- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rural Sustainable Development in the Knowledge Society

About this book

Based on the EU-funded CORASON research project, this volume brings together and compares studies into rural and sustainable development processes in 12 European countries. In doing so, it identifies key trends and reveals the changing nature of development processes on the way towards a knowledge society. The book examines the differences between the preconditions and contexts relevant to rural development strategies and those relevant to sustainable development strategies. It explores whether the concept, goals and nature of rural development is better understood and adopted by rural actors than those of sustainable development. Finally by focusing on the ideas and practices of sustainable resource management- a component in both rural and sustainable development objectives- it links with knowledge used by actors involved in rural development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rural Sustainable Development in the Knowledge Society by Hilary Tovey, Karl Bruckmeier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Diversification and Innovation in Rural Development

Chapter 1

UK: Sustainable Livelihoods on the Island of Skye

Introduction

The island of Skye off the west coast of Scotland, UK, is used in this chapter as a case study to investigate the ‘performance’ of sustainable development by enterprises. The term sustainable development, in regular policy parlance, has come to convey development that takes social, economic and ecological (or environmental) sustainability into account. However, widespread acceptance by the EU member states ‘has led, not so much to change in policies and development strategies, but rather to an adoption of a common terminology that at best has some effects at the level of principles, strategies and policy programmes (where intentions are formulated), but much less at the level of implementation and actor strategies (where ideas are realized)’ (CORASON 2006, 82). What can we understand from starting from what local entrepreneurs actually do, rather than from high-level rhetoric about sustainable development?

This analysis does not aim to capture the totality of activity on Skye that might contribute to sustainable rural development. The performances that are investigated here are some that might traditionally fall under the rubric of ‘economic development’; the approach in this chapter is to look at how they deviate from modern economic thought which conceptualizes the economy as an autonomous ‘interlocking system of markets that automatically adjust supply and demand through the price mechanism’ (Block 2001), in which self-interested actors maximize individual profit. The aim is to raise the profile of this group of ‘alternative’ actors, and to discuss their approach as one that has a contribution to make to sustainable rural development.

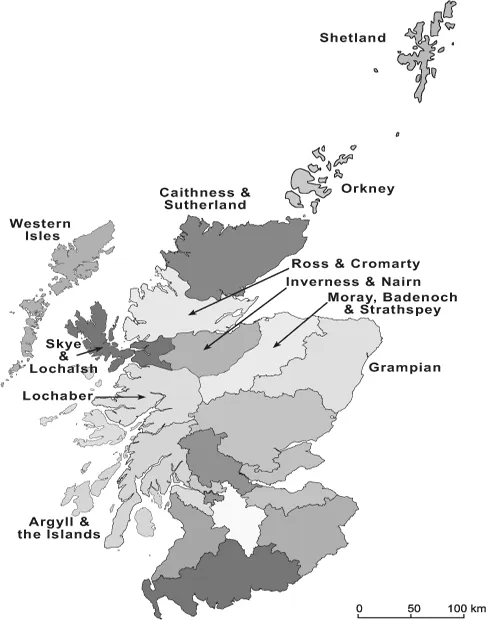

The Island of Skye, Scotland, UK

The island of Skye is the main land mass within the administrative area of Skye and Lochalsh, which is on the west of the Scottish Highlands and Islands, and one of the most remote parts of Europe (see Figure 1.1). It is located about 2 hours’ drive from the regional administrative centre of Inverness, 4 hours from the capital of Scotland, Edinburgh, and more than 15 hours’ drive and 1000 km away from London.

Figure 1.1 Skye and Lochalsh in the context of Scotland

Source: Nightingale, A. (2002).

The population of Skye and Lochalsh is 11,890 people, 76 per cent of whom live on the island of Skye. The average population density is 4/km2, but in fact a quarter of Skye’s population live in the island’s main centre, Portree. The area lost population from the nineteenth century until the 1970s, since when it has shown a slight growth – 3 per cent between 1991 and 2001 (Highlands & Islands Enterprise 2003) – due primarily to in-migration.

