![]()

1

Introduction

1.1 The Role of Technology

Technological innovations have changed the way we experience our private and business life. Physical innovations such as mobile communication technology allow us to connect directly with people around the world at any given time. The Internet facilitates the search and finding of information within seconds. Credit cards and online payment technologies facilitate the buying and payment of goods and services, independently of currency or country. High-speed trains reduce travelling times between metropolitan cities, increasing mobility and flexibility. Medical innovations have resulted in better treatment of diseases or even their prevention. Innovations in seeds and fertilizer technology allow us to grow more resistant, less water-consuming fruits and plants.

New ‘soft’ technologies have changed the way goods are developed, marketed and sold. Just-in-time production has reduced the required capital stock for goods such as mobile computers or automobiles, making them more affordable for consumers. Innovations in logistics have diminished delivery times and improved the flow of products. Management technologies such as total quality management or business process optimization have reduced production costs and increased the productivity of companies. New marketing techniques have provided a better understanding of consumer’s needs and increased client satisfaction.

However, not all new technologies have had a beneficial impact. The rapid and constant technological progress many countries have experienced has caused physical stress, the constant need to multitask and the inability to disconnect from work. Some technologies have also had adverse side effects such as pollution, destruction of environment, negative impact on health, or consumption of non-renewable natural resources.

Nevertheless, new technologies have overall contributed to increased living standards and economic prosperity. Life expectancy, average income and economic wealth have increased. New products and services have been developed, satisfying people’s needs in ways that were not met before.

Beyond its relevance for everyday life, technology is of crucial importance for the competitive advantage of firms and nations.

Firms create competitive advantage by inventing new products or finding new technologies to produce and market these. Access to abundant factors, such as cheap labour or resources, is becoming less essential than the technology and skills to produce them effectively or efficiently (Porter 1990: 14). For example, in the first decade of the twenty-first century, American automobile manufacturers have lost competitiveness not because of an unavailability of labour, equipment, or material resources. Rather their product technology, resulting in high fuel consumption, is falling behind European and Asian manufacturers, requiring them to slash prices and cut production. Amongst other factors, this has eventually resulted in the bankruptcy of several large US automotive manufacturers.

For nations, assuming that the principal economic goal is to produce a high standard of living, the only meaningful concept of competitiveness is national productivity (Porter 1990: 6; WEF 2009: 4). New physical or managerial technologies provide a competitive advantage by increasing productivity, setting the foundation for a higher standard of living. Factors such as cheap labour, investment in equipment and machinery, the availability of natural resources, low interest rates, favourable exchange rates, or low budget deficits by themselves do not sufficiently explain the long-term growth rates of successful economies (UNCTAD 2005a: 201). For example, nations such as Germany, Switzerland or Sweden have enjoyed rapidly rising living standards despite high wages, long periods of labour shortage and appreciating currencies. Countries such as Japan and Korea have prospered despite budget deficits (Porter 1990: 3). Economies such as Spain and Ireland have to import natural resources and have nevertheless outperformed nations with rich reserves in minerals, oil or gas.

Instead, technological advancements in the field of products and processes have driven long-term economic development. For example, Thailand has attracted manufacturing technology for its electronics industry, strongly contributing to its economic growth over the last decades (see Section 12.3 for details). The economic success of Korea has developed in line with its technological advancement, as measured for example by the number of patents registered (see Figure 1.2). Singapore has also been extremely successful in advancing its economic growth via the acquisition of new technologies in the field of electronics, biotechnology and banking (Box 1.1). Ireland, also referred to as ‘The Celtic Tiger’, has experienced substantial economic progress through FDI and advancements in its software and biotechnology industries (see Section 15.7).

Few if any countries have succeeded in achieving and sustaining high growth levels without investing in and exploiting new technologies (UNCTAD 2005a: 201). The importance of technology for economic development can therefore hardly be overstated.

BOX 1.1 SINGAPORE – A SUCCESS STORY OF TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER

With a population of about five million (2009), Singapore has shown impressive economic growth over the last years. Since 1980, real gross domestic product (GDP) has grown on average at 6.4 per cent per year, resulting in an increase of real GDP by close to six times. How could a small economy with no natural resources and domestic market achieve such a success?

A major driver has been technology transfer. Singapore went through four different phases of technological evolution (see UNCTAD 2003a: 50):

• Industrial take-off (early 1960s–mid 1970s). In this first phase, Singapore showed a high dependence on technology transfer from multinational corporations (MNC).

• Local technological deepening (mid 1970s–late1980s). The second phase was characterized by rapid growth of local process technological development within MNCs and the development of local supporting industries (clusters).

• Applied R&D (research and development) expansion (late 1980s–late 1990s). Later, a rapid expansion of applied R&D by MNC, public R&D institutions and local firms took place.

• High-tech entrepreneurship (late 1990s onwards). The last phase was characterized by the emphasis on high-tech start-ups and the shift towards technology-creation capabilities.

In these four phases, Singapore shifted from emphasizing technology use to technology creation, and each phase built upon resources accumulated in earlier phases. Skill creation, advanced infrastructure, strategic policy-making and efficient administration were key success factors in climbing up the technological ladder. Despite a free trade stance to attract FDI, the Singapore government was highly interventionist, deploying a battery of selective measures to support the technological evolution of the country. As a result of these measures, the country today ranks third in the world with regard to its global competitiveness.

(WEF 2009: 276).

