eBook - ePub

Governing Post-Imperial Siberia and Mongolia, 1911–1924

Buddhism, Socialism and Nationalism in State and Autonomy Building

- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Governing Post-Imperial Siberia and Mongolia, 1911–1924

Buddhism, Socialism and Nationalism in State and Autonomy Building

About this book

The governance arrangements put in place for Siberia and Mongolia after the collapse of the Qing and Russian Empires were highly unusual, experimental and extremely interesting. The Buryat-Mongol Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic established within the Soviet Union in 1923 and the independent Mongolian People's Republic established a year later were supposed to represent a new model of transnational, post-national governance, incorporating religious and ethno-national independence, under the leadership of the coming global political party, the Communist International. The model, designed to be suitable for a socialist, decolonised Asia, and for a highly diverse population in a strategic border region, was intended to be globally applicable. This book, based on extensive original research, charts the development of these unusual governance arrangements, discusses how the ideologies of nationalism, socialism and Buddhism were borrowed from, and highlights the relevance of the subject for the present day world, where multiculturality, interconnectedness and interdependency become ever more complicated.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Governing Post-Imperial Siberia and Mongolia, 1911–1924 by Ivan Sablin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Demographics, economy, and communication in the borderland, 1911–1917

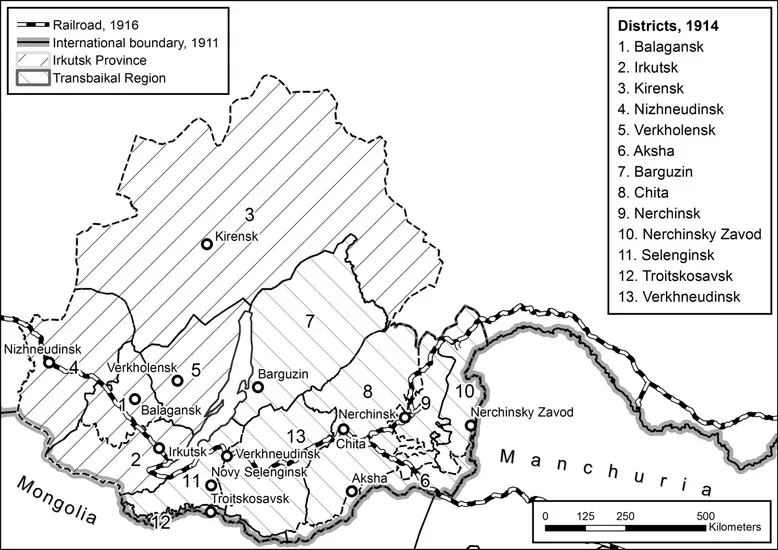

1.1 Russian and Qing governance structures

The representatives of the Qing and Romanov dynasties arrived at the future border region in the seventeenth century. The incorporation of the Baikal region into the Russian state began when the “men of service” (služilye lûdi), regular soldiers, and tradesmen (promyšlenniki) advancing eastwards of the Urals reached the lake, overcame the opposition of the local population, and established tributary relations with most regional groups (Forsyth 1992, 28–47). The rule of the Qing had spread to Inner Mongolia in the 1630s, before they established themselves as a new dynasty in China. The Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689 set the boundary between the two states along the Argun’. Two years later Outer Mongolia was incorporated into the Qing Empire (Cosmo 1998, 291–292). The Treaty of Kyakhta (1727) specified the Russian-Qing boundary. According to the Treaty of Aigun (1858) and the Convention of Peking (1860), the areas north of the Amur and on the Pacific coast became part of the Russian Empire (Bassin 2006; Habarov 2008, 1:21, 30–37) and the international boundary took the form which can be seen on the map (Figure 1.1) (Pereselenčeskoe upravlenie 1914b; 1914c; 1914g; W. & A. K. Johnston 1912).

For the regional population engaged in nomadic herding the boundary turned out to be a disaster, as it disturbed their seasonal migrations. The people had to decide which pastures to choose and on which side to pay tributes. All this resulted in major transboundary migrations before 1727 when the border was closed and minor resettlements throughout the rest of the eighteenth century (Bogdanov 1926, 52, 63, 74–75; Haptaev 1954, 1:101).

