![]() PART I

PART I

Antiquity![]()

Chapter 1

Omnis Caesareo cedit labor Amphitheatro, unum pro cunctis fama loquetur opus (Mart., 1, 7–8)

Manuel Royo

According to Brice Gruet, Rome can be considered as a “polycentric” city.1 A royal, then republican Rome, with the forum as its center, would thus substitute itself for the Palatine Roma Quadrata the sources mention.2 As demonstrated by Andrea Carandini,3 the shifting of the royal residence after Romulus’ reign from the Germal to the Northern corner of the Palatine Hill has played an essential role in the definition of a single center situated from then on between the Capitol Hill and the Palatine Hill.4 The doubling up of certain places (the mundus or the ficus ruminalis5), mentioned by the antiquarian tradition, has been challenged as a result of modern trends in source criticism.6 The invention and confusion of sources serve in reality as a confirmation of the recent archeological data. So, the mundus, which we identify with the umbilicus urbis, located not far from the comitium on the Forum,7 would respond to the Romulean templum, whose square altar marked the foundation deposit on the primitive site of the Palatine.8

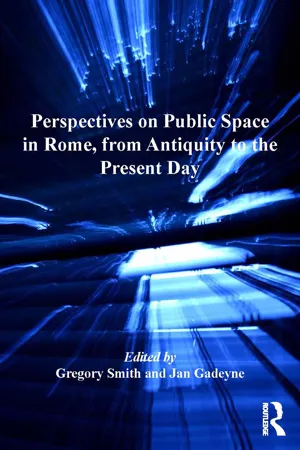

Figure 1.1 Rostra, Mundus and Umbilicus Urbis (from Ch. Hülsen, Foro romano, Roma, 1905)

The mundus on one side and the sulcus primigenius on the other9 are both witness to the fact that the foundation of a city corresponds to a religious rite which determines both its center and its periphery. According to some authors, the layout of the cardo and the decumanus, the two main axes which are to determine the zoning of the urban area, also depends on this rite.10

The center of a Roman city obviously has a religious definition and origins, but it also has an anthropological meaning, perceptible during certain festive rituals like the lupercalia, related to the foundation rites. They are a testimony of a “very lively process of a re-creation of the city and of an act of remembrance of this re-creation”: the heart of a city can be considered as “the focal point of a regularity, both social and spatial.”11

“By social regularity,” Brice Gruet understands “a kind of coherence which manifests itself by a will to make the different parts of society fit together, at least for the length of the celebrations; and by spatial regularity … the search for a correspondence at least metaphoric with the way a surveyor, for example, sees the world. The focal point of these regularities forms the key point of the city and the reason for its existence.”

Shifting the Center

We shall try to verify this definition by checking it against a rather surprising extract from Suetonius’ Life of Vespasian, in which the author makes the Colosseum the center of the Vrbs. Vespasian “has an amphitheater built in the center of the city after learning that Augustus had originally planned to build one”12 (item amphitheatrum urbe media, ut destinasse compererat Augustum).

This perception of a “shifted” center may be here a recognition of an anthropological reality, the origin of which merits discussion. Indeed, it cannot be a passing expression, since Suetonius presents, earlier in the text, the other monuments built by Vespasian. The Flavian reconstructions mentioned are not related only to the civil war of 69 AD. When Vespasian seized power, a big part of Rome had probably not been rebuilt since the fire of 64 AD :

Because of old fires and heaps of rubble, the city was ugly to see. Vespasian allowed anybody who wished to do so, to settle in the empty spaces and to build houses there, if the original owners did not. After he started to rebuild the Capitol, he was himself the first to get to work in order to clear away the rubble, carrying it on his own back. … He also had new monuments built: the temple of Peace, near the Forum, and the divine Claudius’ templum which Agrippina has started to build in the Coelian mount, but which had been destroyed nearly completely by Nero’s order. (Deformis urbs ueteribus incendiis ac ruinis erat; uacuas areas occupare et aedificare, si possessores cessarent, cuicumque permisit. ipse restitutionem Capitolii adgressus ruderibus purgandis manus primus admouit ac suo collo quaedam extulit … Fecit et noua opera templum Pacis foro proximum Diuique Claudi in Caelio monte coeptum quidem ab Agrippina, sed a Nerone prope funditus destructum).13

