![]()

Part I

Canons, Cultural Capital and Policies of Community Building

![]()

1 Nation Building and Children’s Literary Canons

The Israeli Test Case

Yael Darr

A Long – lasting Consensus

When referring to a literary canon in the field of adult literature, one usually points to a repertoire of texts, authors and literary models that enjoy a vast and enduring consensus with respect to their paradigmatic status and cultural significance. Such a canon is perceived as relatively stable, that is, resistant to changes in taste. In Pierre Bourdieu’s terms, that canon is located “beyond history” and therefore remains outside any intergenerational struggle over taste (Bourdieu, 1993: 112–113). According to Rakefet Sela-Sheffy, the field of literature requires a canon precisely in order to retain its dynamic features, its discursiveness and tentativeness. Canons remind us that all intergenerational disputes over taste – however strident – take place in a field that exhibits rules and a basic agreement between its participants (Sela-Sheffy, 2002).

The field of children’s literature is somewhat different, in the sense that it does not assume, a priori, overt intergenerational battles over taste. The master narrative of mainstream modern children’s literature does not sever the younger from the older generation but does precisely the opposite. In fact, it repeatedly reaffirms the structure of the family, stressing its benevolence and protection, as manifested by generational continuity (Darr, 2007).

We choose to read literary canons to our children because we seek the echoes of various intergenerational readings that resonate in each canonical work. These reverberations appear in two ways: at any given time (that is, knowing that the same text is being simultaneously read to a child by many others who share the national culture) and over time (that is, with the awareness that many others of that national culture have read this text to children throughout the years). In many cases, adults are emotionally and even nostalgically aware of those continuing intergenerational readings due to the fact that many had heard or read these same stories during their own childhood.

Regardless of the differences between both canons, we can perceive our choice to read and reread literary canons in adults’ and children’s literature alike as a ritual that celebrates generational continuity – within society. The canon, by its very existence, marks a joint between a nation’s cultural present and past.

All this applies to cultures of established and patent modern nation-states. This article deals with a different kind of literary canon, one which lacks an agreed-upon history of readership as it is constructed during a process of nation building. During these cultural starting points, the ‘nation’ and the ‘state,’ as cultural frameworks, are not yet taken for granted. As I will argue, canons are in great demand precisely for this reason: they provide the evolving national community with a common notion of a shared cultural past and present. The case study discussed in this chapter addresses the literary canon of the fledgling and most promising group at the time of nation building – that which is born into the emerging national culture and is expected to take it for granted: the children.

Inventing ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Literary Canons

During the 1980s, three pioneering sociological studies were published on the subject of nationalism and the modern nation-state: Nations and Nationalism by Ernest Gellner (1983), Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, by Benedict Anderson (1983) and The Invention of Tradition, edited by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (1983). All three refer to cultural beginnings and cultural fabrications: a phenomenon in which institutions, elites and cultural persona construct daily practices, a national history, tradition, festive rituals, folklore, etc. – all are required for the construction of the nation-state and its particular culture. These cultural inventions serve to enhance socio-cultural cohesion between the new nation-state’s citizens.

Among these intensive cultural initiatives inherent in nation building, the ‘invention’ of a children’s culture is especially important. In modern society, children point to the future, marking a cultural and national horizon. Cultural planners view young children as the first generation to receive the new national culture as a given. As opposed to adults, children have no “cultural memory” or cultural “habits.” They are therefore due to precede adults in the adoption of new national practices and cultural assets. These fresh carriers of the new culture can subsequently function as effective cultural agents in the present, both in the public and in the private sphere. They are further expected to continue to do so in the future, as adult members of society. It therefore comes as no surprise that in numerous cases of nation building, intensive canonization of children’s literature serves to construct the national child culture and its past.1

The literary canon of nation building seeks to compensate for the lack of historical readership by creating a sense of a national past. Nonetheless, it also stresses a new national beginning. Therefore, when dealing with nation building and literary canons, distinction should be drawn between older and more groundbreaking dimensions; that is, between what is presented as a traditional canon and the innovative, pioneering one. Significantly, the former creates a sense of durability, whereas the latter implies renovation and avant-garde; the so called traditional canon is meant to signify a mutual past, shared by members of the emerging national community, while the innovative one aims to denote a new culture and ethos which would be disseminated to the members of the infant nation.

