eBook - ePub

Dynastic Marriages 1612/1615

A Celebration of the Habsburg and Bourbon Unions

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The union of the two royal houses - the Habsburgs and the Bourbons - in the early seventeenth century illustrates the extent to which marriage was a tool of government in Renaissance Europe, and festivals a manifestation of power and cultural superiority. With contributions from scholars representing a range of disciplines, this volume provides an all-round view of the sequence of festivals and events surrounding the dynastic marriages which were agreed upon in 1612 but not celebrated until 1615 owing to the constant interruption of festivities by protestant uprisings. The occasion inspired an extraordinary range of records from exchanges of political pamphlets, descriptions of festivities, visual materials, the music of songs and ballets, and the impressions of witnesses and participants. The study of these remarkable sources shows how a team of scholars from diverse disciplines can bring into focus again the creative genius of artists: painters, architects and costume designers, musicians and poets, experts in equestrianism, in pyrotechnics, and in the use of symbolic languages. Their artistic efforts were staged against a background of intense political diplomacy and continuing civil strife; and yet, the determination of Marie de Médicis and her advisers and of the Duke of Lerma brought to a triumphant conclusion negotiations and spectacular commemorations whose legacy was to inform festival art throughout European courts for decades. In addition to printed and manuscript sources, the volume identifies ways of giving future researchers access to festival texts and studies through digitization, making the book both an in-depth analysis of a particular occasion and a blueprint for future engagement with digital festival resources.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dynastic Marriages 1612/1615 by Margaret M. McGowan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Frühneuzeitliche Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Political Context of the 1612–1615 Franco-Spanish Treaty

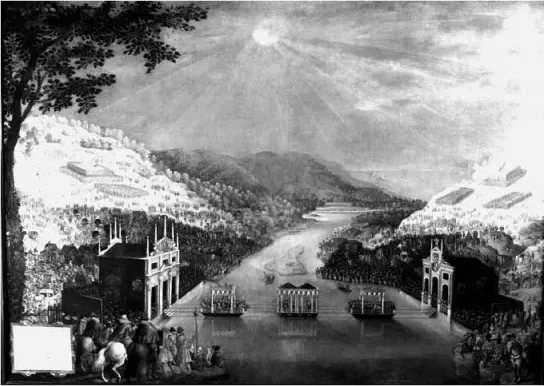

On Monday 9 November 1615 the Bidasoa river dividing France from Spain was the setting for a carefully choreographed ceremonial occasion of transcendent importance for European international relations. A double pavilion had been constructed on four barges, serving as pontoons, in the exact middle of the river. On each of the two river banks, where two other pavilions had been run up for the occasion, large bands of courtiers had congregated to witness the event. At an agreed moment, two canopied barges, attached to the shore and the river pavilions by cables, left the Spanish and French shores respectively for the river pavilions, where – again at exactly the same moment – the two principal figures disembarked with their entourages. One was the Infanta Dona Ana, the 15-year-old daughter of Philip III of Spain and the late queen Margaret of Austria; the other, the 13-year-old Madame Elizabeth, the daughter of Henri IV and his wife, Marie de Médicis, and the sister of the 15-year-old Louis XIII, king of France since the assassination of his father five years earlier.1

With the duc de Guise leading her by the hand, Madame Elizabeth, dressed in silver, proceeded towards the point where the two pavilions joined, while the Spanish Infanta, wearing gold and blue, and led by the Duke of Uceda, moved forward with equally measured steps to the nominal frontier line between France and Spain. Here the two suites were presented to each other and the princesses embraced. Then Uceda handed over Dona Ana (in future to be known as Anne d’Autriche) to the duc de Guise, who in turn handed over to Uceda Madame Elizabeth, henceforth Isabel de Borbón. After the exchange, and to the accompaniment of trumpets, drums and flutes, the two women proceeded in the reverse direction, Isabel to the Spanish side of the river, and Anne to the French.

Figure 1.1 Exchange of Princesses on the Bidasoa River, attr. Pieter van der Meulen (Monasterio de la Encarnación; Patrimonio Nacional, Inv. Nr. 06621531)

The exchanges, impressively coordinated, had been safely made, and marked the long-anticipated and much-deferred conclusion of many years of intensive diplomacy designed to bring about a reconciliation and lasting peace between the two countries whose rivalry had dominated so much of European power politics since the late fifteenth century – Valois, and now Bourbon, France, and Habsburg Spain. The process of reconciliation was to be formally sealed by a double marriage treaty, under the terms of which the Spanish Infanta would wed the young king Louis XIII, almost exactly her own age, while Louis’s sister, Madame Elizabeth, would become the wife of the heir to the Spanish throne, Philip, Prince of Asturias, three years her junior.

