- 274 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Wellbeing and Place

About this book

The last twenty years have witnessed an important movement in the aspirations of public policy beyond meeting merely material goals towards a range of outcomes captured through the use of the term 'wellbeing'. Nonetheless, the concept of wellbeing is itself ill-defined, a term used in multiple different contexts with different meanings and policy implications. Bringing together a range of perspectives, this volume examines the intersections of wellbeing and place, including immediate applied policy concerns as well as more critical academic engagements. . Conceptualisations of place, context and settings have come under critical examination, and more nuanced and varied understandings are drawn out from both academic and policy-related research. Whilst quantitative and some policy approaches treat place as a static backdrop or context, others explore the interrelationships of emotional, social, cultural and experiential meanings that are both shape place and are shaped in place. Similarly, wellbeing may be understood as a relatively stable and measurable entity or as a more situation-dependent and relational effect. The book is structured into two sections: essays that explore the dynamics that determine wellbeing in relation to place and essays that explore contested understandings of wellbeing both empirically and theoretically.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Wellbeing and Place

Serious moves are afoot to shift the assumptions of governments and populations alike away from the idea that a flourishing life is primarily connected to material prosperity and towards positioning wellbeing as the ultimate goal for policy intervention (NEF 2004, Stiglitz et al. 2009). At the same time, there has been an ideological and rhetorical urge towards more responsive policy-making through greater local voice, local accountability and decentralized governance, a shift mobilized through an emphasis on the processes of place-making and place-shaping (Shneekloth and Shibley 1994, Steuer and Marks 2008, Wight this volume). These current shifts to reconfigure policy landscapes are predominantly in high income countries but intersect with existing debate over the aims of development interventions (Gough and McGregor 2007) and the impacts of both global and local inequalities (Singh-Manoux et al. 2005, Wilkinson and Marmott 2003, Wilkinson and Pickett 2009).

The centrality of two concepts, wellbeing and place, within contemporary governance and policy makes it timely to examine their possible meanings and the relationships between them through a range of academic inquiries that can offer policy relevance and critical reflection. This volume offers a collection of chapters from a range of disciplinary and policy-engaged directions arranged under two broad categories: those determining wellbeing’s relationship to place and those contesting the definitions and relationships of wellbeing and place. In framing an introduction to the collection, we argue that there is a dominant approach in wellbeing research and policy. This approach is reflected in research on wellbeing and place which can contribute in a relatively straightforward manner to current policy agendas and debate. This does not imply that such research cannot deliver trenchant critique or expose injustices in policy formulations and implementation (see for example, Jack this volume); on the contrary, research that can connect to dominant framings is more likely to have an impact on policy and see such critiques of formulation and implementation reflected in practice (see for example Beck this volume). However, there is a second body of research which interrogates the assumptions within a dominant approach. There is a wide range of theoretical and methodological perspectives from which this more conceptual critique may derive. Empirically informed research on differently situated understandings and experiences of wellbeing expose situated conflict and the power inequalities in terms of which perspectives are valued (see for example, Gibson this volume). Social theories provide critical analytical insights through which to interrogate further these highly situated relations of power (see for example, Little this volume).

The central argument in the emergence of wellbeing as a governing policy concept is that economic growth and material wealth should be seen as the means to a good life rather than the end itself. This argument has emerged through movements related to various political concerns including those addressing broad development goals (Anand and Sen 1994, Nussbaum 2000), environmentally sustainable living (Defra 2005, NEF 2004) and a focus on an individualized, psychological state of happiness or flourishing (Layard 2005, Seligman 2011). Whilst these different routes to a common call for policy to look beyond economic measures of social progress are all captured under a label of wellbeing, the various political engagements with the notion of wellbeing involve very diverse conceptualizations in terms of scale, scope, location and responsibility (Atkinson and Joyce 2011, Ereaut and Whiting 2008, Sointu 2005). A similar diversity of conceptualizations and methodology is reflected in the engagement with wellbeing across different academic disciplines (de Chavez et al. 2005).

