eBook - ePub

Challenges of European External Energy Governance with Emerging Powers

- 402 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Challenges of European External Energy Governance with Emerging Powers

About this book

In a multipolar world with growing demand for energy, not least by Emerging Powers such as Brazil, India, China or South Africa (BICS), questions of EU external energy governance would at first hand appear to be a high-priority. Yet, reality tells a different story: the EU's geographical focus remains on adjacent countries in the European neighbourhood and on issues related to energy security. Despite being Strategic Partners and engaging in energy dialogues, it seems that the EU is lacking strategic vision and is not perceived as a major actor in energy cooperation with the BICS. Thus, political momentum for energy cooperation and joint governance of scarce resources is vanishing. Resulting from three years of international, interdisciplinary research cooperation among academics and practitioners in Europe and the BICS countries within a project funded by the Volkswagen Foundation, this volume addresses one of the greatest global challenges. Specific focus lies on the bilateral energy dialogues and Strategic Partnerships between the EU and Emerging Powers regarding bilateral, inter- and transnational energy cooperation. Furthermore, the analysis provides policy recommendations in order to tap the full potential of energy cooperation between the EU and Brazil, India, China and South Africa.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Challenges of European External Energy Governance with Emerging Powers by Michèle Knodt,Nadine Piefer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

European PoliticsIntroduction: EU-Emerging Powers Energy Governance

Chapter 1

Introduction

Energy issues are a priority topic in international affairs, especially with recent developments in Ukraine and Russia, and the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear catastrophe. Yet, for the international, interdisciplinary research project “Challenges of European External Energy Governance with Emerging Powers: Meeting Tiger, Dragon, Lion and Jaguar,” the starting point was an earlier scenario, which still has important repercussions for international energy diplomacy and energy governance. During the 2009 Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP) in Copenhagen, media coverage displayed desperate expressions on the faces of global leaders, such as German Chancellor Angela Merkel, French President Nicolas Sarkozy, and the President of the EU Commission José Manuel Barroso. On the other side, jovial faces from the Emerging Powers leading the negotiations—the BASIC coalition of Brazilian President Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva, South African President Jacob Zuma, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, and Chinese President Hu Jintao—demonstrated a change of power constellations and the importance of rising Southern powers. These images stand as pars pro toto for the current status of external energy governance and the challenges faced by the European Union:

• First, the establishment of a multipolar world order with Emerging Powers as major players and cooperation partners. Here, the challenge concerns the shape and structure of the relations that have evolved between the EU and Emerging Powers, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and on a transnational basis. The EU is losing ground in its relations with Emerging Powers, and still keeps to more traditional configurations of power, thus missing out in the complex multipolar world and its networked governance structure.

• Second, questions of global energy governance pose a challenge, as energy relations and energy governance take place in a highly dispersed environment. Neither a “World Energy Organization” has been established, nor is there political will to form one. The resulting complex, multi-level governance network is echoed in European energy governance, which is equally driven by a polyphonous institutional configuration.

This volume analyzes energy cooperation between the European Union and Emerging Powers in light of both these challenges. It consciously concentrates on the BICS (Brazil, India, China, and South Africa), and does not include Russia, because the EU’s relations with its main energy supplier differ significantly to those with other “consumer” states and are characterized by high interdependence. Reflecting the current changes of power relations as well as the global governance architecture in energy and climate governance, the BICS share a quality of acting as important diplomatic powers, “norm makers,” regional leaders, and valuable development partners—partners the EU as an increasingly global player can not live without. To add a geopolitical perspective, all of them are driven by rising energy demands, which in the cases of India and China leads to political pressure due to societal change and economic growth. At the same time, they all face the challenge of diversifying their energy sources by, for example, “greening” their energy mix, and thus are important partners on the quest for further decarbonization.

