eBook - ePub

EU Energy Security in the Gas Sector

Evolving Dynamics, Policy Dilemmas and Prospects

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

EU Energy Security in the Gas Sector

Evolving Dynamics, Policy Dilemmas and Prospects

About this book

This book fills an important gap in the literature on energy security in the gas sector in the European Union. Whilst the emphasis is often on energy security in the oil sector, the gas sector has grown in importance in recent decades, with increasing liberalization raising critical questions for the security of gas supplies. The share of gas in Europe's energy mix is rising and the differences between the politics and economics of gas and oil supply are becoming more pronounced. The author sheds light on the state of EU energy security in the gas sector, its interdependence with external suppliers and the current gas strategy. He examines the role of energy companies, EU member-states and EU institutions, locates the main developments in the gas sector and focuses on the principal challenges posed by such fundamental changes. The author scrutinizes the EU's relations with its main gas supplier, Russia, as well as with alternative suppliers, elaborates on the key infrastructure projects on the table and their principal ramifications, and discusses the main policies that member-states pursue to achieve energy security as well as the EU's internal contradictions. The book concludes with policy recommendations, particularly in the light of tougher environmental regulation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access EU Energy Security in the Gas Sector by Filippos Proedrou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Energy Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

It is the author’s conviction that this book should have been written for a previous era, not that of the beginning of the twenty-first century. Energy security should be based upon the extensive use of renewables, primarily solar, wind and geothermal energy and only to a limited degree upon fossil fuels. However, policy-making in general has been quite slow to comprehend the environmental challenge and reshape energy security towards a more sustainable mode. Despite all the innovations towards a green economy and sustainable development, it is widely assumed that no quick switch away from fossil fuels will take place. It is for these reasons expected that they will dominate the energy markets at least for the next few decades and that energy politics and economics will keep on revolving around oil and gas (IEA 2009: 4).

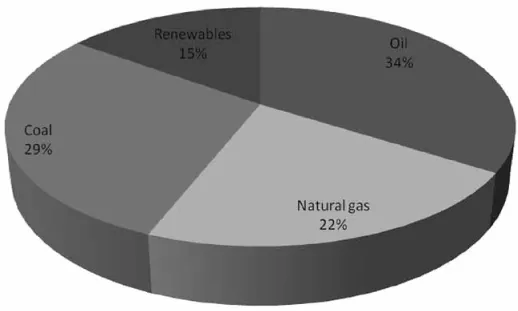

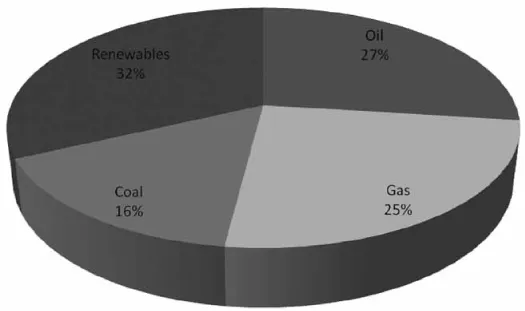

Fossil fuels account for more than three fourths of total global energy consumption. Oil is the basic fuel capturing around one third of overall global consumption, while the share of gas in world energy consumption has risen to more than 20 per cent. Coal is also widely used and accounts for more than one fourth of total global energy consumption. Its damaging effects to the environment, however, create strong grounds for a decreasing share in energy consumption in the mid-term. Moreover, coal is more of a domestic fuel, since only 10 per cent of its global production is being traded (Gros and Eigenhofer 2010: 2). Its weight in the global energy market hence is lesser than that of oil and gas. Renewable sources of energy (nuclear, solar, wind and hydro power and bio-fuels), though on the rise, only capture around 15 per cent of global energy consumption. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) (2009) and BP (2011) Energy Outlook for 2030, the global energy mix will change within the coming two decades. Oil and coal consumption are set to decrease, while natural gas consumption will further increase. The most important shift regards renewables, whose share will increase to around one third of total energy consumption. Despite this envisaged increase, however, fossil fuels are set to remain dominant in the mid-term. It is for these reasons that when talking about energy markets, energy policy and diplomacy, energy security and energy crises, reference is basically made to oil and natural gas.

What is Energy Security?

Energy is the backbone of all economies and the motor behind growth and development. We burn oil and natural gas to heat our homes, schools and hospitals, as well as light them. Transportation means run predominantly on oil. Coal and hydro power generate electricity and so do nuclear power, bio-fuels and solar, wind and geothermal energy. Without energy economies flounder, growth is suppressed and people will return to more primitive and less efficient and comfortable modes of living. It is for these reasons that energy security has been well incorporated into broader notions and strategies of national security.