The economy was traditionally based around the primary industries, although the dominant tenure system (crofting) always meant a degree of diversification was necessary. Nowadays the tourism sector and the public sector provide 60 per cent of the island’s employment (Highlands & Islands Enterprise 1999). The 1997 Agriculture Census shows that about 14 per cent of the population of Skye and Lochalsh were still engaged to some extent in agricultural activity. Much of the employment is seasonal, low-skilled and insecure. Structurally, the economy is dominated by micro-businesses (<10 employees), with 25 per cent of employees working in firms with four or less staff (Highlands & Islands Enterprise 2003); there is a self-employment rate of over 20 per cent as well as comparatively high, and increasing, rates of business start-ups. However, business survival rates are relatively low.

Physically, the area is mountainous and inhospitable, but strikingly beautiful. Soils are thin and acidic, with very little cultivated land. Skye is better connected than most islands – a bridge was built connecting Skye with the mainland in 1997, and it also has more advanced telecommunications links with the outside world than many remote islands. However, it still suffers from a lack of local services.

A sketch of the island is not complete without mention of the ‘magic of Skye’. This is more than simply clever marketing jargon to attract tourists – it is something that permanent residents also recognize. The beauty of the landscape is central to this ‘magic’, through its ability to enchant with its changing moods and colours; for some the quiet lifestyle and the closeness of communities conjures up ‘imaginaries’ of rural idylls; the spirit of Skye is also tied up in its history – especially the draconian ‘clearances’ of the land in the nineteenth century – and in its traditional musical, artistic and language cultures.

Sustainable Livelihoods

The concept of sustainable livelihoods emanates from development studies, with the work of Chambers (and colleagues at the Institute of Development Studies) being seen as seminal (for example, Chambers 1988, Chambers 1997; Chambers and Conway 1991, Scoones 1998). Although the approach was intended to provide an understanding of livelihoods and how policy might impact on them (Korf and Oughton 2006), it was quickly taken up by governments and aid agencies such that a sustainable livelihoods approach has often been perceived to be about the interventions made by such organizations. In this chapter it is our intention to use the concept of a sustainable livelihoods approach in its original form, with the strategies of local people being the approach of interest, rather than the prescriptions of external organizations.

We are not alone in identifying the potential for taking this concept from development studies and applying it in a more developed context (for example, Korf and Oughton 2006), but still need to proceed with caution. It is not our intention to provide a systematic evaluation of activities on Skye against an agreed set of principles of the sustainable livelihoods approach – which, in any case, does not exist (Scoones 1998) – rather, we use it as a rhetorical device to explore how people ‘construct and contrive a living’ (Chambers and Conway 1991, 8), in ways, and for reasons, that may be far more diverse than those suggested by orthodox capitalist economics.

Ellis (2000), developing the definition provided by Chambers and Conway (1991) (and quoted extensively by other authors), suggests ‘A livelihood comprises the assets (natural, physical, human, financial and social capital), the activities, and the access to these (mediated by institutions and social relations) that together determine the living gained by the individual or household’ (p. 10). The five commonly cited assets are a ‘diverse repertoire of resources’ (Chambers 1988, 6) that are far more wide-ranging than the traditional factors of production (finance, land, and labour) of economic theory. However, many commentators argue that these assets are not necessarily all available to everyone equally (for example, Chambers and Conway 1991, Sen 1984) – Ellis’s reference to ‘access’. A person’s ability to access the assets, or to act in certain ways, may be limited (or enhanced) by who they are, by rules and customs, or by the interventions of the state and development agencies. The final point of Ellis’s definition emphasizes how combining available assets with the capacity to take action need not take place at the individual level (the focus of most economic analysis). In fact, Scoones (1998) goes well beyond Ellis’s individual or household level, identifying also the village, regional or national level as possible sites for livelihood strategies.

