eBook - ePub

Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making

About this book

Using the borderscapes concept, this book offers an approach to border studies that expresses the multilevel complexity of borders, from the geopolitical to social practice and cultural production at and across the border. Accordingly, it encourages a productive understanding of the processual, de-territorialized and dispersed nature of borders and their ensuring regimes in the era of globalization and transnational flows as well as showcasing border research as an interdisciplinary field with its own academic standing. Contemporary bordering processes and practices are examined through the borderscapes lens to uncover important connections between borders as a 'challenge' to national (and EU) policies and borders as potential elements of political innovation through conceptual (re-)framings of social, political, economic and cultural spaces. The authors offer a nuanced and critical re-reading and understanding of the border not as an entity to be taken for granted, but as a place of investigation and as a resource in terms of the construction of novel (geo)political imaginations, social and spatial imaginaries and cultural images. In so doing, they suggest that rethinking borders means deconstructing the interweaving between political practices of inclusion-exclusion and the images created to support and communicate them on the cultural level by Western territorialist modernity. The result is a book that proposes a wandering through a constellation of bordering policies, discourses, practices and images to open new possibilities for thinking, mapping, acting and living borders under contemporary globalization.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making by Chiara Brambilla,Jussi Laine,Gianluca Bocchi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Geopolitics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Conceptual Change in Thinking Borders

Chapter 1

Spaces, Lines, Borders: Imaginaries and Images

From ‘Salvation Lurks Around’ to ‘The Foreigner’

Born in a small Balkan city, he grows up in Africa, lives in India, settles down in Germany. The family is Orthodox; he converts to Islam. His mother tongue is Bulgarian, yet for the language of his art, he chooses German. A life worthy of a novel or a movie. What will be examined here, however, is not his (Ilija Trojanow’s) life as a novel or a movie, but his novel and movie The World is Big and Salvation Lurks Around the Corner.

In a car accident a young German loses his parents and his memory. A grandfather appears out of nowhere. Fallen into utter apathy, the young man wants to know nothing, wants to do nothing. The grandfather pushes him to move on. A long journey follows, on bikes, though the whole of Europe, from Germany to Bulgaria. Returning to the places of exile, diving into the painful temporality of an escape. A voyage through space, a voyage through time.

During the Communist period the father is a talented engineer, free-minded and rebellious, constantly challenging the party secretary. His unruliness is not forgiven and, in order to discipline him, it is decided that he should be made an informant for the secret services. An impossible choice: to yield and stop being himself or to find an elsewhere where remaining himself would be possible. He grabs his young son and leaves, his wife unwillingly joins this escape into the unknown. They cross the border in the night. A soldier sees them, yet pretends he does not – he is giving them a second life. A second life of vicissitudes in refugee camps, hardships, broken professional and personal life ensues. Finally, the young man recovers his memory and, most importantly, rediscovers and reinvents himself. Reconciled with his past, he liberates himself from the existential worry of the lost, of those who do not belong, to find confidence and balance, love, the capacity to choose for himself, to decide, to act. The World is Big and Salvation Lurks Around the Corner by Ilija Trojanow and Stephan Komandarev won several international awards and the hearts of Bulgarian spectators.

The Foreigner by Niki Iliev tells a different story: the instant a young Frenchman lands in Sofia he falls in love with a young Bulgarian, and to find her goes from one end of Bulgaria to the other, carrying with him with a ton of intercultural misunderstandings. He does not succeed and leaves. She then goes to try to find him through whole of Europe, again with a ton of intercultural baggage. Relatives of the two characters then become part of the comic mix of mirrored stereotypes, misunderstandings, in which the liking of the exotic foreign precedes mutual understanding. The genre being what it is, love stems from each frame, and the final frame can barely contain it. This romantic comedy of interculturality did not become an art phenomenon, but a sociological one – Bulgarian families went together with foreign friends, to laugh together, to enjoy the strangeness not as drama, but as fun, mobility not as an escape or trauma, but as searching and finding.