The Qing ruled Outer Mongolia, which was understood as the four Khalkha aymaks1 or the four aymaks plus Khovd and Tannu Uryankhai, through the regional nomadic elite. In the early twentieth century the four aymaks of Khalkha Mongolia consisted of khoshuns.2 Somons3 were the smallest administrative units from which the nobles with their dependents and the Buddhist clergy were exempt. The Qing authority was exercised by a military governor in Uliastai and two civil governors (amban) in Khovd and Urga. The highest religious authority in Mongolia since 1639 was the Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, a prominent lama in the Gelug tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. Inner Mongolia, which consisted of khoshuns united into six leagues, was administered by the Qing more closely. Apart from more self-government rights, Outer Mongolia was subject to more restrictive immigration policies for Chinese settlers as compared to Inner Mongolia (Cosmo 1998, 297, 300–302).

Figure 1.1 The political and administrative spaces of the Baikal region.

The administrative structures of the Russian Empire were marked by variety. In the early twentieth century the two Baikal provinces, the Irkutsk Province with the center in Irkutsk and the Transbaikal Region4 with the center in Chita, consisted of thirteen districts (Figure 1.1). Two Orthodox Christian eparchies corresponded to the provinces and shared their names. The two provinces also gave names to respective state chambers and settler districts. The larger Irkutsk Military Region, the Irkutsk Judicial Circuit, the Irkutsk Educational Circuit, the Irkutsk Supervisory Chamber, and the Irkutsk District Administration of Agriculture and State Property united the entire Baikal region with other areas in Siberia (Glinka 1914, fig. 10–17). These numerous administrative structures occasionally conflicted with each other (Damešek et al. 2007, 103).

Between the 1820s and early 1900s, the complex structures of imperial administration featured bodies of indigenous administrative, economic, and judicial self-government based on clan and territorial groupings: Clan Administrations, Alien Administrations, and Steppe Dumas (councils) (Vysočajše Utverždennyj 1830). The abolition of self-government in 1896–1901 resulted in major protests (Žalsanova 2008). The introduction of uniform Russian administrative divisions in the Baikal region can be seen as an attempt to turn the heterogeneous empire into a homogenous nation legally. This reform, which apart from the new divisions imposed land regulations unfavorable for the non-Russian population of the region, triggered the emergence of an organized Buryat national movement which manifested itself during the First Russian Revolution (1905–1907). Gombožab Cybikov, Tsyben Žamcarano, and other intellectuals campaigned for self-government, and education in the native language at Buryat congresses and in the press (Bazarov 2011, 15–16; Bazarov and Žabaeva 2008, 48–50).

The Buryat national movement responded to the grievances caused by the imperial policies. In 1901, indigenous peoples and Jews were the only two groups not allowed to acquire public land in Siberia. The land-use regulations passed in 1896–1901 and 1905–1917 put indigenous peoples in a marginalized position: their lands were seized to form the land fund for settler colonization and resolution of land shortage in European Russia; the lands which were ascribed to the indigenous peoples were not their property and the people had to pay land tax for it. Indigenous peoples were subject to social inequality, racial discrimination, and Russification policies which aimed at a full merger of Russians and non-Russians. Driven by racism, some high officials described the Transbaikal Buryats as potential allies of the “yellow race” in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) and discussed the idea of their mass resettlement to the inner provinces of the empire (Damešek et al. 2007, 58, 67, 213–214, 221, 236, 238–239).

The political space of the Russian Empire extended beyond the international boundary. With the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) in 1897–1903 Russian presence significantly increased in Manchuria. The CER Zone with the center in Harbin became Russia’s de facto colony. After its defeat in the war with Japan, which contested Russian presence in East Asia (Schimmelpenninck van der Oye 2001), the Russian Empire lost control over most of the South Manchuria Railway (Urbansky 2008). By 1911 semi-official Russian presence was also significant in Tannu Uryankhai. A 1911 Russian map of northern China used the colors of the Russian and Japanese empires to depict their zones of influence along the railroads and in Tannu Uryankhai (Kartografičeskoe zavedenie A. Il’ina 1911).