Figure 1.1 The global energy mix

Sources: BP 2010, IEA 2010

Figure 1.2 The outlook for the global energy mix in 2030

Sources: IEA 2009, BP 2011

At the same time, oil and natural gas reserves are unevenly distributed. While a few states can supply their populations with domestic sources, the majority of countries, including the most developed economies of the world, have to import energy in order to cater for their energy needs. Ensuring adequate supplies then calls for imports from the more well-endowed states. Disruptions in energy supplies inflict grave concerns for growth, development, sustainability and survival. It is under this light that energy security is a central issue of global politics.

There is a bias in the literature to deal with the energy security of importers and not that of exporters. This is because most of the scholarly work done deals with the energy security considerations of the West, which is comprised mainly by importing countries. This book reproduces this bias since its aim is to examine an importer’s, the EU’s, energy security. Nevertheless, we have to sort out the different perspectives behind what exporters and importers perceive as energy security.

Starting with the importers’ perspective, energy security refers to that situation whereby states face no energy shortages and meet their energy needs at no excessive cost and without further deteriorating the state of the environment. It is the state whereby states ensure adequate energy supplies from reliable suppliers and at reasonable prices. It can be defined as:

• The guarantee of a stable and reliable supply of energy at reasonable prices (Qingyi 2006: 89).

• Securing adequate energy supplies at reasonable and stable prices in order to sustain economic performance and growth (Eng 2003: 4).

• Being driven by the need to secure energy supplies and deliver clean, affordable energy to combat climate change (Winstone, Bolton and Gore 2007: 1).

• A condition in which a nation and all or most, of its citizens and businesses have access to sufficient energy resources at reasonable prices for the foreseeable future free from serious risk of major disruption of services (Barton et al. 2004: 5).

• The reliable, stable and sustainable supply of energy at affordable prices and at an acceptable social cost (World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on Energy security cited by Yueh 2010: 1).

• The concept of maintaining stable supply of energy at a reasonable price in order to avoid the macroeconomic dislocation associated with unexpected disruptions in supply or increase in price (Bohi and Toman 1996).

For importers energy security means security of supply (that is sustainability of access to energy resources), pursuit of diversified sources of supply, suppliers and routes of supply to minimize risks and vulnerabilities stemming from any kind of dependence, at competitive prices and without harming the environment. Energy diplomacy, in this context, embodies the national effort to ensure the availability of energy at affordable prices (Kand 2008: 3). The contrary to energy security is energy poverty which can be defined as:

the condition where large swaths of a country’s population has inadequate access to energy supplies, suffering in particular by insufficient and unreliable access to electricity that would deprive them of the ability to service basic household needs (IEA 2008).

For exporters, on the other hand, energy security equates with security of demand at competitive prices that will guarantee significant profits for the exporter with no extravagant cost to the environment. Parallel interests for exporters include aversion of recession in importing states that will reduce energy demand, as well as aversion of switch to alternative sources and of diversification of suppliers. As Mares (2010: 9) puts it, energy security ‘embodies a claim for government action to protect national economic activity from shocks emanating from the international market’.

If we try to combine these two perspectives the most proper definition would be to see energy security as a ‘sound balance between energy supply and demand serving the purpose of facilitating sustainable economic and social development’ (Zha Daojiong cited by Tonnensson and Kolas 2006: 8) for both importers and exporters. By balance it is meant ‘the fit between a variety of energy sources and a complex set of needs’. This broader definition allows us to see the energy field as a system where both exporters and importers are active and satisfy their needs and, most importantly, their interests are not seen under a conflictive, as is usually the case, but under a cooperative prism (Dannreuther 2007: 91–2).

What is an Energy Crisis?

Failure to ensure energy security brings about an energy crisis. From the exporters’ perspective an energy crisis takes place when the exporter is unable to sell its energy at affordable prices so that it can pay off investment costs and create profits. However, the persisting thirst for energy means that such cases remain limited and marginal. Exporters in most cases find markets to sell their products, even if at times prices were lower than they would opt for. In the beginning of the 1980s, Algeria asked for high prices in order to supply LNG to the US and Spanish markets. The denial of the importers to comply with Algeria’s proposals led to the termination of trade for a few years. This led to Algeria sustaining financial damages. However, it still provided energy to alternative customers and one could argue that it was its own initiative to charge extravagant prices that led to these losses (Hayes 2006: 87–8). In the beginning of the 2000s, Russia also found itself in a similar position when Turkey announced that it could not absorb all the gas quantities that were contracted to flow through the Blue Stream pipeline that connects the two countries. As a result, Russia could not attain the profits it was estimating to raise through the function of the pipeline. Russia was, however, able to sell its gas to other consumers, thus facing no energy crisis (although the decision to build this pipeline proved a sub-optimal economic choice) (Hill 2005: 4–5). In the beginning of the 1990s the rise of domestic energy production in Argentina reduced the needs for gas imports from Bolivia. The Argentinean government then renegotiated the contract and secured smaller quantities at better prices. Bolivia was obliged to accept these deteriorated terms in the absence of alternative customers that would absorb its gas (Hayes and Victor 2006: 338).