The use of the term ‘strategy’ implies active, goal-oriented behaviour (Small 2005). The origins of the sustainable livelihoods concept in development studies and its close association with poverty reduction programmes mean that there is a focus on survival strategies; it is common for strategies to be analysed in the context of external shocks and crises (Ellis 2000). Some commentators, though, see alternative rationales – adaptation strategies (Davies 1996); accumulation strategies, and changing to a better way of life (Dorward and Poole 2003).

Consensus is lacking on the specifics of the desired outcomes of a sustainable livelihoods approach, although it is clear that they are far more holistic than the common economic goals of increased production, employment and cash income (Chambers and Conway 1991, 3). For some, securing a sustainable livelihood is paramount (for example, Ellis 2000); others refer to the elusive concept of improved well-being: Scoones (1998) lists self-esteem, security, happiness, stress, vulnerability, power and exclusion as key measures (p. 6); Chambers and Conway (1991) talk of providing the ‘conditions and opportunities for widening choices, diminishing powerlessness, promoting self-respect, reinforcing cultural and moral values, and in other ways improving the quality of living and experiences’ (p. 8). Improved well-being is not only about objective measures of people’s well-being, but ‘the meaning that they give to the goals they achieve and the processes in which they engage. A key element of this last dimension of meaning, and a basic driver of the future strategies and aspirations of the person, is the quality of life that they perceive themselves achieving.’ (McGregor 2006, 4).

For the purposes of this chapter, the sustainable livelihoods approach focuses attention on how economic activity is not something that can be ‘disembedded from context’ (Ray 1999). It is not necessarily something performed out of the home, in ‘work time’, or clearly demarcated from ‘non-economic’ activity. It guides us to look for a portfolio of means of sustaining an income, rather than a single job, or business, and for collective approaches as well as individual strategies. And it emphasizes that both the resources engaged to produce a living, and the desired benefits can go well beyond the economic. The next sections of this chapter address aspects of the approach to development taken by some people on the island of Skye that resonate with ‘the holistic range of resources and activities, with and without direct monetary return, which are important to livelihood maintenance’ (Small 2005, 20). We then go on to discuss the appropriateness of the sustainable livelihoods approach to achieving sustainable rural development on Skye.

Income Generation Strategies

There is a long history on Skye of how the crofting culture made it necessary to develop portfolios of activities in order to secure a living. This system, imposed on tenants in the nineteenth century, deliberately created holdings too small to provide a full-time income, so as to ensure a supply of cheap, compliant labour for the landowners’ kelp industry. As this industry declined, crofters were left with unviable smallholdings, and therefore had to find alternative ways of supplementing their incomes. The 1950s was a period with the potential for significant changes, with the Taylor Commission of Inquiry, and the setting up of the Crofters Commission. Amalgamation of crofts into larger, more viable, holdings was high on these agendas, but was resisted by most crofters, and these tiny smallholdings still dominate the agricultural land. An average croft is about one-fifth of the size of an average full-time Less Favoured Area livestock farm in Scotland, has less than one-tenth of the output, and provides one-twentieth of the income (Kinloch and Dalton 1990); however, there is considerable diversity.

In 2005 there were 1,866 registered crofts on Skye and the small islands, making a significant contribution to local livelihoods, given that the statistics for Skye and Lochalsh in 2001 show 5,500 people in employment (Highlands & Islands Enterprise 2003). The average age of a tenant crofter is 50, and of an owner-occupier crofter, 69. Crofting often makes only a small contribution to household income; family members must also work off-farm.

Tourism provides a substantial income for the residents of Skye, with the Wholesale, Hotels and Restaurant sector employing more than a quarter of the workforce for Skye and Lochalsh (Highlands & Islands Enterprise 2003), but is an important cause of the highly seasonal trends in unemployment. Some people overcome the seasonal fluctuations in income by having a sequential portfolio of jobs; others might rely on other household members to sustain a reasonable income during the winter months.