An intellectual inquiry into what it is that makes for a good or flourishing life is nothing new. Scholars of wellbeing in Western Europe typically trace the contemplation of individual wellbeing back to classical Greece and to the competing philosophies of hedonic, or happiness and pleasure-based, wellbeing of Aristippus (Kahnemann et al. 1999) and eudaimonic, or satisfaction and meaning-based, wellbeing of Aristotle (Deci and Ryan 2008). The hedonic pathway can be tracked through later philosophical contributions of Mill and Bentham on how to select between alternative individual and collective actions in order to maximize the greatest happiness or utility for all. In recent times, psychologists working within the hedonic tradition have provided high profile and policy-relevant research including the contributions to a social policy of Ed Diener (2009) and the more personalized approaches to happiness and wellbeing of Martin Seligman (2002, 2011, see Table 1.1). The engagement of the economist, Richard Layard, with the concept of happiness and its determinants has been highly influential through providing renewed economic credibility to the concept (Layard 2005). Research showing that positive and negative affect constitute independent dimensions adds further intellectual complexity to understanding how an overall balance between these may be reached (Huppert and Whittington 2003). The eudaimonic pathway can similarly be tracked to its contemporary expression in both psychological and more economic fields. In psychology, this approach attends to the dynamic processes that enable and re-enable a sense of self-fulfillment, meaning and purpose (Deci and Ryan 2008); an influential approach of this kind is the six characteristics of psychological wellbeing defined by Ryff (1989; Ryff et al. 2004, see Table 1.2). The critical engagement with the policy intentions of development interventions, issues of social justice and inequity associated with the capabilities approach (Nussbaum 2000, Stiglitz et al. 2009, see Table 1.3) and the Wellbeing in Development (WeD) group (Gough and McGregor 2007) and the Wellbeing and Poverty Pathways collaboration (2011) offer broader engagements with wellbeing which combine objective and subjective assessment and cover material, relational, cognitive, affective and creative dimensions to wellbeing. However, whilst these different approaches offer a richness of perspectives and encounters with what might constitute a flourishing life, they are all challenged by the contemporary concern with environmental sustainability to incorporate a greater temporal dimension which can consider not just the sustainability of wellbeing within an individual life-span, but equally, if not more importantly, beyond and into future lives, of both human and other co-present species (Defra 2005, NEF 2005).

Wellbeing, however defined, can have no form, expression or enhancement without consideration of place. The processes of well- being or becoming, whether of enjoying a balance of positive over negative affects, of fulfilling potential and expressing autonomy or of mobilizing a range of material, social and psychological resources, are essentially and necessarily emergent in place. And, as with wellbeing, engagements with a concept of place have provided a rich field of debate and contestation. Whilst some quantitative and policy-relevant approaches treat place as little more than a static backdrop or a container against or within which social interactions occur, others, particularly from the field of human geography, have problematized this apparently common-sense approach to position place as inherently relational in both its production and its influence (Cresswell 2004). Contemporary policy for local governance reflects these more complex mobilizations of a relational place, as demonstrated through the importance increasingly given to processes that help to build a sense of community, social cohesion and trust, enhanced liveability and so forth, an approach which in some countries has come to be labelled as place-making or place-shaping (Mullins and Van Bortel 2010, Gallent and Shaw 2007, Wight, this volume). In these policy formulations, whilst place-making is an important outcome of local government, in relation to wellbeing it is clearly positioned only as a determinant of personal wellbeing, aggregated for the constituent population, rather than as an expression of a more collective or temporal wellbeing in its own right.

Policy-facing research on wellbeing tends to be embedded within an accepted line of argument that calls for greater clarity in definition and use of the term wellbeing. The argument is that first, we lack agreed terminology, definitions and monitoring tools, secondly that this is important because different understandings and definitions of wellbeing risk creating barriers to communication across different sectors involved in policy-making and thirdly, that in order to evaluate the benefits of different policy interventions in terms of enhancing wellbeing, standardized indicators and monitoring tools are essential (Ereaut and Whiting 2008). The co-existence of several discourses of wellbeing is evident within current policy debates (Atkinson and Joyce 2011, Ereaut and Whiting 2008) and the specifics of how wellbeing is defined in terms of the dimensions used and how these may be weighted in different approaches show great variation. However, despite such variation, there is nonetheless a considerable degree of convergence in the underlying approach taken in defining both wellbeing and place across policy documents and policy-facing research which can be seen as an emerging dominant approach in operationalizing wellbeing and place.