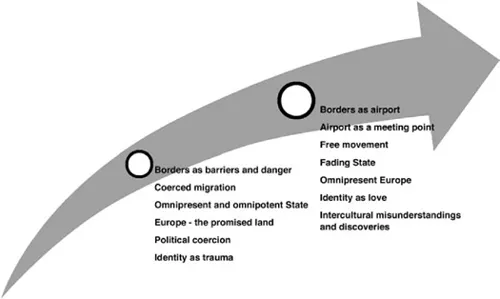

Those films tell two opposing tales of borders (Figure 1.1). In the first migration is the forced crossing of a forbidden border, an escape from a life-in-impossibility; in the second, migration is playfully replaced by light mobility and free movement. In the communist narrative the state, represented by the party secretary and the soldier, is personified not only in the Weberian terms of legitimate violence, but also as Foucauldi’s panopticon, of omnipresent surveillance and punishment. In the new tale the state has faded, it is present through the topos of the airport as a border, but a border that does not divide categorically and dramatically, but promises cultural surprises and new encounters. Europe is desired as the promised land, but happens as refugee camps in the communist story; in the new narrative it appears as unity in diversity – for the joy of European institutions, an almost literal and truly comical film translation of their normative image of charming and entirely complementary mix of cultures, identities, personalities: the femme fatale character speaks Bulgarian in a dialect, yet other European languages such as Italian are no hurdle. The political coercion and identity quests are intimately and traumatically entangled in the first case; in the second the existential quests are entirely autonomous from politics, which the comedy joyfully overlooks.

Figure 1.1 Two narratives of border

Source: Author.

Between the border as barbed wire and mortal danger and the border as an airport for meetings, between the metaphors of the salvation and love – the road from the traumatic communist migration experience of borders to European mobility is a long one. Those two tales mark the initial and the present point in the transformations of the borders, as well as of their imaginaries.

They also introduce two perspectives through which this chapter analyses borders – those of politics and poetry. We confront the political logic of the state and the micro-strategies of the actors with a highlight on the innovativeness of the latter in escaping the snare of the former; the political ‘heaviness’ of the narratives of surveillance and punishment and the individualised ‘lightness’, rich with symbolism of representations, images and imaginaries.

The two approaches refer to different images of the crossing of borders: arrows and spaghetti (Herzlich, 2004), the first refers to flows, the latter – to the individual paths. The arrow expresses the continuity and the typical; the spaghetti are the image of individualisation, unpredictability, change. The former refers to control, the latter – to individuation. The analysis is structured in three parts. The first follows the road of social sciences to space as a social construct, the fascination of space in contemporary art, and the spatial turn in social sciences. The second part examines the emergence of a new discipline – anthropology of lines, the gendered connotations of lines and the obsession of modernity with the straight line. The focus of the study is on the conceptualisations of borders as bordering, ordering, othering; the diversification of borders and the overproduction of symbols, images and imaginaries.

Spaces

Spatial Turn

The global has replaced the universal; space has replaced time (Therborn, 2000). As oppositional as globalisation and borders might appear be, they are both expressions of the same transition – from one established understanding of the social to a new one. The first has time as its cornerstone, the second – space. This epistemological change does not aim to turn its back on temporality or duration. Its ambitions are pointed in two other directions: relativising determinism, which is an inherent part of historicism, and, most of all, giving contingency a chance (Krasteva, 2004).

Space becomes a strong metaphor. The Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes describes the flamboyant characters of Columbian artist Fernando Bottero not in terms of beauty, but of space: ‘The women of Bottero are not fat. They are space. They are not insatiable for cakes and pastries. They are hungry for space’ (quote from Haralampiev, 2013). The spatial turn, which marked the social sciences in the 1990s, expresses the radical character of this theoretical transition and its ambition to offer an active understanding of space: Space is not only a passive reflection of social and cultural trends, but an active participant, i.e. geography is constitutive as well as representative (Warf and Arias, 2008, p. 8)

Space as social construction is the second theoretical insight. Being situated in space acquires more complex and deep meaning, the theoretical emphasis being put increasingly not only on multiple scales, but rather on multiple agencies: ‘[f]oundational is the insight that space is socially produced; rather than a mere physical container for the play of social forces and temporal relations, space is conceived at once as both the medium and presupposition for sociality and historicity’ (Houtum, Kramsch, Zierhofer, 2005, p. 4).