White Wave, set up on Skye in 1990, is an outdoor pursuits company run by a husband and wife team. Alongside this, they have developed their portfolio of income-generating activities by setting up an independent record label to produce and distribute Gaelic songs. This is not only indicative of the portfolio aspect of the livelihoods approach, but also of holistic well-being as a desired outcome. Pursuing an interest is highly valued, perhaps more highly than maximizing the income from the main company – when providing catered residential accommodation for their clients proved demanding, the accommodation became self-catering. White Wave’s owners do not see expansion as a target, believing that the success of a business lies in consolidation and sustainability.

Aiming to earn an adequate income, rather than a high income, is common: sometimes this is simply realistic in that many firms operate at the margins of viability, but sometimes it is about making lifestyle choices as in the White Wave example, and in the descriptions of the many ‘hobby growers’ in the horticultural network who are new arrivals in Skye, looking for a rural idyll. This is not necessarily only for the elite: many people are choosing to value aspects of their well-being that are not associated with money and, having achieved viability, are far more interested in pursuing a wide range of other benefits for themselves, their families, or sometimes their neighbourhood – an aspect that is drawn out in the next section which discusses the importance of ‘place’ for these entrepreneurs.

The Importance of Place

Many enterprises on Skye are embedded within place. The reason for, and nature of, the attachment takes many forms. The experience can be positive or negative: for some it may be more about being tied to the place than about choosing to become attached to it. ‘To many a person brought up on a north of Scotland smallholding, the pull exerted by the croft seemed as much of a curse as a blessing. If I were not born there and the very dust of the place dear to me,’ said one crofter in a moment of exasperation with his fate, ‘I would quit tomorrow.’ (Hunter 1991, 34). (This crofter’s love/hate relationship was first captured in evidence to the Taylor Commission 1954, 31).

For crofters, the relationship to place takes a number of forms. There is a formal, long-term, connection to their crofts via their tenancy agreements, and to agricultural practices. The succession of tenancies from parent to child, and the effort of past generations in improving the fertility of the soil, ties extended families to the area, and the long family histories on Skye put pressure on future generations to remain in crofting. The communal aspects of crofting and its management, typically via the common grazings and the associated Grazing Committees embed crofters into their neighbourhoods. This activity finds crofters coming together to manage the land to maximize the group’s well-being. As the common grazings are often loss-making, non-economic aspects of communal crofting contribute to well-being, such as the long-term security afforded by having a croft.

For the couple running the outdoor pursuits company, White Wave, the relationship is different. The place is important to them for its natural resources, which they use to provide outdoor experiences for their clients. As well as physical activities which utilize the local rivers and footpaths, the White Wave experience also involves appreciation of the local flora and fauna. However, the relationship with Skye goes far deeper than what is provided for the business; for one of the owners, his commitment to staying on the island was expressed as ‘the place comes before the business’. The owners are also are concerned that, where possible, their business should contribute to local well-being and support for others’ livelihoods. As well as providing some local seasonal employment, work placement opportunities are made available for local school children and university students in the outdoor pursuits business. The opportunities for local (young) people offered by this firm are perceived by funders such as Skye and Lochalsh Enterprise as of far more importance than the limited employment it can offer: it demonstrates how a business attractive to young people can be sustained.

A very different small firm on Skye – Gael.net, an IT firm specializing in providing web-based content management systems, set up in 1995 by a man born and raised on the island – also sets out to make a contribution to local well-being. In contrast to the outdoor pursuits company described above, it can be judged a success in a classical economic sense: profit (from earned income) is healthy; it has had steady growth and has further expansion plans; and it now employs 17 staff. It contributes to the well-being of the neighbourhood in a number of ways. Each year, the company provides work experience for four to six students from the local school; some of these stay on with the company when they leave school and are given on-the-job training and certification. The company also funds awards at the local high school and sponsors the local football ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations and Glossary

- Introduction: Natural Resource Management for Rural Sustainable Development

- PART I DIVERSIFICATION AND INNOVATION IN RURAL DEVELOPMENT

- PART II ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABILITY IN RURAL DEVELOPMENT

- PART III COMPARISON AND SYNTHESIS OF CORASON CASE STUDIES

- Conclusion: Beyond the Policy Process: Conditions for Rural Sustainable Development in European Countries

- Index