eBook - ePub

Saint Cicero and the Jesuits

The Influence of the Liberal Arts on the Adoption of Moral Probabilism

- 182 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Saint Cicero and the Jesuits

The Influence of the Liberal Arts on the Adoption of Moral Probabilism

About this book

In this commanding study, Dr Maryks offers a detailed analysis of early modern Jesuit confessional manuals to explore the order's shifting attitudes to confession and conscience. Drawing on his census of Jesuit penitential literature published between 1554 and 1650, he traces in these works a subtly shifting theology influenced by both theology and classical humanism. In particular, the roles of 'Tutiorism' (whereby an individual follows the law rather than the instinct of their own conscience) and 'Probabilism' (which conversely gives priority to the individual's conscience) are examined. It is argued that for most of the sixteenth century, books such as Juan Alfonso de Polanco's Directory for Confessors espousing a Tutiorist line dominated the market for Jesuit confessional manuals until the seventeenth century, by which time Probabilism had become the dominating force in Jesuit theology. What caused this switch, from Tutiorism to Probablism, forms the central thesis of Dr Maryks' book. He believes that as a direct result of the Jesuits adoption of a new ministry of educating youth in the late 1540s, Jesuit schoolmasters were compelled to engage with classical culture, many aspects of which would have resonated with their own concepts of spirituality. In particular Ciceronian humanitas and civiltà, along with rhetorical principles of accommodation, influenced Jesuit thinking in the revolutionary transition from medieval Tutiorism to modern Probabilism. By integrating concepts of theology, classical humanism and publishing history, this book offers a compelling account of how diverse forces could act upon a religious order to alter the central beliefs it held and promulgated. This book is published in conjunction with the Jesuit Historical Institute series 'Bibliotheca Instituti Historici Societatis Iesu'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Saint Cicero and the Jesuits by Robert Aleksander Maryks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Early Jesuit Ministries

Ministry is the key word to understand who the first Jesuits were. Contrary to biased ideas circulating among scholars and being printed in many college textbooks, the Society of Jesus was founded to perform a defined list of consuetudinary ministries (consueta ministeria), such as ministries of the Word of God and works of mercy, but not to engage in academic education (“education of children and unlettered persons in Christianity” was quite different) or to counter Protestantism, which did become part of Jesuit activities, but only a decade after the order’s foundation in 1540. Even then, those consuetudinary ministries continued to be pivotal and were, thus, at the core of Jesuit self-understanding. As Loyola’s close associate, Jerónimo Nadal (1507–80), argued authoritatively, the Jesuit consuetudinary ministries did not evolve after the Society was founded, but determined its vocation and goal already at the Society’s inception.1

In order to interpret correctly the impact of the Jesuits on early modern Catholicism (some important aspects of which we shall track in this book) and beyond, it is necessary first to explore and analyze Jesuit documents that portray their self-understanding through ministries. This kind of hermeneutics, initiated by O’Malley in his The First Jesuits, challenges the approach of historians who study Jesuit history predominantly from the institutional perspective (Jesuit scholars included). But the history of Jesuit ministries, as we shall see, often shows a significant discrepancy between the Society of Jesus (and other religious orders) and ecclesiastical institutional developments that were often based on conciliar documents. In this context, historiographical periodization of sixteenth-century religious history into pre-Tridentine and post-Tridentine eras does not fully reflect the complexity and variety of Catholic initiatives of the period. The documents of the Council of Trent (1545–63) could have been barely helpful in the building of the Jesuit identity, for they focused on the hierarchical Church—Trent was a council of pastors and not of men religious.2 And the Jesuits were not pastors, if not when exceptionally coerced by the pope to except parishes or bishoprics in virtue of their special vow of obedience.3 Indeed, they usually excluded from their service those ministries that were typically performed by pastors: baptisms, marriages, and funerals. Trent did not address ministries (whose explosion characterized the period) if not that of preaching, but even that was treated in reference to bishops rather than to men religious. Trent did put a stress on the priesthood, but the first Jesuits identified themselves more by the type of ministries they performed than by their sacerdotal distinctiveness. Their religious identity came before the sacerdotal one. True, the final incorporation of a Jesuit into the Society was made not in virtue of his priestly ordination, but in virtue of his final religious vows.4 Nevertheless, the preeminent Jesuit ministry was administering sacramental confession, which was exclusively a sacerdotal ministry. Other ministries, such as spiritual conversation, preaching, sacred lectures, teaching Christianity, assisting the dying, missions to the countryside, or giving Spiritual Exercises, in which the first Jesuits indefatigably engaged—regardless of whether they were priests or not—were the satellites of the central ministry of sacramental confession, whose administrators possessed the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven.

