![]()

Part I

Overshadowed, Overlooked: Historical Invisibility

![]()

Chapter 1

Hidden in Plain Sight: Varano and Sforza Women of the Marche

Jennifer D. Webb

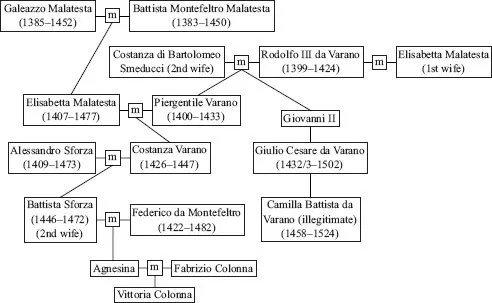

“Our time is not lacking in outstanding women who deserve praise,” remarked Ludovico Carbone (1430–85) in a wedding oration. “Who has not heard of Battista Malatesta, who delivered a fine oration before Pope Martin?” he continued.1 By posing such a hypothetical question, Carbone assumed that his audience was familiar with Battista Malatesta and other famous women who are now virtually invisible. Many hide in the shadows cast by their fathers or husbands while others, deserving of study, are ignored because the regions in which they lived are regarded as peripheral and provincial. This chapter explores the individual and group contributions of a dynasty of women born into the Sforza, Montefeltro and Varano families and living in Pesaro, Urbino, and Camerino. This dynasty helped redefine expectations for the role of women in a way that both colored the culture of the Marche and established a tradition of female education without rival in Italy.2 While these women did have greater opportunities than some of their peers, each woman was restrained by the opportunities available to her – often regarded as a forced choice between mental or physical clausura – and yet to some extent redefined her role and embraced her responsibilities. Each new generation built upon the advances of the previous and demonstrated further that Renaissance women, so often invisible in history, played a critical role in the culture of court and convent. Battista Montefeltro Malatesta (1383–1450) pioneered the education of women and played an active role in the ruling of the Malatesta court in Pesaro. Costanza Varano (1428–47) is famed for her role as poetess and advocate both for the rights of her family and for establishing educational programming in Pesaro. Battista Sforza (1446–72), Costanza’s daughter and subject of Piero della Francesca’s Diptych (c. 1472, Fig. 1.1) has one of the most famous profiles in Renaissance history and played a critical leadership role at the court of her husband Federico da Montefeltro.3 Battista’s second cousin, Beata Camilla Battista da Varano (1458–1524), the illegitimate daughter of Giulio Cesare da Varano, abandoned the luxuries of court life, withstood parental pressures to marry, and devoted her life to God by becoming a Poor Clare (female follower of St. Francis)4 (Fig. 1.2). These women, as well as their contemporaries and descendents, are not as renowned today as they were in their own age. Italian specialists have reviewed individual biographies but nobody has explored the contributions the dynasty made as a whole. Traditions of learning and leadership – that began with Battista Montefeltro Malatesta – deepened over the course of several generations and were realized completely in the life of Battista Sforza’s famous granddaughter, Vittoria Colonna. Each woman’s path is typical of those prescribed for the perfect Renaissance woman, but the subtleties of their individual biographies demonstrate that each found her voice and expressed herself with a vocabulary colored by her extraordinary humanist education and uniquely suited to her life.

1.1 Piero della Francesca, Diptych, front, portraits of Battista Sforza and Federico da Montefeltro, c. 1472, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

The question “Did women have a Renaissance?” was posed first by Joan Kelly-Gadol in 1977 and, over the subsequent three decades, the answers have become increasingly nuanced.5 While women did not benefit from the equality described so prosaically by Jacob Burckhart in The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, it is evident that certain women – both in courtly and Republican settings – found a way to make the best of the situation in which they found themselves.6 Like Isabella d’Este – famous for her interest in music, her leadership, and her patronage of artists like Andrea Mantegna – the Malatesta, Sforza, and Varano women were groomed for positions of relative prestige and power. Born into some of the most powerful regional dynasties, aspirations for each woman’s usefulness within a complicated system of negotiated allegiances was high as were expectations for rule and patronage. Many of these women would serve as regent or reign in their own right which meant that they needed to be as highly, if not more highly, educated than their husbands.7 As in the case of Barbara of Brandenburg, the wife of Ludovico d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, the consort often served as liaison with her natal family or as a conduit for information too important to be sent directly to her husband.8

1.2 Abbreviated family tree

In addition to serving in her husband’s name, a consort also took responsibility for the education of her children, the future dukes and duchesses. For this reason, it was essential that court ladies be familiar with classical writings and history, as well as be versed in Christian doctrine so that they could teach their sons, and daughters, the so cherished, and rather delicate, balance of the vita activa and vita contemplativa. As Florentine humanist Leonardo Bruni wrote in his 1424 treatise addressed to Battista Montefeltro Malatesta and concerned with the education of women, “the intellect that aspires to the best, I maintain, must be in this way double educated […] It is religion and moral philosophy that ought to be our particular studies, I think, and the rest studied in relation to them as their handmaids, in proportion as they illustrate their meaning.”9 Guided by Bruni’s humanist program, this dynasty of women established a tradition of humanist training that passed down through generations and which prepared their daughters well for the roles they were required to play at other courts. To understand the ways in which these women colored life in the Marche, one cannot focus on a single “extraordinary” woman but rather must consider the influence and interconnectedness of the dynasty as a whole in much the same way that scholars focus on the influence of the Medici family in conjunction with discussions of individual patrons.