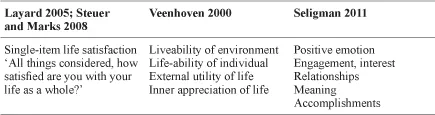

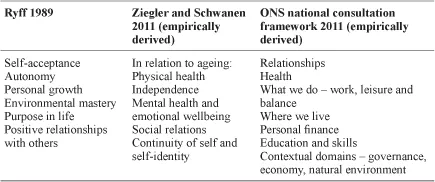

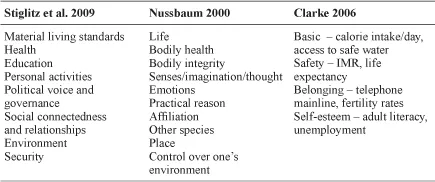

First, research mostly takes an approach to definition that deals with the abstract nature of the concept by breaking it down into constitutive dimensions in what we are calling a components approach to wellbeing. A components approach underpins economic and psychologically informed schemes of wellbeing and both hedonic and eudaimonic variants. Tables 1.1-1.3provide examples of some of the well-known frameworks for wellbeing that illustrate the components approach. Component lists have also been derived from empirical research on people’s own definitions of what is important to their wellbeing and one of many possible examples is the framework produced by the Office for National Statistics in the United Kingdom to shape a national consultation on wellbeing which was structured through a set of domains derived from preliminary public engagement (ONS 2011).

Table 1.1 Examples of Psychological, Subjective and Hedonic Components

Table 1.2 Examples of Psychological, Subjective and Eudaimonic Components

Table 1.3 Examples of Economic and Developmental, Objective and Subjective and Eudaimonic Components

A second feature of the dominant approach to wellbeing is that all these endeavours share a common understanding of wellbeing as a quality that inheres to the individual. The scope of wellbeing may range from an inner balance between positive and negative affect through to a breadth of components and it may be influenced by factors and processes from proximal personal interactions through to global scale processes. Wellbeing may be assessed objectively or subjectively, as a snap-shot of a current state, longitudinally across time or as a projection into the future, but in all these diverse scenarios, the central concept of wellbeing is itself individual in scale. Wellbeing was not always conceived of as an individual quality; earlier outings of the concept addressed collective aspects of the good life in terms of the economic wellbeing of the nation (Sointu 2005) or the moral landscapes that may inform or confront social and environmental injustice (Smith 2000). These aspects are now largely positioned as contextual influences on individualized wellbeing. Community or population measures of wellbeing exist in contemporary usage as aggregates of individual measures. Nonetheless, despite the individualization of wellbeing, there are still alternative, less dominant discourses of wellbeing in current policy communities that treat the concept as collective, most prominently in relation to sustainability and environment (Atkinson and Joyce 2011, see Wheeler this volume). Indeed it is the parallel existence of different mobilizations in different policy sectors that has given rise to calls to decide on an agreed terminology (Ereaut and Whiting 2008). The third feature of a dominant approach to wellbeing is that, despite variation in component sets as indicated in Tables 1.1-1.3, there has been a marked tendency for wellbeing to be used as a synonym for health, both in research and in policy (Atkinson and Joyce 2011; Ereaut and Whiting 2008; WHO 1948; see also Riva and Curtis this volume). Moreover, this conflation goes even further in that not only is wellbeing reduced to health, but particularly to mental health, to the absence of mental ill-health and increasingly to the concept of personal resilience (Atkinson 2011).

Debate in establishing sets of such individually attributed components centres on identifying which components are essential in defining wellbeing and which comprise the influences that produce wellbeing. Defining the essential set for wellbeing requires the specification of components that operate largely independently from one another and decision as to whether such components are best captured through objective or subjective assessments. The next step from these more conceptual elaborations of the nature and components of wellbeing is to identify associated, presumed influential, variables usually through quantitative research designs. In this there is a veritable burgeoning industry in exploring the determinants of wellbeing, from individual factors through to the global. Certain aspects of human life commonly feature in such explorations, including social relationships, health, safety and financial security, some variant of control in life, some variant of meaningful purpose, but, depending on how wellbeing is conceived initially, these may be cast as either dimensions to wellbeing or determinants of wellbeing. Thus in a hedonic psychological approach to a personal subjective wellbeing, economic and various other social elements are cast as determinants; this is the case in the Easterlin paradox, the much cited and influential proposition that happiness has not improved over time despite evident gains in material prosperity (Easterlin 1974; 1995, Layard 2005; see also Albor 2009 and Stevenson and Wolfers 2008 for a critique of this argument). By contrast, a eudaimonic, economic or developmental approach attempts to define the entirety of human flourishing through independent dimensions to wellbeing which cover a wide range of both objective and subjective components (Nussbaum 2000, Stiglitz et al. 2009).

