- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Popular Music and the Myths of Madness

About this book

Studies of opera, film, television, and literature have demonstrated how constructions of madness may be referenced in order to stigmatise but also liberate protagonists in ways that reinforce or challenge contemporaneous notions of normality. But to date very little research has been conducted on how madness is represented in popular music. In an effort to redress this imbalance, Nicola Spelman identifies links between the anti-psychiatry movement and representations of madness in popular music of the 1960s and 1970s, analysing the various ways in which ideas critical of institutional psychiatry are embodied both verbally and musically in specific songs by David Bowie, Lou Reed, Pink Floyd, Alice Cooper, The Beatles, and Elton John. She concentrates on meanings that may be made at the point of reception as a consequence of ideas about madness that were circulating at the time. These ideas are then linked to contemporary conventions of musical expression in order to illustrate certain interpretative possibilities. Supporting evidence comes from popular musicological analysis - incorporating discourse analysis and social semiotics - and investigation of socio-historical context. The uniqueness of the period in question is demonstrated by means of a more generalised overview of songs drawn from a variety of styles and eras that engage with the topic of madness in diverse and often conflicting ways. The conclusions drawn reveal the extent to which anti-psychiatric ideas filtered through into popular culture, offering insights into popular music's ability to question general suppositions about madness alongside its potential to bring issues of men's madness into the public arena as an often neglected topic for discussion.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Popular Music and the Myths of Madness by Nicola Spelman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

‘All the Madmen’: Denouncing the Psychiatric Establishment and Supposedly ‘Sane’ Through the Art of Role Play

‘All the Madmen’ is the second track from The Man Who Sold the World,1 the album generally regarded as marking the beginning of David Bowie’s hard rock period.2 The song’s incorporation of role play, alongside its apparent veneration for the identified ‘mad’, make it a prime example of the way in which musical and verbal gestures can function to invoke an effective reversal of traditional concepts of madness and sanity.

Due to the quick succession of albums released, and Bowie’s previous interest in narrative forms, it is likely his audience throughout the early 1970s would have been accustomed to his use of characterization. As Allan Moore reveals: ‘Bowie forced attention upon the notion that a performer can inhabit a persona, rather than that persona being an aspect of the performer.’3 In the song ‘All the Madmen’ Bowie is playing the character of the labelled madman while still projecting the persona of the rock star. Our reading of Bowie’s character is thus shaped by our knowledge of his star status and vice versa; the distancing between them is what Frith refers to when he compares the act to that of a film star playing a role: ‘In one respect, then, a pop star is like a film star, taking on many parts but retaining an essential “personality” that is common to all of them and is the basis of their popular appeal.’4 While this observation regarding characterization may seem obvious, it has a greater relevance within this particular song for it enables a reading based on what has been termed the conspiratorial model of madness.

In The Myth of Mental Illness (1961), Szasz argues that what the majority of society and the psychiatric establishment refer to as mental illness is fundamentally separate and distinct from organic brain disease: ‘Strictly speaking, disease or illness can affect only the body; hence, there can be no mental illness. “Mental illness” is a metaphor. Minds can be “sick” only in the sense that jokes are “sick” or economies are “sick”.’5 In Szasz’s opinion, so-called ‘mental illness’ should therefore lose its mythical identity and be correctly defined as ‘personal, social, and ethical problems in living’.6 He offers a number of persuasive arguments in an attempt to elucidate the creation and perpetuation of this myth. The most crucial of these concerns the way in which mental illness serves as justification for the authority of the psychiatric profession while providing society with a means of labelling and hence scapegoating individuals whose behaviour is deemed undesirable:

Institutional Psychiatry is largely medical ceremony and magic. This explains why the labelling of persons – as mentally healthy or diseased – is so crucial a part of psychiatric practice. It constitutes the initial act of social validation and invalidation, pronounced by the high priest of modern, scientific religion, the psychiatrist; it justifies the expulsion of the sacrificial scapegoat, the mental patient, from the community.7

What is of particular relevance here is Szasz’s insistence that ‘mental illness is not something a person has, but is something he does or is’.8 In this sense once someone is, for whatever reason, labelled ‘mad’, they are, as a consequence, encouraged to take on the role of the insane person, as Szasz explains: ‘mental illness is an action not a legion. As Shakespeare showed […] it is also an act, in the sense of a theatrical impersonation.’9 Within my analysis of ‘All The Madmen’ one of my aims will therefore be to illustrate the ways in which Bowie’s characterization of madness represents Szasz’s myth of mental illness, for it exposes the myth for what it is – a role, a form of game play and a performance.

The theme emphasized initially in the song is that of alienation, or more specifically the alienation inherent within society itself. In the introduction and first two verses the listener is encouraged to feel empathy for Bowie’s character, who is left behind while his friends are taken away to ‘mansions cold and grey’. The imagery here draws upon eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century depictions of madhouses that were criticized for their inhumane methods of treatment and wrongful confinement. In her unfinished book The Wrongs Of Woman (1797) Mary Wollstonecraft’s protagonist, Maria, is incarcerated in a ‘mansion of despair’;10 Henry Mackenzie describes the living quarters of Bedlam in his classic The Man of Feeling (1771) in terms of ‘dismal mansions’;11 and John Conolly, a Victorian physician and head of Hanwell Asylum in Middlesex, told of the dreadful conditions prior to the licensing and inspection of asylums, referring to ‘gloomy mansions in which hands and feet were daily bound with straps or chains’.12 While the act of incarcerating people presumably against their will is called into question here, it is not, however, the source of Bowie’s character’s sadness. Rather, it is the isolation of the world in which he remains that proves undesirable.

