainment

Introduction

Realist approaches to sociology have been stimulated by recent works, of which the rigorous investigations by Bunge (1979) and Archer (1995) have been particularly influential, in the philosophy of science and social theory. The sociology of education, by no means the least important area for the practice of sociology, may stand to benefit from these attempts to reposition the nature of sociological enquiry and explanation. This chapter will seek to explore some implications of realism for the sociology of education in the context of a presentation of empirical findings from a New Zealand research programme. Two large-scale projects carried out in the last ten years, Access and Opportunity in Education (Nash, 1993a) and Progress at School (Nash and Harker, 1998), have attempted to develop an integrated approach to the investigation of socially differentiated access to education constructed around a ‘family resource framework’ informed by realist theses, and data from the second of these will be presented in some detail. Although basically constructed with reference to Bourdieu’s (1977) analyses of social and educational reproduction, and strongly influenced by his methodology, several characteristics of Bourdieu’s theory, particularly its functionalism and relativist epistemology, are rejected, and it would consequently be misleading to position our research programme as ‘Bourdieusian’. In fact, the immediate problem for research with statistical data is to analyse it in the most appropriate and informative manner, but that is an issue requiring more discussion than is sometimes offered, and the influence of Bourdieu’s work in this respect is not uniquely problematic. Bourdieu’s theory of educational inequality is related only indirectly to methods of statistical enquiry and, while engaged with correspondence analysis, it is not dependent on any specific technique and lends its support to no particular form, but as much cannot be said for all theoretical approaches. On the contrary, in the structural models of ‘causal sociology’, based on correlational methods and employed with considerable effect by Jencks et al. (1972), the analytical technique has a dominant position in the construction of theoretical accounts, and in Boudon’s (1981) theory of socially differentiated access to education flow models in the form of tables have a similarly important role. The techniques of statistical analysis and the forms of explanation associated with them, in fact, require to be examined in the context of an enquiry directed to the nature of the relationship that exists between them. Inspired, therefore, by a search for realism in sociological accounts of educational inequality, the following discussion will examine the approaches of Jencks, Boudon and Bourdieu to statistical data with specific reference to an empirical study concerned, above all, to discover the answer to a real problem: What are the main causes of social differences in educational attainment?

The Progress at School Project

The data discussed in this chapter are from the Progress at School project, which followed the educational careers of 5,384 students who entered 37 New Zealand secondary schools in 1991: this is virtually a 10-per-cent sample of the annual cohort. In New Zealand students enter secondary school in the third form (Year 8) when they are usually 13 or 14 years of age, and may leave at age 16, but most complete sixth form (Year 11) and a considerable minority remain to seventh form. The research was designed as a school effects study (Smith and Tomlinson, 1989), but few differences in students’ attainment that could be attributed to any property of the school attended were observed, and the data are examined here with other interests in mind. Student attainment was assessed at five points: at third-form entry by New Zealand standardised tests of reading and ‘scholastic ability’ (IQ); at the completion of fourth form by specially designed tests of English, mathematics and science; at fifth form by results in the nationally assessed School Certificate examination; at sixth form by results in the nationally monitored Sixth Form Certificate award; and at seventh form by the nationally assessed University Bursary examination.