Ministries in the Jesuit Formula Instituti

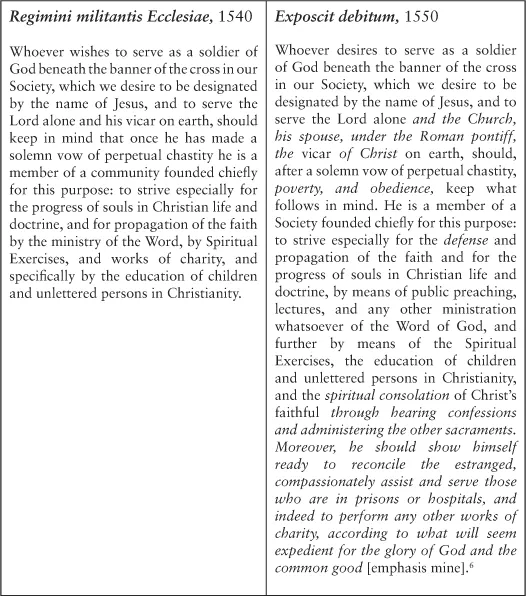

The importance of ministries results from the foundational document of the Society, Formula Instituti. It was a fruit of deliberations by Loyola and his first companions during their stay in Rome in 1539, after their plans of departing for Jerusalem to proselytize among Muslims had vanished due to the war la Serenissima allied with Charles V was unsuccessfully waging against the Ottoman Turks (1537–40). The goal of this ministerial manifesto was to draw the main features of this nascent religious group for papal approval. In its primeval version it was divided into five chapters and, therefore, known as Quinque Capitula. With some minor changes this document was incorporated into the papal bull, Regimini Militantis Ecclesiae (1540), which officially recognized the Society of Jesus as a new religious order. As the Jesuits were gaining their ministerial experience, Loyola and his close collaborators at the Jesuit headquarters continued to update the Formula. Its version that became part of the re-approval bull, Exposcit debitum (1550), of Pope Julius III testifies to a subtle yet significant shift in the Jesuit ministerial orientation within the first decade. Whereas the 1540 Formula indicated the Society’s goal as “the propagation of the faith and the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine,” the 1550 version added “defense” to the propagation of the faith. Yet, both versions indicated ministries by which that purpose had to be achieved. The latter Formula appended the mode that should characterize all the Jesuit ministries: they had to be performed without any financial reward (gratis omnino). It is noteworthy that in spite of the 1550 version’s adjustment, it does not betray any Counter-Reformation attitude, which truly did determine the spirit of the Council of Trent that was attended by a few yet prominent converso Jesuit theologians.5 A synoptic glimpse at the two versions of the Formula Instituti can be helpful in noticing the differences and similarities mentioned above.

There is nothing revolutionary about the list of ministries presented in both documents, for the Jesuits were heirs of a long medieval tradition that had had its roots in the IV Lateran Council (1215) and in the ministries of the mendicant orders. Yet, the Jesuits gave them a new importance and proposed a new way of performing them. This new style was non-traditional (praeter morem; [ministeria] insolita) and, thus, often encountered strong resistance (nimia circumspectio et cautela) within some ecclesiastical circles.7 One of the predominant features of this new style was the focus on spiritual consolation.