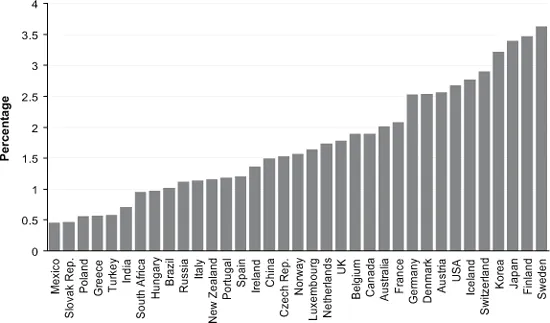

However, the gap in technological advancement between countries is large. For example, expenditure on R&D formulates a key indicator of government and private sector efforts to obtain competitive advantage in science and technology. Figure 1.1 illustrates the percentage of GDP large countries spent on R&D in 2007. Korea is the only newly industrialized economy among the top 15 spenders on R&D and China is the only developing economy among the top 20. With 3.4 per cent the industrialized nation Japan spent a more than seven times higher ratio on R&D than the developing country Mexico, with its 0.46 per cent of GDP. Given that the Japanese GDP exceeds that of Mexico by three times (valued at purchasing power parity – PPP), the gap is even wider.

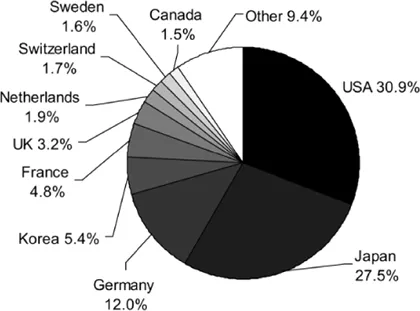

Similar observations can be made for the share countries hold in world’s registered patents (see Figure 1.2). Patents provide a measure of the output of a country’s R&D, that is its inventions. The top three countries, the US, Japan and Germany account for over 70 per cent of the world’s patents. There was not one emerging economy among the top 10 patent takers in 2006.

In order to bridge this technology gap, foreign sources of technology are of dominant importance for developing countries (Eaton and Kortum 1999). Channels to transfer technologies from these foreign sources are trade in products, trade in knowledge, or international movement of people, but one of the most important channels is foreign direct investment (FDI). Many economies seek FDI not only to attract finance capital: they are also interested in technology spillovers to domestic firms.

Figure 1.1 Gross domestic expenditure on R&D in 2007 as a percentage of GDP

Data source: OECD.

Figure 1.2 Share of countries in triadic patent families in 2006

Data source: UNCTAD. Triadic patent families are sets of patents taken at the European Patent Office, the Japanese Patent Office and the US Patent and Trademark Office.

1.2 The Aim of this Book

The importance of technology transfer via FDI implies that countries cannot simply sit and wait until new technologies arrive in their domestic domain. Rather, companies, regions and nations need to systematically manage the identification, attraction and absorption of new technologies.

This book wants to provide a practical guidance for companies (joint venture partners, local competitors, suppliers, buyers), government bodies (investment promotion agencies, investment boards, ministries of economics or ministries of science and technology), and multilateral organizations (development banks and agencies) on how to effectively attract, absorb and retain new technologies and knowledge via FDI. It aims to provide a step by step guide on how to manager the entire technology transfer process in FDI, starting with the development of a technology strategy, continuing with the assessment of technologies, their attraction, absorption and commercialization and ending with the controlling of the achieved technological progress. This book wants to support managers in answering the following key questions:

• What technologies should our region or country focus on?

• How can we get information on these technologies and assess their benefits, costs and unwanted effects?

• What can we do to attract investments containing these technologies?

• How can we facilitate the absorption of these technologies by our local companies?

• How can the companies in our country commercialize and use these technologies?

• How can we evaluate if we were successful in our efforts?

1.3 The Structure of this Book

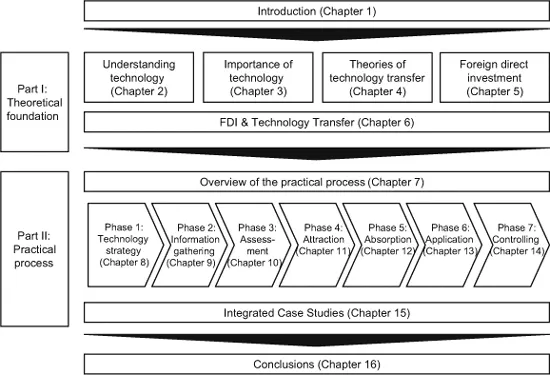

In order to achieve this aim, we have divided the book into two parts (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 The structure of this book

Part I (Chapters 2–6) provides the conceptual and theoretical foundations on technology transfer and FDI. We base our theoretical discussion on the economic literature, having studied FDI intensively, as well as the managerial literature, having intensively analysed technology and knowledge transfer:

• Following this introduction, Chapter 2 develops a clear understanding of the term technology, describes characteristics of technology and differentiates between various types of technology. In addition, it illustrates several mediums for technology storage and the various levels of technological capabilities a region or nation may posses.

• In Chapter 3, we deepen the understanding of technology by describing its importance for companies and nations with the help of managerial and economic theories.

• Chapter 4 lays out three different theories of technology transfer. These allow us to produce generic key factors for technology transfer depending on the type of technology to be transferred.

• Following this, in Chapter 5 we develop an understanding of FDI by describing historic and recent trends in this area, defining the term and identifying different forms of FDI. We then look at determinants of a firm’s investment decisions and the contribution of FDI to the local economy.

• Finally, Chapter 6 sets technology transfer in the context of fo...