1.2 Waterways, railroad, telegraph, and other communications

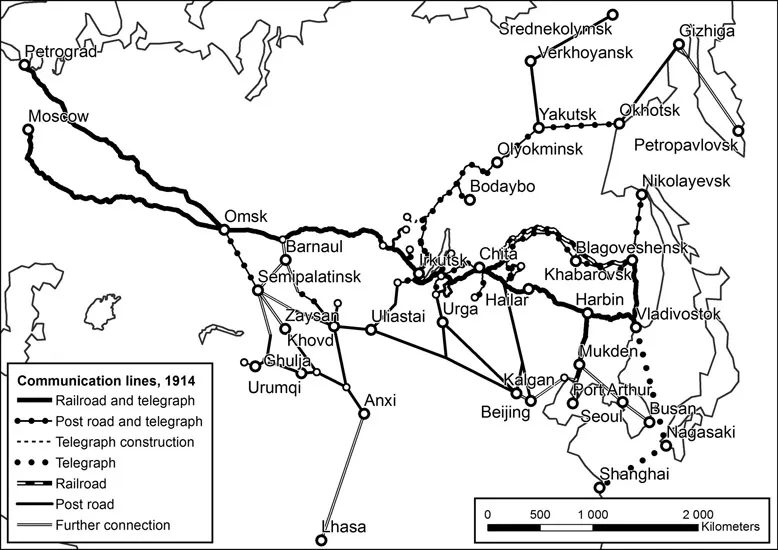

The Baikal region of the early twentieth century was often referred to as a periphery of the Russian Empire (Bazarov and Žabaeva 2008, 48; GARF 1701–1–16, 21; Gerasimova 1964, 3; Haptaev 1964, 23; RGASPI 372–1–210, 27 rev.). Indeed, the distance between the region and European centers in the geographical space was tremendous. In communication spaces and power structures of the Russian Empire, however, it played a very important role. The Lena, Angara, Ilim, Selenga, and Shilka all belonged to the major waterways of North Asia. It was not only the exploration of Siberia, which had been carried out along the rivers, but also control over it (Forsyth 1992, 39, 48, 54).

The waterways were supplemented by portages before the first overland highway was built in the late eighteenth century. The Siberian Post Road provided a stable West–East connection up to Baikal. From Irkutsk a major way led northeast along the Lena to Yakutsk, Okhotsk (Figure 1.2) (Glavnoe upravlenie počt 1914; Irkutskij gubernskij 1916; Morev 2010; Pereselenčeskoe upravlenie 1914f; Zabajkal’skij oblastnoj 1914), and then by sea to Kamchatka, Alaska, and the Aleutian Islands. The commodities from Siberia, North Asia, and North America were first transported to the Baikal region making Irkutsk a major trade center (Kationov 2004; Minenko 1990; Naumov 2006, 108–109).

Several overland routes connected the Baikal region to Central Asia, Mongolia, and China. The city of Troitskosavsk and two satellite trade settlements, Kyakhta on the Russian side and Maimaicheng on the Qing side, were founded after the Russian-Qing agreements of 1727. The agreements initiated dynamic trade relations between the two empires and their border regions. Tea gradually became one of the key commodities transported along the route connecting Kalgan, Kyakhta, Verkhneudinsk, Irkutsk, and Moscow (Figure 1.2). Trade in agricultural and manufactured products stimulated transboundary economic relations attracting many Russian and Chinese traders to the Baikal region, northern Mongolia, and Barga, the western part of Manchuria between the lakes Hulun and Buir and the Greater Khingan Range (Avery 2003; Lincoln 2007, 145–146; RGASPI 495–152–20, 43).

Figure 1.2 The Baikal region in the larger communication space.

Trade further intensified with the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway (Haptaev 1964, 23), which to a large extent followed the route of the Siberian Post Road up to Irkutsk. In 1899 the line connecting European Russia and Irkutsk was put into operation. Although with the completion of the CER in 1903 the Great Siberian Route connecting Saint Petersburg with Russian Pacific ports was officially finished, the space of the railway communication was interrupted by Baikal. Before the very expensive and technically complex Circum-Baikal Railway was put in operation in 1905 the gap had been bridged by two icebreaking ferries the Baikal and the Angara. The icebreaking capacities of the vessels enabled navigation only for a few days after the lake froze and in winter a cart road was set up to transport passengers, goods, and post (Sigačev and Krajnov 1998).