Research Design

The dependent variable (explanandum) we seek to explain is EU-Emerging Powers cooperation on energy issues, which we analyze by concentrating on the bilateral energy dialogues between the EU and each of the BICS countries. In order to explain the different shapes of the dialogues—which take place under the umbrella of the Strategic Partnerships—we draw attention to three main explaining factors embedded in different theoretical roots: institutionalist approaches and multi-level governance architecture, normative aspects, and actors’ interests, motivations, and perceptions. This model has guided the empirical case design, field research, and theoretical analysis throughout our project and forms the backbone of this volume. The multilateral and regional embeddedness of EU-Emerging Powers energy cooperation will be regarded here as a contextual factor.

With this design we endeavor to contribute to a two-sided and mutually complementary analysis of the energy dialogues between the BICS and the EU, as, to avoid Eurocentrism, our research is driven by a strong focus on mutual perceptions of the relationship between both partners. Furthermore, while chapters are written by different teams of authors, all draw on the same methodology, theoretical background, and empirical data provided in the research project.

Strategic Partnerships between the EU and Brazil, India, China, and South Africa (BICS)

The common political basis for the analysis in all chapters of this volume is the political instrument of Strategic Partnerships, which, as part of the European Union’s foreign policy, have been established between the EU and major global powers, including Brazil, India, China, and South Africa. Despite EU-BICS relations gaining increasing attention in academia, it remains a rather new research field and several research gaps can be detected. Indeed, energy as a specific area of cooperation has so far been overlooked.

In the literature it is claimed that: “The EU’s individual strategic partnerships with Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa are the most complex in terms of common goals, interests and global strategies” (Gratius, 2013, p. 2). This makes it a highly interesting and dynamic research field of ongoing academic importance, but while the Strategic Partnerships have been explored in several studies, a lack of comprehensive and in-depth analyses of these relations can be identified; an exception is Natalie Hess’s dissertation (2013).

Literature on the individual bilateral relations exists, however, this varies greatly among the BICS. A broad range of publications focuses on EU-China relations (see Gehler, Gu and Schimmelpfennig, 2012; Smith and Xie, 2010; Shambaugh, Sandschneider and Hong, 2008), but there is little on Brazil, India, and South Africa relations with the EU (on India, see Voll and Beierlein, 2006; Barbier and Mathur, 2008; on Brazil, see Whitman and Rodt, 2012; Grevi, 2013; Gratius and Grevi, 2013).

Bearing in mind not only the rise of South-South cooperation, but even more the diplomatic success stories Emerging Powers have written, for instance in international trade (Narlikar 2003; Oehler-Şincai, 2011), the EU and other countries run the risk of being marginalized. For instance, Renard and Grevi (2012a), focusing on climate politics as a specific policy field, conclude that there is a lack of linkages between the Strategic Partnerships and international negotiations on climate change (Renard and Grevi , 2012b, p. 9).

The EU’s search for a new role in a polycentric world has been an ongoing process, which affects not only the EU’s self-image and institutional structure, but also the way in which relations with other major powers are (re)shaped (Keukeleire and Bruyninckx, 2011). In order to enhance—or at present better maintain—its global role, the EU uses the Strategic Partnerships as a privileged mode of interaction with major Emerging Powers. In the aftermath of the Iraq war in 2003 and the crisis in the Trans-Atlantic relations between the EU and the US, the Strategic Partnerships were viewed in the EU as a tool to enhance “multilateral bilateralism,” in contrast to US unilateralism. For the BICS, a major motivation to engage in strategic partnership with the EU might have been the very recognition of a multipolar world order, and thus their status as major powers (Keukeleire et al., 2011).

Smith (2013) investigates more closely the EU’s role as an external actor and the current challenges attached to this. He states “[T]he EU’s approach and actions are now under question and challenged as never before, thanks to a concatenation of internal and external forces that has thrown into question the EU’s capacity to adapt to and profit from a reshaped world arena” (Smith, 2013, p. 670).