The Consolatory Character of Jesuit Ministries

Spiritual consolation had a very special place in Jesuit spirituality and ministries.8It had to permeate all ministries, as the Formula Instituti (quoted above) stated. Nadal explained well what the Formula meant by that:

These words—“especially spiritual consolation”—refer to all the primary ministries of the Society. They at the same time mean that we are not to be content in those ministries only with what is necessary for salvation but pursue beyond it the perfection and consolation of our neighbor. For spiritual consolation is the best index of a person’s spiritual progress. The word especially means that there are other ends we must pursue, but this one in the first place, as our primary intention and goal. If we do not have time and resources for both this and the others, we should omit doing them, and apply all our energies to this one.9

The same consolatory portrait of the Jesuit confessor is transparent in many other writings of the first Jesuits. Pierre Favre (1506–40), one of the very first Loyola’s companions, wrote in his spiritual journal, the Memoriale:

With great devotion and new depth of feeling, I also hoped and begged for this, that it finally be given me to be the servant and minister of Christ the Consoler, the minister of Christ the helper, the minister of Christ the redeemer, the minister of Christ the healer, the liberator, the enricher, the strengthener. Thus it would happen that even I might be able through him to help many—to console, liberate, and give them courage; to bring to them light not only for their spirit, but also (if one may presume in the Lord) for their bodies, and bring as well other helps to the soul and body of each and every one of my neighbors whomsoever.10

Nadal, the converso interpreter of Loyola’s spirituality, encouraged the Jesuit confessor to offer himself to the penitent with confidence as the sponsor of his conscience in front of God,11 to show magnanimity,12 and to exercise Christ’s and Church’s mildness (mansuetudo).13 The penitent had to be fed with a sweet hope, and his exhortations had to be done agreeably (suaviter).14 The Jesuit confessor was not only judge and physician—according to the terminology of the Councils of Lateran IV and Trent—but first of all father, because he substitutes for God-Father (pater et iudex in persona Dei)15—himself the omnipotent physician and compassionate Samaritan (ipse omnipotens medicus et misericors Samaritanus), who “pours wine of blame and oil of consolation with discretion, according to the condition of the penitent,” as a converso disciple of Juan de Ávila (1500–69) and later a Jesuit, Gaspar de Loarte,16 beautifully wrote.17

Juan Alfonso de Polanco was proud to refer in his Chronicon to the fact that the confessing ministry of Jesuits was so marked by its consolatory feature that people used to call them not Company of Jesus, but Company of Holy Spirit [the Consoler].18 Indeed, the Jesuits strove to bring consolation to their penitents as frequently as they could.

Frequent Confession and Communion

The most distinctive feature of the Jesuit paramount ministry of sacramental confession was their tenacious insistence on its monthly or even weekly frequency. The frequent confession campaign went far beyond the requirement established by the official Church—after the Omnis utriusque sexus of the IV Lateran Council (1215), that was reiterated by the Council of Trent during its session on Eucharist in 1551, all Christians were expected to communicate after having confessed all their serious sins once a year in private sacramental confession to their own pastor.19

The adamant call for frequent confession from ambones, convents, hospitals, prisons, streets, and squares would have invited devotes to receive the Holy Communion (Eucharist) more frequently, a practice that would later be abhorrent to the Jansenists, who never felt worth enough to communicate, even though frequent Communion was already practiced by the primitive Church that they glorified so much. To Jesuits the Communion was rewarding but it was not an award. It was rather a viaticus—Christ’s sustenance on the Christian pilgrimage in intimate con-union with Him.20 These two different anthropological visions would fuel the Jansenist-Jesuit controversy...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Publishers’ Note

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Early Jesuit Ministries

- 2 “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” Jesuit Ethics before the Revolution of Probabilism

- 3 “Christian Virtue and Excellence in Ciceroniam Eloquence” The Jesuit Literary Renaissance and Adoption of Probabilism

- 4 The Genealogy of Jesuit Probabilism

- 5 Probabilism as the Spiritual Sodom: Jansenist Attack Against Jesuit Ethics

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index