The road of the social sciences to arrive at space as a social construction has been already paved by philosophy. In ‘Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence’ Emanuel Levinas asks: Would proximity be a certain measure of the interval narrowing between two points or two sectors of space, toward a limit of contiguity and even coincidence? He gives two answers: ‘[…] the term proximity would have a relative meaning. Its absolute and proper meaning presupposes “humanity”’ (Levinas, 2009, p. 81). E. Levinas is representative of the passage, brilliantly elaborated by modern philosophy, from Euclidean conception of geometrical space and Descartes’s understanding of space as attribute of things to twentieth century phenomenology. As Heidegger claims, we cannot not ask what time/space is, we can only ask how time/space comes to us.1

Two pieces of contemporary art can illustrate this passage from the classic to the new understanding of space: the famous ‘Balzac’ of August Rodin and the ‘Post-Balzac’ of Judith Shea. Rodin’s sculpture made the illustrious writer appear larger than life, a creative genius rising above ordinary events. The contemporary reading of J. Shea depicts the writer’s robe without the man inside it. In the former case, we admire the plenitude, in the second the coat is empty, we see the contours of nothingness. The original expressivity of Rodin’s sculpture provokes us to admire or reject, the empty robe of Shea expects from us to continue the artist’s work, to fill in the coat, to invent the content. And because of the multitude of spectators’ looks, the contents will be legion.

Space more and more sheds its secondary role of a passive place in which a piece of art is to be positioned. It begins to play first violin. This new role is declared in the definition ‘work in situ’ – key to the art of Daniel Buren: ‘a piece of art is born in the space in which it is inscribed’. Works are exhibited in a museum, yet their creation unfolds in the parallel space of the atelier. The relations between the work and the museum can be tense, the messages of one and the other – conflicting. D. Buren reverses this relation: both the thought, and the realisation of the work of art are deduced and produced in the place of the exhibition, inspired by the place, inextricably linked to the place. This radical gesture confirms the primacy of the place: the piece of art exists only in the place and is destroyed, when it is to release it.

The primacy of the location, produced as creative rethinking of the place – art begins, more and more, with this challenge. The Museum of Modern Art in Paris gives all of the vast spaces of Palais de Tokyo to Philippe Parreno, who inhabits it with videoart, pianos, machine reproducing the author’s signature, object enchanting with lights, all poetically mixed under the title ‘Anywhere, Anywhere Out of the World’.2 ‘Architecture does not exist anymore before the exhibition, but the exhibition projects its own space’.3 The exhibited space does not accommodate ready works of art, but ‘creates’ them through the form that inspires, orientates, and stimulates.

‘Concepts of space’ consolidates the attention to the reconceptualisations of space. It could be the title of an academic work, but it is the title of a rich series of paintings, sculptures, compositions by Lucio Fontana, which he created in the long period between 1950 and 1965. The rethinking of space intrigues to an equal extent artists and scholars. The new vision is perceived as so revolutionising, it requires a fundamental document, which Lucio Fontana creates in 1951: ‘The Manifest of Spatial Art’. While debating the space shift in Begramo, we visit Bergamo’s Museum of Modern Art which welcomes us with the book ‘Negative Space’.