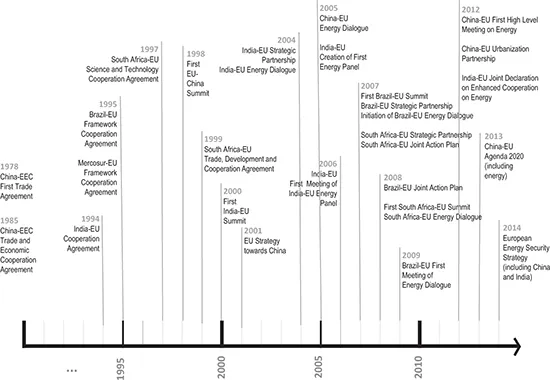

The EU is often criticized for its lack of strategic approach in its relations with the B(R)ICS (see Allen and Smith, 2012; Renard, 2010; 2011; Gratius, 2013). Grevi and de Vasconcelos (2008), in their analysis of the BRIC as potential partners to the EU in fulfilling its “effective multilateralism,” identify several challenges, especially the diversity among the BRIC, the EU’s lack of performance, and the diverging priorities between the EU and the BRIC (p. 155). Figure 1.1 provides a timeline of EU-BICS relations in general and of energy cooperation specifically.

Figure 1.1 Timeline of EU-BICS relations and energy cooperation

Source: The authors.

China and India were the first to be identified by the EU as important partners in the European Security Strategy (2003) and Strategic Partnerships were established at summits in 2003 and 2004. Keukeleire et al. (2011, p. 24) note, nonetheless, that the EU’s awareness of the potential and importance of India only increased at the turn of the millennium. In the case of Brazil, when trade relations with Mercosur began to stagnate, the Portuguese EU Presidency of 2007 expressed great interest in strengthening ties with Brazil, leading to the initiation of the EU-Brazil Strategic Partnership. As for South Africa, former President Thabo Mbeki was decisive in seeking stronger cooperation with the EU in 2007. The EU has meanwhile identified 10 countries as Strategic Partners and engaged in deeper cooperation with them: Brazil, Canada, China, India, Japan, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, and the United States.

Nevertheless, it has been widely pointed out that the EU still has no single, concise definition of what a “strategic” partner is (Gratius 2011, p. 1). Or as Herman Van Rompuy mentioned in opening the Council on Foreign Relations in 2010: “Until now, we had strategic partners, now we also need a strategy” (Council of the European Union, 2010). While this quote seems emblematic for the EU’s approach towards countries like India, Brazil, and South Africa, a distinct strategy in terms of political dialogue and economic cooperation can be detected in its cooperation with China. The weakness of the EU in this respect has its consequences on the BICS side. Keukeleire et al. identify the perceived value of the relationship as follows:

Now it is increasingly the case that BRICS countries are reluctant to recognize the EU as “a player” or “stakeholder” at all on many issues. Even worse, if the EU’s original idea was to coax the BRICS countries into its own framework of effective multilateralism, it has increasingly been forced to play ball with the game-rule preferred by the BRICS. (2011, p. 26)

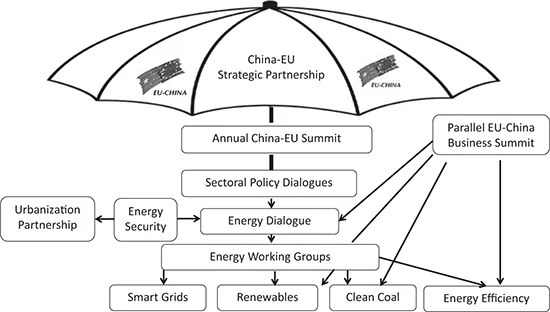

Nonetheless, Strategic Partnerships represent a relatively flexible instrument that allows intensifying cooperation and the opening up of dialogic arenas in order to facilitate communication between the two partners (see Chapter 10). Furthermore, they serve as an “umbrella” for deeper issue-specific cooperation in numerous thematic dialogues. The architecture of an energy dialogue can be illustrated by the EU-China partnership (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Structure of EU Strategic Partnerships (example of China-EU Strategic Partnership)

Source: The authors.