As Hobsbawm showed, both canons represent instances of invention, by the mere fact that they combine the familiar with the new. However, whereas the traditional canon attempts to play down its invention, the innovative, pioneering canon overtly maximizes awareness of its new elements by playing down the old and familiar cultural components.

The Test Case of the Zionist Children’s Literary Canon

The period of Israel’s nation building refers primarily to the first four decades of the twentieth century. The study presented in this chapter extends this period well into the 1950s, refusing to view the establishment of the State of Israel, in 1948, as an abrupt end of this complex cultural phenomenon. The primary elites of the 1950s, who led the move from the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine) to the state in its founding years, were in fact the same elites that had managed the Yishuv prior to the state’s establishment; that is, the elite groups that were deeply involved in nation building during the 1930s and 1940s, maintained their leadership positions and preceded with their cultural initiatives during the first decade of the state.

Like numerous other cases, Zionism, which advocated Jewish national realization in Palestine invented or created its national culture and past. Nevertheless, the Israeli case stands out because the Yishuv’s Zionist culture avowedly negated its recent past and was overtly open to innovation. This was the culture of a first generation of immigrants, mostly Europeans, whose ideological perspective was grounded in the negation of the two major characteristics of most of its members: the Yiddish language and Jewish religion.2

Israeli Zionism preached new beginnings, which were in sharp contrast to the Diaspora: Hebrew was privileged over Yiddish, secularism replaced religious culture, a pioneering ethos took the place of traditional, conservative values and commerce was exchanged for manual labour and agriculture. Above all, the Zionist movement heralded the realizable present, in Eretz Yisrael in strong opposition to the Diasporic Jewish longing for a messianic future in the Holy Land.3

Due to the blunt negation of the Diaspora, the Zionist Jewish history that was narrated to children was founded on three chapters: the glorious biblical history of Eretz Israel (Land of Israel), “two thousand years of futile exile” and the current Zionist realization in the land of Israel. The Bible, as a mixture of national mythology and history, was portrayed as an indisputable canon. Of course, the same canonical text had served Jews throughout the Diaspora. Its invention resided in its innovative secular readings in Zionist Palestine.4

The use of Hebrew, the language of the Bible, as a spoken language in everyday life, was a means of reviving the ancient past and creating a sense of direct continuity in the national territory. However, in order to execute this task, Hebrew had to be reinvented as a secular spoken language. In this mission, children played a central role. They acquired natural Hebrew speech in kindergartens and schools, brought it home and taught the new ‘mother tongue’ to their immigrant parents.5 As a part of this great linguistic project, teachers and writers for adults produced numerous works for children as early as the first two decades of the twentieth century.6 However, only in the 1930s, after the Zionist Labor movement, Mapai, had established itself as a hegemonic elite, social conditions ripened for a deliberate and constant effort to dictate a literary canon aimed at the younger generation that grew up in Jewish Palestine and spoke native Hebrew.

The Innovative Canon: Emphasizing Radical Socialism

During the 1930s and 1940s, the strong Zionist Labor movement set out to create a children’s literary canon, which not only provided young readers with distinctly socialist poetics, but also offered selected Eretz-Israeli writings, which differed essentially from texts produced for children elsewhere in the world. This literature was meant, first and foremost, to serve as what was identified as a ‘new,’ innovative canon that emphasizes the revolutionary rather than the old and familiar. Its main characteristics were the following:

1 The protagonists were usually the young Sabra (Zionist native) and his or her peers. Parents, family and home were mostly absent from the plots.

2 The stories were located in the socialist formats of the Zionist settlement, those of the kibbutz and the moshav (a collective agricultural settlement), and addressed collectivist dilemmas. The plots revolved around the glorification of the communal upbringing, depicting the kibbutz childhood as the embodiment of heaven on earth. When a city-dwelling child appeared in these stories, his strong yearning for the kibbutz life was emphasized.