Despite these incidents, it is far more frequent for importers to be denied supplies for a mix of political, economic and technical reasons. An energy crisis erupts when energy resources are scarce, when producers are (perceived as) unreliable or when the prices rise to an unsustainable level. These three risks are subsequently discussed.

The End of Oil (and Gas)?

Fossil fuels are not inexhaustible. The increasing consumption rates of the last decades have significantly narrowed the lifetime of oil, gas and coal. It is estimated that with current consumption rates oil will not last for more than four decades, gas for no more than seven, while coal will more than outlast another century (Gros and Eigenhofer 2010: 2). The discussion normally centres upon oil and its future availability since it is the dominant fossil fuel. A number of points made for oil, however, are also relevant for natural gas.

There are two schools of thought with regard to the exhaustion of fossil fuels, ‘peak theory’ and the theory of ‘super cycles’. Talk about the inevitability of running out of oil is not recent. The oil peak theorists claim that since oil is exhaustible, we will eventually run out of oil at some point. Oil deposits depletion is continuing at high rates, at the same time that consumption is at its highest with India and, principally, China, multiplying their oil imports in order to cover their mounting energy needs. Even if new deposits are discovered, we are heading towards the end of the oil era. Hence, we have to seek for alternative sources before it is too late (Deffeyes 2001, Checchi, Behrens and Egenhofer 2009: 11–12).1

To the contrary, a number of scholars appear much more optimistic about the future of fossil fuels. First of all, the oil price itself at any moment is a crucial factor for oil consumption rates and thus the lifespan of existing reserves. Low prices allow importers to consume further and act as disincentives for exploration schemes and new investments, since they are bound to yield marginal profits for the investors. This in its turn propels a period of tight supply that creates upward pressures to oil prices. Heightened oil prices then push investors to produce more oil to take advantage of higher margins of profit. This boom of oil investments influences the ratio between supply and demand in favour of the former thus serving as a new low prices initiator (Tonnensson and Kolas 2006: 57). The low prices of the 1990s had as a result less investments and thus declining supply for the following decade. For this reason and in combination with the rapid increase in energy demand, mainly stemming from South(east) Asian states as China and India, oil prices rose again and have now once more spurred energy companies to invest in oil exploration schemes in the 2000s.

Secondly, high prices drive importers to turn to a number of defensive measures. When faced with the oil crisis of 1973, an oil embargo and a four-fold oil price increase, importing nations adopted measures such as energy conservation and efficiency, lessening oil demand and switch to other, more economic fuels and suppliers. The use of natural gas was introduced, strategic deposits built up, overall demand for oil decreased and a policy of diversification away from overt reliance on Middle Eastern oil ensued. When in 1979 Iran’s Islamic revolution sparked the second oil crisis and new price hikes, importers were in a much stronger position than a few years earlier and withstood the crisis at much lesser cost. In other words, there are cyclical trends in the oil market, rather than a linear line leading towards exhaustion of reserves. This is why despite the century-old prophecies (dating back to 1880), the world still runs on oil (Odell 2004).

The discovery of a number of new fields in the previous years that significantly added to world reserves fortifies the above conclusion. High oil prices since the mid-2000s allowed more difficult and demanding exploration schemes to be realized. Deposits that were considered unprofitable to drill with a barrel of oil being priced at 9 dollars became highly profitable when the price of oil surpassed 100 dollars per barrel. Technological innovations also allow for more difficult, especially offshore and lying at great depth, fields to come on board. Unconventional forms of oil, like sand oil found in great quantities in Canada and heavy oil, create prospects for extending further the lifetime of oil (Odell 2004). Lastly, one also has to take into account that in case global warming keeps apace it may well transform the Arctic, where extensive oil and gas fields are estimated to be lying, into an explorable field (Borgerson 2008).2 What is even more important is that the drilling capacity does not surpass 30 per cent of overall oil quantities of wells. That means that there is significant space to improve the recovery factor and produce more oil from mature fields through advanced technologies (Pike 2010).