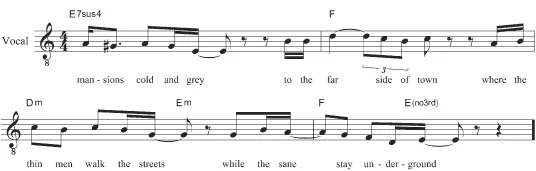

The sparse accompanying texture, comprising plectrum-strummed, steel-strung acoustic guitar and a lone synth call (which fades in and out a minor 6th above the tonic E), provides a suggestively bleak backdrop that is heightened by stark 4th and 5th intervals between two recorder sounds in verse two. The use of strummed acoustic guitar creates a sense of intimacy, being associated as it is with an accompanying role in songs with a more personal message, and this contrasts with the distancing of the vocal itself achieved through the use of panning and artificial reverb. The reverb seems excessive and effectively evokes the isolation of Bowie’s character, while the spatial dimension is significant in that the guitar shifts from far left to far right to make way for the voice entering alone, far left. This effect is further enhanced through the melodic line which, despite its use of an ascending major scale, appears confined and non-directed during the first two bars. Rhythmically dislocated, there are few obvious points of phrase repetition and the rhythms are sometimes clipped, sometimes lengthened to accentuate particular aspects of the lyric content (for example, ‘send’, ‘friend’, ‘mansions’ and ‘far’). The unhappy separation of Bowie’s character from his ‘friends’ is also emphasized through a leap up to the minor 7th and a 6–5 appoggiatura which stresses the word ‘far’ before descending back to its starting point via E Phrygian. The contour of the melodic line during the verse thus resembles a sigh; it grows in pitch and complexity, incorporating more non-harmony notes, before finally resolving back to the tonic (see Example 1.1).

The fact that the harmony resists change during the first three bars of the verse also offers little comfort, for the major identity is repeatedly challenged by the shift to E7sus4 in the beginning of bars two and three. The eventual move up a semitone to the F chord in bar four does offer some sense of release, but the progression to E Phrygian denies any reassurance of diatonic closure. The choice of Phrygian mode is in itself significant, having traditionally been used in western musical idioms to symbolize the unfamiliar with its characteristic minor 2nd interval carrying, according to Robert Walser, a ‘frAntic, claustrophobic effect’.13 While the tonic E remains a recognized point of stability during the verse, the harmonic language and modal melodic inflections are uncertain and this in turn represents the feelings of unease that surround Bowie’s character.

Example 1.1 ‘All the Madmen’ verse 1 (vocal and chords)

The sense of isolation and restlessness evoked in the opening musical and lyrical gestures is, I would argue, crucial to the overall message of the song. If Bowie’s protagonist is to convince us of his desire to stay with ‘all the madmen’, then we must have a point of comparison – his feelings in the opening represent the alternative, a life of loneliness among the supposed ‘sane’. While not an original concept, it does appear to reflect the thinking of R.D. Laing and his theory of man’s estranged state which he first articulated in The Politics of Experience (1967). Laing wrote: ‘The condition of alienation, of being asleep, of being unconscious, of being out of one’s mind, is the condition of the normal man’14 and he supported his belief by claiming that, for many people, their ‘true self’ is lost behind a ‘false self’ acquired to deal with a society that is profoundly estranged from reality.15 Such views had, in fact, become commonplace in the New Left’s attempts to highlight the necessity for social change, a change that would require involvement on a personal level to overcome what Theodore Roszak referred to as ‘the deadening of man’s sensitivity to man’.16 The suggestion that humanity’s ‘true self’ had been lost behind a mask adopted to succeed within a fake social reality was equally appealing to those who had chosen to ‘drop out’ of society – the Bohemian fringe of the counter-culture. Unsurprisingly, Laing became associated with the aforementioned groups and, indeed, similarities in his use of language are revealed if one compares arguments posed within The Politics of Experience with an extract from the SDS Port Huron Statement of 1962:17 ‘we regard man as infinitely precious and possessed of unfulfilled capacities for reason, freedom and love […] Loneliness, estrangement, isolation describe the vast distance between man and man today.’18 One can, of course, only postulate that such thinking had an impact on Bowie, although biographical writers such as Kate Lynch have pointed to his creation of a Bohemian lifestyle during his time at Haddon Hall (the setting for the original and controversial cover to The Man Who Sold the World)19 and his interest in Tibetan Buddhism (‘One must question one’s existence and when you do it leaves you with an incredible loneliness … Buddhism made me very keen on creativity’).20 Accompanied by statements in which he criticized ‘the whole idea of Western life’,21 these suggest a certain identification with contemporary radical opinion.

The notion that labelled madmen were, in fact, enlightened, honest, artistic individuals wrongly scapegoated by a sick society seems to have become more common during the late 1960s and early 1970s when through literature, film and music a number of artists set out to challenge conventional notions of ‘mad’ behaviour. In a similar affront to the Establishment, labels of insanity were used by certain theorists to criticize a society that continued to sanction acts of greed and war; and Michael Fleming’s research into portrayals of madness is valuable here, for he claims: ‘The production of such films [by which he is...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- General Editor’s Preface

- List of Music Examples

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 ‘All the Madmen’: Denouncing the Psychiatric Establishment and Supposedly ‘Sane’ Through the Art of Role Play

- 2 ‘Kill Your Sons’: Lou Reed’s Verification of Psychiatry’s Covert Social Function

- 3 Reversing Us and Them: Anti-Psychiatry and Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon

- 4 ‘The Ballad of Dwight Fry’: Madness as Social Deviancy, and the Condemnation of Involuntary Confinement

- 5 The Fool’s Demise: Critiques of Social Exclusion Found in the Beatles’ ‘The Fool on the Hill’ and Elton John’s ‘Madman Across the Water’

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Discography

- Index