Topographically, the enumeration moreover respects to an extent the chronology of the restorations and of the new constructions: Suetonius starts with the Forum (with the temple of Peace) and, from there, moves on to the Caelian Hill and to the Temple of the Divine Claudius. Then he takes back the direction of the Capitol Hill and the Forum. Here Suetonius locates the Flavian amphitheater which, although it is more than 500 meters away from the entrance to the Forum, is said to be media urbe.

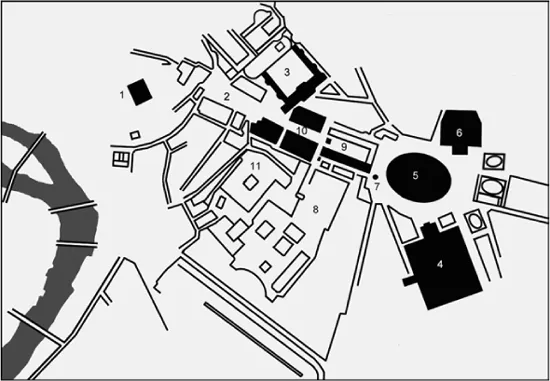

Figure 1.2 Flavian building activity and main monuments (© Royo drawing) : In black, Vespasian and Titus’ buildings; 1: Temple of Juppiter Optimus Maximus; 2: Forum Romanum; 3: Templum Pacis; 4: Templum Divi Claudii; 5: Amphitheatrum Vespasiani et Titi; 6: Titus’ Baths; 7: Meta Sudans; 8: ‘Vigna Barberini’ terrace (domitianic) and Domus Augustana Domitiana; 9: Atrium Domus Aureae; 10: Horrea; 11: ‘Domus Tiberiana’.

Stylistically, this phrase strengthens the feeling of singularity: not only is this formula rarely used in Latin literature (it is to be found about ten times concerning Rome14), but it is also mostly associated with the Forum, thus creating a redundant phrase highlighting its actual central position.15

An Anthropological Explanation

How can the Flavian amphitheater illustrate the social and spatial regularity and whose focal point would be this very building?

As a result of its own nature, the amphitheater welcomed, as soon as it was inaugurated, all the categories of the Roman population, without exception. But, unlike the Circus Maximus, where it was the custom for these categories to mix, the architecture of the Colosseum, which is similar to that of a theater, highlights the very organization of Roman society. Each member of the public can, by considering the seat he occupies in the cavea and the distinct journey he had to take to reach it, measure, mirrored in his position in the theater, not only the position he occupies in the social hierarchy, but also that of his fellow-citizens: the higher you are in the cavea, the lower you are in society.

As Eric Gunderson says,16 “Vespasian’s Rome is a society of the spectacle” and “the Flavian Amphitheatre is the site at which the play between image and reality is most profoundly negotiated without ever being decided in favor of the truth of the thing as against the speciousness of the image.” In this way, Rome makes a spectacle of itself and the “Colosseum became a didactic text of the operation of imperial power, a venue for the cultivation of ‘privileged visibility’ … and the promotion of a divine distance between the emperor and the Roman people, even as it suggested their congruence as participants in the power and empire of Rome.”17 The imperial figure is the focal point of this, and nearly the reason for its existence: “interestingly Martial’s choice of the editor or producer of the Colosseum’s inaugural games, Titus, as the dedicatee of his De Spectaculis, replays the circular semiotics of amphitheatrical spectacle: the emperor as origin and telos. … The arena became a theatrical solution to the political problem. Restaging the relationship between emperor and arena offered a visual display of the Flavian emperors as ‘a stable locus of political and cultural meaning.’”18 Ironically, “although the Flavian emperors used the arena to un...