For much of the later sixteenth century their civil wars left the French too preoccupied with their internal dissensions to pursue a sustained and effective anti-Habsburg foreign policy. But the accession of Henri IV in 1589, and his abjuration of his Protestant faith four years later, marked the beginning of the restoration of order and stability in a war-torn country. Philip II had been actively intervening in the French religious wars in support of the Catholic cause and had been working to place his daughter, Isabel Clara Eugenia, on the French throne instead of the Protestant Henri de Navarre, but the new Bourbon ruler’s political skills, accompanied by his conversion to Catholicism, succeeded in rallying the mass of the country to his cause. In 1595 Henri declared war on Spain and successfully held Spanish forces at bay. In 1598, with Philip II bankrupt and nearing the end of his life, and France exhausted by its civil wars, the two countries made peace at Vervins. Five months later, Philip II died, and was succeeded by his young son, now Philip III, and as yet an unknown quantity.

The Franco-Spanish peace treaty of 1598 constituted part of a phased withdrawal from Spain’s heavy commitments in northern Europe – a withdrawal planned by a dying Philip II in the hope of leaving his son with a more manageable legacy until such time as the crown’s shattered finances could be restored. Peace with France was accompanied by a devolution of sovereignty over the Spanish Netherlands to Isabel Clara Eugenia and her husband, the Archduke Albert. It was hoped that this might in due course open the way to some sort of settlement with the Dutch rebels in the northern provinces, whose resistance had done so much to sap Spain’s military and financial resources. War with England continued, but the ageing queen could not last for ever, and war-weariness was taking hold in England as well as Spain.

At the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, therefore, Europe was slowly drifting back to peace, although the underlying tensions remained. At first it was not clear what direction Spain would take under its new king, Philip III. Philip himself seems to have been keen to show his colours by a display of activism, in the hope of winning a great victory at the start of his reign. The Spanish Council of State, affirming that ‘reputation is necessary at all times, and especially at the beginning’ of a new reign, opted for ‘offensive war’ as a device for frightening off Spain’s enemies and making the Spanish Monarchy respected and feared in the world.2 The need to maintain ‘reputation’, or, in modern terminology, not to lose face, was a constant theme of Spanish policy-making, but on this occasion the pursuit of reputation proved counter-productive. An attempted invasion of Ireland in 1601 ended in fiasco at Kinsale, although the reputation of Spanish arms was partially restored when the army of Flanders, under its new commander Ambrosio Spinola, captured Ostend in the autumn of 1604 after what had looked to be an interminable siege.

Since Kinsale it had been clear that Spain lacked the resources for a prolonged ‘offensive war’ on more than one front. The death of Elizabeth in 1603 and the accession of a pacifically inclined James VI of Scotland to the English throne provided the opportunity that both countries needed to resolve their differences. After intensive negotiations an Anglo-Spanish peace treaty was agreed in August 1604, and another of Philip II’s wars was brought to an end. One month later, Spinola’s capture of Ostend, followed by his spectacular campaigning successes against the United Provinces in 1605, held out the possibility, which would be seized on by the ‘Archdukes’ Albert and Isabella, for achieving peace with honour in the war with the Dutch.

Philip III’s instincts may have been in favour of war, but the deplorable state of the Spanish crown’s finances was against him, and his government was effectively in the hands of his favourite, the Duke of Lerma, who had other priorities, among which were his own survival in power and the enrichment of his family.3 His inclinations were all towards a quiet life. A general peace in Europe would allow time for the restoration of the crown’s finances and some restructuring and reform of the machinery of government. But peace in Europe did not depend on Spain alone. It also depended on the attitude and policies of Henri IV. Would the resurgence of France, now clearly under way, lead to a revival of the old Franco-Spanish rivalries and a new round of conflict, or could these dangers somehow be averted?