The classic understanding of space is clearly defined in terms of geography and politics, the constructivist one is open and demands a more complex understanding. Etienne Piguet reads space through social inequalities:

Space does not diminish in the same way for everyone. In the domain of migrations, all changes in accordance with who you are. For a university professor or an IT expert, barriers to outside Europe immigration would dissolve, allowing him, with his family, to settle down in Switzerland without delay. For an asylum seeker, those barriers will stay perhaps uncrossable. For a cabaret dancer coming from Eastern Europe, it would be possible to earn in Switzerland, but for eight months only, without any members of her family, not even a child, and without any hope of ever having the right to practice a job other than this very specific one for which her permit has been granted. (Piguet, 2004, p. 8)

The social construction of space invalidates some classical laws, i.e. the one of Ravenstein of end nineteenth century that the number of migrants diminishes with the distance (Piguet, 2004). The explanatory weight of distance is downgraded. Proximity/distance are not so much spatial variables in the interpretation of social processes, rather they could be but explained by social factors. The location and geographical distribution of social groups such as refugees becomes exclusively a function of governmental policies and strategies of individuals to resist them. The relevant concepts are not distance/proximity, but politically regulated closeness and socially defined inequalities: This geography is also of the one of world inequality (Piguet, 2004, p. 8).

Space shrinks like a peau de chagrin. Geographers such as Etienne Piguet illustrate this devolution in a series of images of the globe as in a modern art installation: a big one in 1840, considerably decreased in 1930 after the trains and massification of ships, shrinking even more from 30s to 60s after the first long distance flights, already very small in 80s with regular and cheaper flights. What’s the globe image in the spatial imaginary of twenty-first century? No materiality any more, just a question mark – ‘?’ – in Piguet’s scheme (ibid.). Social sciences know more of what space used to be than what it’s becoming.

Lines

The space shift produces a new cluster of interferential concepts. Key amongst them is the line. The production and meaning of lines have gained such theoretical weight that a new science has been created to take on the new research queries – the anthropological archaeology of lines. Tim Ingold is the pioneer of this new discipline, whose foundations he lays down in ‘Lines: A Brief history’ (Inglod, 2007). The Bergamo conference4 showed us the film Closed tracing refugee roads. It links to Tim Ingold’s conceptual distinction between traces and threads. The traces of refugees are fundamental for building memory for justice: from Ariana’s thread to the refugee networks and the global network world of M. Castells – all illustrating how key threads are.

The first paradox, that western reflection on lines faces is the large variety of lines and the domination of one line. Opposition in Chinese thought – Yin and Yang – are complementary, they form a circle; oppositions in Western thought are poles, two extremes of a line. Temporalities also follow different lines: the vision of the rise and fall of civilisations fits into the circle; the vision of development, progress, and change follows the straight line of the arrow. Nothing intrinsic in the line makes it straight. Why and how does the line become straight? Why is western modernity so obsessed with the straight line of the arrow, ponders Tim Ingold, and seeks in answer in three directions: the straight arrow is the image of space, which synthesises the three pillars of the western world view: progress; order, separation, classifications; linearity, rationality, civility, moral rectitude (Ingold, 2007, pp. 152–3). The civilisational preferences for one line or another are supplemented by gender specificities: the straight line is associated with masculinity, the curved line – with femininity. Furthermore, different types of societies refer to different lines: the traditional to topian, modernity to utopian, postmodernity to dystopian: ‘[t]he line of wayfaring, accomplished through the practices of dwelling and circuitous movements they entail, is topian; the straight line of modernity, driven by a grand narrative of progressive advance, is utopian; the fragmented line of postmodernity is dystopian’ (Ingold, 2007, p. 167).

Theoretical efforts strive to overcome the oppositions: Kenneth Olwig urges us to move beyond modernism’s utopianism and postmodernism’s dystopianism to a topianism of human beings, who as creatures of history, consciously and unconsciously create places (Ingold, 2007, p. 167). For my analysis of borders as lines, the distinction between the straight lin...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Dedication

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction Thinking, Mapping, Acting and Living Borders under Contemporary Globalisation

- Part I Conceptual Change in Thinking Borders

- Part II Everyday Processes of Bordering

- Part III Exploring Shifting Euro/Mediterranean Borderscapes

- Part IV Rebordering State Spaces City Borders and Border Cities

- Part V Cultural Production and the Emergence of New Borderscapes

- Index