Within the scope of the annual summits between the EU and Emerging Powers (with parallel business summits for private sector involvement), different sectoral dialogues have been established; energy is among these. The energy dialogues are then again split into different working groups focusing on specific technical issues. The working groups are open (although only by invitation) to different non-state and public actors, NGOs, academia, and so on who can shape the agenda. According to some interview partners in Brussels (February 2012), generally three ways to enter the energy dialogues could be witnessed over time—here illustrated using the Chinese case. The first is a classical top-down approach, in which the Chinese President or Premier and the President of the European Commission decide on enhanced cooperation on a specific energy issue. The political decision is then transferred to the respective EU Commission Directorate Generals (DGs), who are responsible for the implementation of the dialogue. Second, a request from European industry can be expressed to the European Commission. A démarche to the Chinese ministries follows and then funding needs to be procured to enhance dialogue and specific cooperation projects. Third, a request may come from the Chinese side, for example the State Electricity Regulatory Commission (SERC), to learn from European experiences.

Over the years, energy dialogues have been able to connect political actors and promote a regular exchange of ideas. They have resulted in the creation of bilateral policy networks, which have been successful in (re)framing the political agenda and introducing new topics to the field of international energy policymaking. They serve as a flexible governance “tool” which allows for intense, tailor-made cooperation. Thus, exploring this governance arena provides rich insights into the governance architecture, normative orientations, and interests and mutual perceptions that the EU and the BICS actors keep.

Besides these bilateral arenas we take into account three other important dimensions of external energy governance:

1. bilateral energy relations involving EU Member States Denmark, Germany, Spain, and the UK and the BICS

2. the role of transnational energy companies

3. international energy governance and the embeddedness of the EU and Emerging Powers

Overview of Contributions to this Volume

This volume comprises seven parts, each addressing the same research question: How does external energy governance of the EU and BICS look and how can we explain it? Part I, besides this introduction, consists of a conceptualization chapter (Chapter 2) and a chapter introducing the explanandum—our research puzzle (Chapter 3).

In Chapter 2, Franziska Müller, Michèle Knodt and Nadine Piefer outline and discuss the theoretical framework used to empirically explore and analyze the field of international energy relations with Emerging Powers. Three analytical lenses develop a comprehensive view of different facets of international energy cooperation:

1. Institutionalist perspectives explain the structure of energy relations between the EU and Emerging Powers as well as the interplay between the European and Member State level, taking into account a multi-level governance approach.

2. In order to look “behind the scenes” of the formal dialogues and to focus on normative and discursive aspects, mutual perceptions, and external identities, the authors draw on different strands of constructivist thought, especially concepts of normative power and perceptions studies.

3. Interests and preferences in EU-Emerging Powers relations are significant explanatory factors, including those of public and non-state-actors from both the EU and the Emerging Powers.

Furthermore, this chapter introduces a mixed-methods design of qualitative interviews, a survey with 150 participants of the bilateral energy dialogues, and a quantitative network analysis.

In Chapter 3, Nadine Piefer, Michèle Knodt and Franziska Müller introduce the dependent variable, the research puzzle of this volume. Key facts of the bilateral energy dialogues between the EU and Brazil, China, South Africa, and India are presented together with an analysis of the interactions within networks that have evolved as a result of dense cooperation on energy issues. The main guiding questions for the analysis of this explanandum are: Who is...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- PART I INTRODUCTION: EU-EMERGING POWERS ENERGY GOVERNANCE

- PART II EUROPEAN ENERGY GOVERNANCE

- PART III EU EXTERNAL ENERGY RELATIONS WITH CHINA, INDIA, BRAZIL, SOUTH AFRICA

- PART IV COMMUNICATIVE CHALLENGES OF EU-EMERGING POWERS ENERGY RELATIONS

- PART V NON-STATE ACTORS WITHIN EU-EMERGING POWERS ENERGY RELATIONS

- PART VI MULTILATERAL AND REGIONAL EMBEDEDDNESS OF THE EU AND EMERGING POWERS IN ENERGY GOVERNANCE

- PART VII CONCLUDING REMARKS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

- Annex 1: Network Actors

- Index