Studies of fifteenth-century politics throughout Europe, but particularly in the Italian peninsula, focus on the importance networks of support and alliances played in fueling various power struggles and encouraging patronage. These networks – whether on the neighborhood, city, or regional level – were founded on links men forged in many ways, including through marriages and subsequent births, employment, political negotiations, and financial interdependence. Women, like their male relatives, also manipulated complex networks as an instrument for personal and familial gain as well as companionship.10 Unlike men whose participation in the vita activa was praised as a social responsibility, women looked to allegiances that emerged from the limited opportunities available to them; a woman could be a wife, mother, daughter, or pursue a religious career. Thus a woman’s network – which included sisters, cousins, mothers, aunts – extended from court to palace and into the convents with women like Battista Sforza who belonged to tertiary orders, providing the point of contact between women under clausura and those living a more “active” or public life.11 For Battista Sforza, like so many of her contemporaries, her networks converged to form a web that wove together those members of her family – including her great-grandmother, grandmother, and step-mother – who lived or had lived in Franciscan convents throughout the region with friends, family, and allies living at courts and in cities throughout the Italian peninsula.

Hidden in Plain Sight: The Legacy of the Visible yet Invisible Consort: Battista Montefeltro Malatesta and Battista Sforza

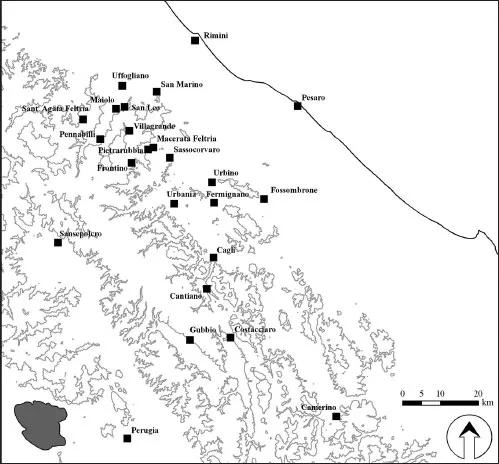

This dynasty of extraordinary women fully took root with Battista Montefeltro Malatesta for whom Battista Sforza, her great-granddaughter, was named. Born in 1384 to Antonio da Montefeltro, the then count of Urbino and the Montefeltro region (Fig. 1.3), Battista was baptized “Johanna Baptista” in recognition of her maternal uncle, Battista di Vico, and the family’s devotion to St. John the Baptist.12 She married Galeazzo Malatesta, heir to the signore of Pesaro, in 1405 and quickly became central to life at the court. Educated alongside her brother, Guidantonio da Montefeltro, at her family’s court in Urbino, her interest in the studia humanitatis matured further after she moved to Pesaro, a city with a rich tradition of artistic patronage and of learning that attracted humanists Coluccio Salutatio and Pietro Turchi.13 A deeply devout woman, Battista successfully balanced the vita activa and vita contemplativa. During the earlier years of her life she addressed diverse issues associated with rule and supervised, first, the proper education of her daughter, Elisabetta – born in 1407 – and later, that of her granddaughter, Costanza Varano.14 Bruni, a guest of the Malatesta court in Rimini in 1408, heard many praise Battista for her knowledge, grace, and devotion, a fact that he acknowledged in the opening of one of his least studied texts in which he established guidelines for the proper education of women.15 Although his text recognized the potential of women and encouraged them to study classical literature and history, feminist scholars criticize Bruni for discouraging women from becoming orators – a position regarded as the culmination of the study of classical literature and rhetoric – because it was an “arena” for men only.16

1.3 Map of the Marche region

Bruni opened his correspondence by praising Battista and then continued by citing historic examples of eloquent and literate women.17 While the references to Cornelia, Sappho, and Aspasia follow the model used in biographies of women, Bruni’s belief that they – and Battista in particular – should not be “satisfied with mediocrity” deviated from standard expectations for the ideal wife and reflected attitudes of the dynasty.18 He espoused a program that fused a keen study of literature – including poetry, prose, and oration – with that of history, a combination which was more typical of humanist regimens for the education of boys.19 The only area Bruni cites as being inappropriate for female participation is that of public oration; in his effort to demonstrate the absurdity of oral performance, he verbally paints the picture of a wildly gesturing woman and underlines the undignified nature of public presentation before concluding that “the contests of the forum, like those of warfare and battle, are in the sphere of men.”20 In her article, “Leonardo Bruni on Women and Rhetoric: De studiis et litteris Revisited,” Virginia Cox questions familiar interpretations of Bruni’s passage by arguing that Bruni is not speaking of public oration in general, but of women playing a role in a judicial setting, a possibility which Bruni regarded as both ridiculous and degrading.21 Cox supports her reading of the passage by pointing out the ironic tone adopted by the author – which distinguishes the section from the formal authorial voice found elsewhere in the text – and by addressing the completely unrealistic nature of such limitations, even for the Renaissance woman.22 Cox describes this tension as “a mismatch between scholastic prescription and courtly reality.”23 Bruni knew that societal constru...