![]()

1 The long journey to libraries of light

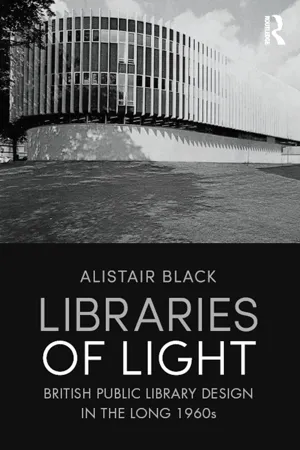

The ‘libraries of light’ described and discussed in this book were the result of centuries of progress in the physical illumination of library space and, through the books libraries provided, in intellectual enlightenment also. Effectively, Sixties libraries were the culmination of a three-hundred-year journey, across the age of modernity, from darkness and shadow to openness and light.

The welfare-state public library and its Enlightenment roots

The journey towards Sixties ‘libraries of light’ originated in the Enlightenment. Summed up by the challenge ‘dare to know’, and encompassing the aim of banishing fear, ignorance and superstition by means of reason and ‘scientific’ knowledge, the term ‘Enlightenment’ stands for the idea of a ‘new sense of a light flooding into hitherto darkened places’.1 Light provides the means to ‘see’ which, as a metaphor for understanding, places it at the heart of modernity.2 The intellectual developments and changed attitude of mind which the Enlightenment brought moulded the principles that informed the post-war, welfare-state public library. They also created a new template for library design which found its most radical expression in the light-rich, open-plan modernist libraries of the long 1960s.

In the era of the welfare-state public library, the provision of books and associated cultural activities grew sharply and a new ethos of service appeared. The period also witnessed a large programme of renewal in the physical infrastructure of the public library system. Contemplating the pre-1960 history of public libraries, the Library Association’s review of new library buildings for 1973–1974 declared that: ‘Too many monumental white elephants litter our towns and cities’; but, the review continued, times had changed, and in evaluating the buildings of the 1960s and early 1970s it suggested that this period ‘may well prove to be something of a golden era of library buildings to rival that which led … to Carnegie libraries, which must at that time have seemed miraculous’.3

Public libraries became an integral part of the welfare state. A 1960s text promoting careers in librarianship noted:

Just as the idea that a citizen has a right to security, health and a livelihood has developed into the present ‘welfare state,’ so the idea that man also needs sustenance for the mind has developed into the intellectual welfare state in which the public-library system plays an important role.4

The welfare-state credentials of the Sixties public library were underlined by the frequent associations made at the time with the flagship of the welfare state, the National Health Service (NHS). The public library was often metaphorically described as ‘an NHS of the mind’, an image which built on the long-standing mantra that a library was the ‘dispensary for the healing of the soul’,5 and which continues to be broadcast today.6

The road to the welfare state that so nurtured public libraries after the war, in terms of both their purpose and physical form, can be traced back – albeit in a line that in places is inevitably crooked and discontinuous – to the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. Libraries first appeared in antiquity, but what one can call the ‘modern’ library, exhibiting an ethos of progress linked to self-realisation and rational discovery, is a product of the Enlightenment. In the eighteenth century, alongside libraries embedded in historic educational and ecclesiastical institutions, social libraries, both the commercial and subscription kinds, became one of the major, sacred spaces of modernity and a core element in what is now referred to as the ‘Habermasian public sphere’.7 Providing an open marketplace for ideas, public-sphere libraries were institutions of ‘democratic communication’ and a ‘public good’.8 The ethos of public-sphere libraries was founded on the philosophical and political principles of the European Enlightenment which emphasised the link between improvement and progress and the ‘scientific’ investigation of nature and society. The ultimate purpose of such libraries was summed up in the opening paragraph of a late-seventeenth-century pamphlet promoting the library movement in Scotland, An Overture for Founding and Maintaining of Bibliothecks in Every Paroch Throughout the Kingdom (1699):

It is as essential to the nature of Mankind to be desirous of Knowledge as it is for them to be rational Creatures, for we see no other end or use for our Reason but to seek out and search for Knowledge of all these things of which we are Ignorant.9

Over a century and a half the public library has continued this noble tradition, coming to embody the principles of human rights, liberty, equality and freedom of thought, expression and association.10 We can frame the contribution of public libraries to society in Enlightenment thinking. Since its inception in the middle of the nineteenth century, the municipal public library in Britain has developed as part of a social policy infused with Enlightenment principles, both idealist-rational and utilitarian-empirical.11 Public libraries have been public goods that epitomise the public sphere. They have been defined by selfless service on the part of the professionals who run them and by geographical and social universality. Their identity is that of a safe public place (or public square) insulated from the logic of the market and welcoming of free and critical expression.12