Gas is a newer fossil fuel than oil and takes up a lesser share in global energy consumption. Its lifetime is thus expected to be longer than that of oil. According to the James Baker Institute World Gas Trade Model (Jaffe and Soligo 2006) there is much potential for future gas production that will make up for the increasing gas consumption as projected in the following decades. In his study on European energy security Jonathan Stern (2002: 7) views gas reserves in the wider European area as lasting for more than a century. Besides the above estimations, one can easily apply similar arguments on the exhaustion or persistence of gas. Technological innovations, sweeping climatic changes and price volatility can well provide mechanisms for the postponement into the distant future of the end date for gas reserves. The discovery of significant reserves of shale gas in North America, as well as new gas deposits in the Eastern Mediterranean basin, is estimated to further extend the lifetime of gas (Geny 2010).

Are Suppliers Reliable?

Recent arguments regarding the end of the oil (and gas) era have turned emphasis from geology to politics. Even if, as the ‘super cycles’ theorists maintain, the end of the oil era is nowhere near, political instability pertaining to the oil market, the function of cartels, such as OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) and the strong hand governments retain in the property of oil and gas reserves,3 create a rather obscure picture for oil trade in the mid-term (Cable 2010: 75–82). One should not forget that both oil crises were provoked by political events in the Middle East, the Yom-Kippur Arab–Israeli war in 1973 and the Islamic Revolution and the subsequent establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran by Ayatollah Homeini in 1979. In the words of Yergin:

the major obstacle to the development of new supplies is not geology but what happens above ground: namely, international affairs, politics, decision-making by governments and energy investment and new technological development (2006: 75).

Indeed, a quick glance at the main producing areas reifies this point. The Middle East, which both produces the biggest quantities of oil than all other producers, as well as possesses most of the oil reserves, is a persistently unstable region, embittered by regional controversies of religious, historical, ethnic, economic and geopolitical character. At the same time, it consists of mainly undemocratic regimes with low rates of popular acceptability and raging economic and social problems that in a number of cases follow an opaque foreign policy and provide fertile ground for the nascence of fundamentalism. The ensuing political volatility, together with the function of OPEC, a cartel of producers comprising mainly the Middle Eastern producers (and some Latin American and African exporters), presents a ubiquitous danger for political and economic manipulations against the energy security of importers.

The former Soviet space is also plagued by similar problems. Military and dictatorial regimes form difficult, even if up to now proven reliable, partners. While the Caspian reserves have yet to be fully discovered and produced in significant quantities, Russia deserves special mention here for a number of reasons. First of all, it possesses one tenth of proven world oil reserves and more than one fourth of total gas reserves thus retaining a critical role in energy markets. Its predominance is especially pronounced in the gas sector bringing many actual and potential implications for the markets it provides. Secondly, it is one of the greatest powers of the world, thus frequently tying energy policy to wider foreign policy goals while also able to back these claims by force. Its ‘managed’ democratic system and state-capitalistic model of economic development has thwarted early expectations for open market and transparent energy relations and is viewed as problematic and perilous by many states dependent on Russian oil and, most importantly, gas (see Chapter 5).

Latin America is also a well-endowed but problematic region. Relations with the biggest oil importer and consumer, the US, remain opaque, not least because a number of its energy companies were pushed out of these countries. The return of the energy sector to state hands has raised concerns for the politicization of energy trade. In sum, Latin American populous democratic regimes create uncertainties to importing states with regard to the viability of their exports, as well as the rationale, trajectory and ultimate goals of the foreign policy they pursue.

One could argue that the situation in the gas sector is even bleaker. Beyond the predominant role of Russia as a gas exporter, Iran, the pariah state in the eyes of the West, comes second in world gas reserves. Other significant exporters are Malaysia and Indonesia, while small royal Arab states as Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) capture an increasing share of the market. Any significant increase in gas production can come from Central Asia, Africa and the Middle East, regions mostly governed by autocratic regimes and problematic leaderships (IEA 2010).

In this context, politics frequently jeopardizes the stability of the global mar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Maps

- List of Tables

- Notes on the Author

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Global Context and the Strategies of the Main Importing States

- 3 EU Energy Security: Tracing the Main Threats, the Policy Framework and the Actors

- 4 The Internal Front

- 5 Relations with Russia

- 6 Relations with the Other Producers

- 7 The Way Forward

- Bibliography

- Index