During the Russo-Japanese War the transportation capacity of the carts was not enough for military needs and rails were laid on the ice. The defeat in the war did not result in Russia losing the entire CER, but significantly challenged its security. The security of the CER was an issue already during its construction, as the railroad workers and guards were attacked by the Chinese population during the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901). It was therefore decided to build the previously planned route across Russian territory – the Amur Line – which was several hundred kilometers longer than the line through Manchuria and was partly situated in the permafrost areas. The construction began in 1907 and in 1916 the traffic between Petrograd and Vladivostok was launched (Sigačev and Krajnov 1998). A short narrow-gauge railway also functioned from 1897 in the gold-mining region near Bodaybo (Guzenkov 2004).

By 1917 the Trans-Siberian Railway provided a rapid and reliable connection between Europe and North and East Asia. The railway provided the empire with stable access to the Pacific maritime trade (Haptaev 1964, 37). The Baikal region occupied a central position in the space of railway communication. The Great Siberian Route’s major strategic parts, the Circum-Baikal Railway and the junction of the CER and the Amur Line, were situated here. The control over the transcontinental communication space depended very much on the control over the Baikal region (Gerasimova 1957, 28).

The increase in both traveling and transporting goods by the railway demanded improving both post roads and waterways in Siberia (Marks 1991, 205) in order to consolidate and diversify the communication space. The transportation space of the Baikal region was constituted by the railroad; post, country, and dirt roads; and waterways (Glavnoe upravlenie počt 1914; Pereselenčeskoe upravlenie 1914c; 1914f; 1914g).

Apart from transportation and traveling, the abovementioned networks provided information exchange. As of 1910 the Baikal region with its 178 postal settlements occupied top position in North Asia’s space of post communication, with the Irkutsk postal network being the largest in Siberia in terms of number of nodes and extent (Blanuca 2010). The post space of the Russian Empire extended from the Baikal region to the neighboring Qing territories after a private Russian post began operation in Urga in 1863. After the Russian post network in the Qing Empire became public in 1870 offices were opened in Beijing, Kalgan, Tianjin, Khovd, Uliastai, and Tsetserleg. Further offices were set up in Yantai, Shanghai, Lüshun (Port Arthur), Dalian, Harbin, Mukden, Urumchi, Hankou, and other places (Vladinec 2012).

Exchange of information also occurred by the telegraph which was laid along the Siberian Post Road in the nineteenth century. By 1864 the line connecting European Russia and Irkutsk via Omsk was complete. Irkutsk became the center of the telegraph network in eastern Siberia. In 1868 the telegraphic communication began in Chita, Nerchinsk, and Sretensk. The Siberian telegraphic mainline soon became the longest in the world. With the completion of the underwater cable from Vladivostok to Nagasaki and Shanghai in 1871 the Siberian telegraph provided almost instantaneous communication between Europe and East Asia. By the end of the nineteenth century the telegraph had completely ousted the post in business communication. The construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway further fostered the development of the telegraph and many stations were soon equipped with telegraph offices. The railway significantly lowered the maintenance costs of the Siberian mainline raising its competitiveness against the Indian line managed by the British Eastern Telegraph Company (Morev 2010). By 1917 the telegraph connected all major populated places of the Baikal region with European Russia, the Far East, and northeastern...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgments

- Note on transliteration, dates, and maps

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Demographics, economy, and communication in the borderland, 1911–1917

- 2 Transcultural spaces and entanglements, 1911–1917

- 3 The Buryat national autonomy, 1917–1918

- 4 Power struggle in a stateless context, 1918–1919

- 5 The Mongol Federation and the Buddhist theocracy, 1919–1920

- 6 The new independent states, 1920–1921

- 7 The Buryat autonomy in transcultural governance, 1921–1924

- Conclusion

- Index