Correlational Models: Jencks

In many respects the Progress at School data set is comparable to those used by Jencks et al. in their influential study Inequality. Jencks’s team set out to report the extent of educational and income inequality in American society and investigate its causes: their investigation remains a classic example of orthodox quantitative methodology in the sociology of education and provides an appropriate starting point. The object of correlational analysis, of which path analysis is an advanced form, is to estimate the relative degree of influence of the several variables included in the analysis by discovering the amount of variance ‘explained’ by each. When Jencks et al. (1972: 139) state, in a proposition entirely representative of this form of argument, that ‘about a third of the discrepancy between economically advantaged and disadvantaged students is explained by differences in their test scores’, a statement of causality is made that is based on nothing more than a ‘descriptive presentation’ of certain relationships that exist in the data. When information is collected on students’ test scores and their parents’ occupations it is invariably observed, if the sample is representative and of adequate size, that students from richer homes are more likely to have higher scores than those from poorer homes. The degree of association between the two variables can be expressed by a correlation coefficient. If, for example, the correlation between social class and test score is about 0.35 (a value typical of the association between IQ-type tests and scales of socio-economic status), then it is consequently established that about 12 per cent of the variance in each set of scores is shared with the other set and, by a long-standing convention, it is said that 12 per cent of the variance has been explained. In this instance, as children’s IQ is obviously not a cause of their parents’ class position, it must be that 12 per cent of the variance in the intelligence of children is due to their social origin. As a result of analysing data from several US studies available at the time of their investigation Jencks et al. conclude that 30–35 per cent of the variance in academic attainment between economic groups is due to differences in their IQ test scores, and suggests that about a third of that proportion is due to the capacity of the most economically advantaged groups to donate superior genes to their offspring, and that two-thirds is due to their competence to develop valued cognitive skills.

Multivariate path analysis is a very powerful technique for examining the relationships between numerical data, and theoretical accounts derived from causal modelling are, at least, more credible than those based on research that avoids quantitative analysis in favour of ‘qualitative’ observations that, insofar as they rely on what Lazarsfeld (1993) has all too easily castigated as ‘impressionistic quasi-statistics’, are dismissed without difficulty by those aware of the relationships that actually exist between variables. The Progress at School project made the fullest use of quantitative techniques (Harker and Nash, 1996), including hierarchical linear modelling (Goldstein, 1987), and there is no intention to disparage their value. Nevertheless, the title ‘causal sociology’ is a polite fiction and it is sometimes necessary to insist that associations between data are not causes and cannot be declared to be so by fiat. All introductions to ‘causal modelling’ in statistical sociology emphasise in their earliest pages the crucial distinction between genuine causal correlations and contingent correlations but, nevertheless, maintain a formal commitment to a Humean causality in which that distinction cannot be acknowledged. The formal claim, after all, is that if variables are associated they are correlated and that if they are correlated their shared variance is ‘explained’. In this way the language of causal relations has become a deeply embedded convention of the field with a definite influence on the forms of substantive explanation developed. Of course, the idea that ‘constant conjunctions’ demonstrated by correlations represent real relations of causality is not taken seriously, and a large amount of creative energy is actually devoted to devising post-hoc explanatory accounts of the concrete social processes responsible for the generation of observed patterns of associations, but it is in this fashion that ‘causal sociology’ makes a somewhat illegitimate homage to realist sociology, in which a theory of the causes of a social event, process or phenomenon must gain its substantive explanatory power from its ability to model the mechanism by which it is brought into being.

That associations are not, in fact, explanations, is uncontested, and the term ‘variance explained’ is, in that sense, one that begs the question, but in the case of many associations the possibility of a genuine relationship of causality is not easily dismissed. Children’s test scores cannot determine parental income, but the idea that the prosperity of a family is a partial cause of its children’s intellectual development is a great deal more plausible. The substantive theoretical argument constructed around statistical models necessarily depends, in fact, on an appeal to ‘reasonableness’ and ‘plausibility’. In his account of why students from the middle-class rather than the working-class are more likely to leave the educational system with higher qualifications Jencks et al. (1972: 138) argues, for example, that ‘they are more likely to have genes that facilitate success in school’, ‘more likely to have a home environment in which they acquire the intellectual skills they need to do well in school’, more likely to ‘feel that they ought to stay in school, even if they have no special aptitude for academic work and dislike school life’ and, finally, ‘may attend better schools, which induce them to go to college rather than drop out’. Jencks et al. make an attempt to calculate the degree of effect due to each of these variables, but the suspicion that there is little more than an informed common sense at work in the construction of this explanatory sociological account is hard to shake off.