3 A negation of the Diaspora was a core principle in these texts. When a Jewish child living in Europe was presented, he (as he was usually male) was depicted as a temporary ‘other,’ who yearned to immigrate to Israel. Upon his arrival, sometimes after having left his entire family behind, he sheds all Diasporic traits and becomes “one of the Sabras.”7

These innovative and oppositional poetics for children often relied on literary models that won a canonical status in the West. The new Zionist values were overtly infused into these canonical forms.

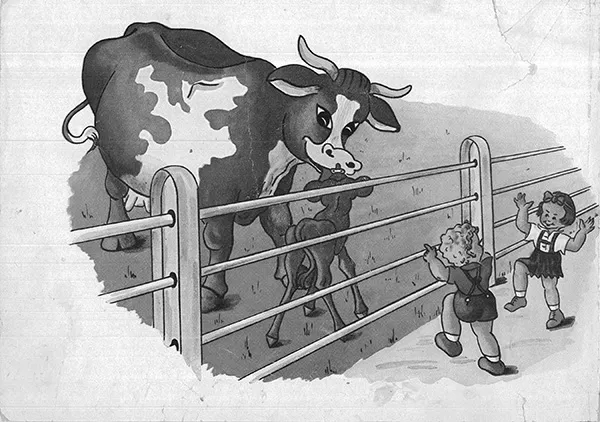

For example, Fania Berghstein’s Bo Elai Parpar Nechmad (Come to Me, Sweet Butterfly, 1945) was written according to the well-known literary model of ‘farm poems’ for toddlers. This literary model was comprised of a collection of farm images, usually focusing on animals, and consisting of pleasant, catchy rhymes that are easy to pronounce and memorize. The short rhymes are often employed to teach toddlers the different types of animals, their ‘homes’ (that is, pen, cowshed, henhouse) and the sounds they make (that is, braying, barking, roaring). This is the familiar and consensual component of Come to Me, Sweet Butterfly. However, the story bluntly replaces the original and neutral farm with the Zionist kibbutz.

The book’s front cover replicates the illustration that accompanies the first poem, the one that lends its title to the entire book (Figure 1.1). A girl is seen in the outdoors, her back turned to a house in the distance. She is facing a fenced-off plot of land where a butterfly rests on a flower. The child is dressed in typical kibbutz attire: shorts and no shoes, inadvertently suggesting that she feels at home even when she is outside. The illustration does not cover the entire page; it is enclosed by a colourful elliptic frame that transforms the open fields where the girl spends her time into a closed, bounded space. This type of a ‘home outdoors’ reflects the kibbutz notion that “the limits of one’s kibbutz are the limits of one’s home.”

The “me” that appears in the book’s title defines the narrator, as already encountered in the book’s cover, as a child who enjoys the kibbutz’s natural surroundings while simultaneously playing an integral part in the construction of that environment. The anonymous subject, a kind of ‘every-child,’ conforms to the canonical Zionist narrative that places a collective subject at its centre, with little left to the realm of the private or the individual.

Other illustrations in the book dwell on the fact that kibbutz children can wander around the kibbutz on their own, visiting iconic kibbutz sites: the chicken coup, the cowshed, etc. (Figure 1.2). The book’s final scene, the only one that takes place indoors, shows the child’s peer group – the kvutsa – retiring to bed, together, in the Children’s House, again – with no adult in sight. Instead, the children are bidden good night by “our watchful dog” (no page numbers in original), depicted as glancing in through the screened window, that is, he does not really share the children’s privacy (Figure 1.3).8

The Western literary version of this bedtime scene would involve a loving parent, caring for his or her child, usually in a cozy bedroom. Come to Me, Sweet Butterfly reflects the opposite values: a child’s independence is presented as far more advantageous than the bourgeois child’s dependence on his/her family.

An additional example of this novel Zionist-socialist writing, that relies on a canonical literary model, is Leah Goldberg’s, Dira Lehaskir (A Flat for Rent). This allegorical rhyming story for toddlers – a popular literary genre in the ...