There has been a vast quantity of research based on this kind of approach to wellbeing. In this, the fields of human geography and planning have contributed by their specific engagement with spatial relations. For example, Brereton et al. (2008) demonstrate how the inclusion of spatial variables into models exploring variation in subjective, hedonic wellbeing in relation to environmental characteristics can increase the explanatory power by a factor of three. Nonetheless, this engagement has, to date, predominantly focused on wellbeing as health, particularly within human geography (Collins and Kearns 2005, Cummins and Fagg 2011, Eyles and Williams 2008; Groenewegen et al. 2006, Kearns and Reid-Henry 2009, see also Conradson this volume for a review of the literature). New policy trends in governance towards place-making and the greater prominence of concerns with wellbeing are likely to generate indicators of wellbeing that can be disaggregated to units of local government and most likely to neighbourhood scales (NEF 2010). However, similar to the academic work within human geography, much of the existing planning and policy-facing research on wellbeing that has fore-grounded the specific influences of place and place-related variables has predominantly invoked a health-related interpretation.

The importance of subjective engagement with local environments has emerged strongly in research and planning in contrast to the existing convention of describing and assessing environment through objective measures. Michael Pacione (2003) has stressed this in respect to urban planning, while qualitative, empirical research with local residents has brought to light the importance of individual biographies in mediating and managing negative aspects of local environments (Airey 2003). The significance for wellbeing of subjective, emotional investments in objective, material markers of economic wellbeing is well illustrated in a study of investment in housing. Those who have made an explicit financial investment into their housing tend to score lower on a subjective wellbeing scale than more generalized investors. The latter group, being relatively relaxed about the return on their housing investment, take greater enjoyment from the affective and practical value of their housing (Searle et al. 2009). Whilst much of the research structured through the dominant approach to wellbeing treats place as something of a given, a static snapshot of settings in which various resources and experiences influence both objective and subjective wellbeing, the attention to subjective wellbeing inevitably draws in questions of what places mean to people and the role of emotional attachments to places (see Jack this volume). Such recognition is difficult to combine with a mobilization of place as contextual backdrop but rather insists on a reconceptualization of places as profoundly relational. Human geographers, for example, have described the mutual constitution of emotion and place as an emotio-spatial hermeneutic in which, ‘emotions are understandable – ‘sensible’ – only in the context of particular places. Likewise, place must be felt to make sense’ (Davidson and Milligan 2004: 524). The complexities and multiple interconnections in engendering personal and collective expressions of a situated and relational wellbeing, whether subjectively or objectively defined, ar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Foreword

- 1 Wellbeing and Place

- 2 Wellbeing: Reflections on Geographical Engagements

- 3 Understanding the Impact of Urban Green Space on Health and Wellbeing

- 4 The Significance of Material and Social Contexts for Health and Wellbeing in Rural England

- 5 Wellbeing and the Neighbourhood: Promoting Choice and Independence for all Ages

- 6 The Role of Place Attachments in Wellbeing

- 7 Am I an Eco-Warrior Now? Place, Wellbeing and the Pedagogies of Connection

- 8 Is ‘Modern Culture’ Bad for Our Wellbeing? Views from ‘Elite’ and ‘Excluded’ Scotland

- 9 Exploring Embodied and Emotional Experiences within the Landscapes of Environmental Volunteering

- 10 Place Matters: Aspirations and Experiences of Wellbeing in Northeast Thailand

- 11 Wellbeing in El Alto, Bolivia

- 12 A 21st Century Sustainable Community: Discourses of Local Wellbeing

- 13 ‘We are the River’: Place, Wellbeing and Aboriginal Identity

- 14 The New Therapeutic Spaces of the Spa

- 15 Place, Place-making and Planning: An Integral Perspective with Wellbeing in (Body) Mind (and Spirit)

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Wellbeing and Place by Sara Fuller, Sarah Atkinson,Sara Fuller,Joe Painter, Sarah Atkinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.