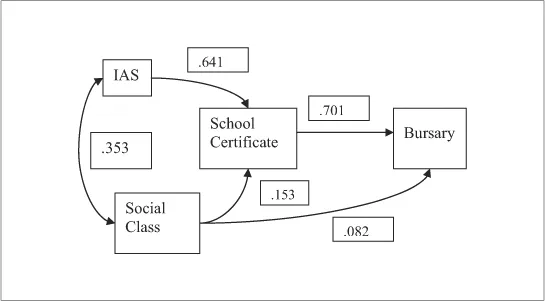

In the light of this discussion, and that to follow, it will be helpful to examine Figure 1.1, which presents the pattern of associations between four variables from the Progress at School data – social class, third form ability, School Certificate and Bursary attainment – in the form of a path analysis. The beta weights expresses the associations between the variables included in the model in a standardised form, and in the language favoured by ‘causal sociology’ the model indicates that prior ability (which many commentators would have no difficulty in recognising as ‘IQ’) has, by comparison with social class, by far the most significant causal effect on School Certificate attainment. Bursary attainment, in its turn, is overwhelmingly determined by School Certificate performance and only to a very slight independent degree by social class. There is probably no escape from the conclusion that third-form ability must have a major role in any convincing model of fifth-form and seventh-form school attainment, and some implications of that will be faced, but it may first be worth looking a little more closely at the data before reaching the conclusion that social class has no more than a trivial effect on secondary school performance once ability has been controlled.

Figure 1.1 Path analysis showing associations between variables affecting bursary attainment

Note: The model shows the beta weights between social class; Intake Ability Score (IAS) based on responses to two standardised instruments, the Progressive Attainment Test (Reading Comprehension) and the Test of Scholastic Abilities, produced by the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (Reid and Elley, 1991; Reid et al., 1981); the principal component from a factor analysis of marks in English, mathematics and science in these three core subjects in the national fifth-form School Certificate examination; and total mark in the seventh-form University Bursary examination. The model indicates that IAS is strongly associated with School Certificate (accounting for 44.1 per cent of the variance) and that social class is only weakly associated (accounting for 2.3 per cent of the variance). It further indicates that IAS has no additional effect on Bursary attainment once School Certificate attainment is controlled, and that social class makes only a negligible additional direct contribution. The total effect, direct and indirect, of social class on Bursary attainment can be calculated as 0.348.

It is not surprising that the criticisms of ‘causal modelling’ rehearsed above are likely to be shrugged off by exponents of this methodology. Their technical terminology rarely misleads them, their positivist concept of causality is a matter of form, and they can be confident that their research is based on empirical data and analytical procedures open to independent scrutiny. Critics who reject the statement that the correlation of students’ IQ with their parents’ social class ‘explains’ a little more than 12 per cent of the variance in IQ must nevertheless account for a correlation of about 0.35 between those variables, and face the unavoidable conclusion that secondary school attainment, over a five-year period, is far more strongly associated with earlier attainment than social class. It is the failure to do that, of course, on the part of so many sociologists of education that is responsible for the great division between so called ‘quantitative’ and ‘qualitative’ analysts (Nash, 1998a).

Tabular Flow Models: Boudon

Perhaps the most informed critique, that of a knowledgeable insider, of correlational analysis and its assumptions has been provided by Boudon (1981). The Logic of Social Action expresses reservations about the explanatory logic of correlational analysis, which, in Boudon’s view, appears to disguise significant relationships apparent in tabular presentations of data, and specifically criticises the syntax of explanation supported by the path-analytic models of so-called causal sociology. In order to explain the correlation between class position and educational achievement it is necessary, he maintains, to abandon the schema that suggests that a series of factors interpose themselves between class and educational success with a cumulative effect depending upon their variable weights. In effect, Boudon thus relinquishes the attempt to estimate the contributions of different variables (rendering problematic their very name) on which quantitative sociology is founded. These ‘factorial’ models, he proposes, should be replaced with ‘decision-making’ models, in which agents with different social origins are recognised as likely to find in their class position a point of reference from which the advantages and disadvantages of deciding on one educational course or career rather than another are taken into account.