In order to establish the precise nature of the relationship between the public library and the welfare state it is important to establish the latter’s philosophical origins. The lineage of the welfare state flows back through liberalism and socialism, both of which emerged out of Enlightenment thinking and shared certain beliefs and assumptions about social and economic progress, such as the importance of providing ‘security’ for individuals and increasing their opportunities. In Britain, liberal philosophy was imbued with political power from the middle of the nineteenth century. Characterised in a schizoid fashion by both laissez-faire principles and social reform (the latter seeping into social conservatism), liberalism constructed the foundations of the welfare state in a series of reforms in the decade preceding the First World War, including old age pensions, national insurance and free school meals. A generation later, it was a liberal intellectual, William Beveridge, who built on these foundations and, in his famous report in the Second World War,13 helped pave the way towards a fully fledged post-war welfare state, the contours of which eventually stretched well beyond the mere provision of welfare, reaching up into the heights of economic management and even education and culture, including public libraries. By contrast, socialist thought in Britain – infused with Marxism but driven largely by a pragmatic, trade-union-led struggle for improved worker rights, wages and conditions – did not achieve significant political influence for three-quarters of a century after liberalism’s rise to power. Arguably, however, it made the larger contribution to the establishment of the post-war welfare state.14

Although agreeing on the need for social progress and emancipation, liberalism and socialism grated against each other on many issues, including the redistribution of wealth and the ownership of means of production. They also diverged regarding the motivation behind support for the welfare state, liberals seeing social reform as a means of dampening discontent and improving the imperial race, socialists preaching a discourse of innate rights to a life free from poverty and oppression. These differences aside, however, in the micro-realm of the public library there was a strong tradition of liberal–socialist consensus. Politically, the public library in Britain has been, enduringly, a liberal–socialist, or Lib–Lab, project.

It was this ideological anchorage which gave the post-war public library, once economic conditions had improved, such a secure position in British social and cultural life. Because the welfare state found its ‘condition of possibility’ essentially in the ‘egalitarian vocation’ of Enlightenment thinking,15 the welfare-state public library, imbued as it was with an ethos – if not necessarily always a heritage – of equality of access, was able to thrive in a post-war world that promised a fairer distribution of wealth and power. Underpinning post-war public library philosophy, notwithstanding the suspicions expressed by some of the ‘planning’ and centralised aspects of the welfare state, was the public-sphere notion of the informed, critical citizen, the absence of which in various European societies had led to interwar authoritarianism and, ultimately, to war. The notion of the critical citizen was at the heart of Enlightenment thought. In asking ‘What is Enlightenment’, Kant, in 1784, explained that the more people engaged in literacy, the more ‘mature’ they became. Enlightenment, he wrote, helped humanity ‘exit from its self-incurred immaturity [my emphasis]’, which he defined as the inability to make use of one’s understanding without the guidance of another. ‘Immaturity’, said Kant, was the ‘state under which dependent vassals lived’, whereas independent thinkers were the basis of a free society. ‘Have the courage to use your own understanding’ was for Kant the motto of the Enlightenment.16

Although it is true that as the twentieth century progressed society’s critical function came under pressure from a political public sphere increasingly reliant on public relations (or, to use the modern vernacular, spin),17 it can be argued that the war, and the welfare state to which it gave rise, strengthened social criticism and encouraged free thought, thereby delivering, in Enlightenment vocabulary, ‘a larger number of voices jostling to be heard’.18 This change of social tone was reflected in the librarian Lionel McColvin’s wartime report on the condition and future of the public library system in Britain, in which he promoted libraries as ‘a great instrument and bulwark of democracy’. Civilisation and free access to books, both of which the Axis powers had abandoned, were, in McColvin’s view, closely intertwined. Books and libraries, said McColvin, were essential to the ‘real democratic conditions of living’; they were ‘the tools and the symbols of true freedom’.19 Marking the centenary of the public library in 1950, McColvin also celebrated the fact that Britain had kept its libraries ‘free from any kind of bias or ulterior motive’, maintaining them as ‘a free opportunity and thus hospitable to all varieties of creed and opinion’.20 For J.H. Wellard, another librarian writing at about the same time, the significance of the public library, which he believed had come of age in the war, was in its ‘contribution to the general welfare of democracy’. In common with the free church, free school and free press, public libraries were ‘the instruments of those democratic ideas which Fascism abhors’. The ‘ultimate work’ of libraries, wrote Wellard, was ‘making free knowledge available to free men’.21 In the same vein, the architect E.H. Ashburner (who in the 1930s had designed Huddersfield Public Library and had also been heavily involved in designing Sheffield Central Library) proclaimed the public library to be the ‘university of a democratic people’. The proper functioning of a democracy, he argued, depende...