In Boudon’s methodological individualism a social phenomenon is only given a satisfactory explanation when what people actually did to bring about that phenomenon is described in such a way that their behaviour, situated within deterministic institutional and social contexts, can be understood with reference to their intentional actions as individuals. This ‘action reference’ requires an act of understanding on the part of the observer. Boudon’s concept of sociological explanation, in fact, follows Weber in making sociological explanations dependent on the intelligibility of action descriptions and supports a discourse in which statistical data and ‘interpretative techniques’ are regarded as ‘complementary rather than opposed’ (Boudon, 1981: 147). His observation that ‘the description of another’s actions proposed by the researcher is only really satisfactory when he can convince his reader that, in the same circumstances, he would have acted in the same way’ (ibid. 145–6) thus places the test of sociological explanation on the capacity of the ‘reader’ to understand the purposes of those whose collective actions brought about, directly or indirectly, the event or phenomenon under examination. In this manner, Boudon continues: ‘one understands that a poor family is more hesitant to take a risk. I understand that relation in the sense that I have hardly any trouble in believing that, in an analogous situation, I would certainly experience the same hesitations’. One might think that poor families would behave in this way, if they do, whether Boudon understood their actions or not, and the capacity of others to understand or accept an explanation cannot be made a condition of its soundness. The Weberian insistence that social processes are explained when they are understood negates the value of any attempt to specify the distinguishing character of sociological explanation.

Boudon’s methodological individualism is unabashedly reductionist: ‘[t]o explain that phenomenon [an observed association presented in a table or represented by a correlation], it must be reduced to the consequences of actions carried out by the agents of the system in question’ (Boudon, 1981: 144–5). The emphasis in that sentence is placed by its author on ‘explain’, but it would go equally well on ‘reduced’. Sociological explanations that insist on the reality of the social, even while refusing to embrace all that is sometimes implied by ‘methodological individualism’ and rejecting a ‘deterministic’ concept of social structure, can accept the general thrust of this argument. In realist sociological accounts, social class is a structural cause of social differences in educational attainment, but any explanation that failed to outline the mechanisms of the social processes by which differential attainment was generated would, at the very least, be incomplete. This is not a matter of explanatory ‘reduction’, and it is necessary to address the supposition that accounts of social events, processes and phenomena in terms of the causal powers of social structures, which are held to be paradigmatic of sociological explanations, are rendered superfluous by the ’reductionist’ accounts of ‘methodological individualism’. One might with more reason argue that without a concept of social structure – the structures of, for example, class position, the distribution of educational qualifications, and access to further education and employment – that the actions of individuals, whether more or less intentional or habit-directed, whose lives are bounded by such real structures could not be explained. It is evident, nevertheless, that methodological individualists prefer to concentrate on rational action, or at least on intentionalist action, rather than on social structures and how people are influenced by them. Far more attention is paid in this field to modelling decisions within the assumptions of game theory than to the examination of social structures and their effects on human practice.

Boudon’s interest in decision-making is, in fact, situated within a sociological framework more often criticised for its normative and ‘over-socialised’ view of the social actor. Thus, Boudon can argue, as is consistent with a concept of ‘deterministic’ structures, that: ‘[c]onfronted with a choice the “social” agent, homo sociologicus, can, in certain cases, do, not what he prefers, but what habit, internalised values, and, more generally, diverse ethical, cognitive and gestural conditionings, force him to do’ (1981: 156). Dahrendorf’s (1968) concept of homo sociologicus was introduced to give normative, role-theoretic, sociology a socially determined model actor distinct from the homo oeconomicus of economic theory. Yet the presence of society, notwithstanding the theoretical language of structural determinism and the uneasy recognition of social conditioning ...