In 1601, taking advantage of the opportunities provided by the domestic difficulties of the two great powers, Pope Clement VIII broached the idea of a Franco-Spanish marriage alliance, just after the birth within five days of each other of the future Anne d’Autriche and Louis XIII of France. This happy conjunction of royal births seemed a providential event, holding out both the promise and the means for a general peace in Christendom.4 No matter that the two infants were scarcely more than a few days old, and that prospects for the survival of children – and especially of royal children – were notoriously precarious. Erasmus had long ago expressed his scepticism about the value and desirability of marrying off young princes and princesses as a device for setting the seal on peace treaties and diplomatic alliances. Dynastic inter-marriage, however, as an instrument of international power politics was and remained standard practice among the ruling houses of early modern Europe, and notoriously among the Habsburgs, whose current dominance owed much to the planned or fortuitous consequences of the complicated web of matrimonial arrangements that they had woven over the centuries.5

At the time when Clement put forward the idea of a Franco-Spanish marriage alliance, the age of the two royal infants made this little more than a glint in the papal eye. At this moment the rulers of both countries had more pressing priorities. Spain was still fighting England and the United Provinces. Henri IV of France was anxious to restore domestic tranquillity and counter the aggressive activities of Charles Emmanuel, Duke of Savoy, who had profited from the internal troubles of France to invade the French enclave of Saluzzo in the Piedmontese Alps, and, with Spanish support, had shown himself unamenable to reaching a settlement. With the help of papal mediation, France and Savoy agreed a peace treaty in 1601, but on terms that were widely regarded as unfavourable to French interests.6

The dilemma facing Henri IV after 1601 was that, after 36 years of civil war, he needed peace, but Spain remained hostile and continued to encourage the French malcontents. Together with the throne, Henri inherited traditional French fears of Habsburg encirclement. At several points the famous Spanish road, the military corridor along which the Spaniards sent men and supplies from Milan to Flanders, ran close to France’s eastern frontier, and – as seen from Paris – looked like a noose, although from the standpoint of Madrid the corridor appeared dangerously exposed to French attack. To counter-balance what he saw as the continuing threat from Spain, Henri needed to restore his country’s international standing. This meant casting himself as the credible protector of what the Venetians called the stati liberi, the chain of small independent states, several of them Protestant, running from the Adriatic to the North Sea, which owed formal allegiance neither to France nor the Habsburgs.7 It meant, too, financial assistance for the Protestant Dutch in their struggle against Spain, especially after James I had agreed, as one of the conditions of the Anglo-Spanish peace treaty, to abandon his predecessor’s policy of supporting the rebels.

A foreign policy tilted towards alliance with Protestant states required a delicate balancing act from a monarch who had recently converted to Rome, and had already tarnished his credentials by guaranteeing toleration for French Protestants in the Edict of Nantes. The delicacy of his situation makes it difficult to unravel Henri’s true intentions, but he was well aware that France needed a lowering of international tension.8 His interest was in peace, although ideally this was to be a pax gallica, peace on France’s terms, with France possessing room for manoeuvre if either the Austrian or the Spanish Habsburgs showed signs of aggression. Fortunately for Henri, by the middle of the decade the Duke of Lerma’s government found itself in serious trouble.

There was a fresh royal bankruptcy in Spain in 1607, and Madrid was left with no option but to approve the moves initiated by the Archdukes for peace with the Dutch – moves that would lead to the signing of a 12-year truce in 1609. In 1608, at this moment of acute difficulty, Madrid showed some interest in approaches from Henri for a Franco-Spanish marriage alliance, but the level of mutual distrust was too high and the negotiations stalled.9 As Henri contemplated possible alternative marriages for his children, including marriage alliances with England and Savoy,10 his relations with Spain and the Emperor deteriorated. They broke down over the succession question in the Duchy of Clèves, on the eastern border of the Spanish Netherlands, when the duke died without an agreed heir in 1609. In the opening months of 1610 Spain’s new ambassador in Paris, Inigo de Cárdenas, was reporting that war was almost inevitable.11 Henri was now actively preparing for military intervention in Clèves-Jülich and was struck down by Ravaillac’s knife as he was leaving Paris on 14 May 1610 to embark on his campaign.

Henri’s assassination changed everything. It left France with a nine-...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The Political Context of the 1612–1615 Franco-Spanish Treaty

- 2 A Time of Frenzy: Dreams of Union and Aristocratic Turmoil (1610–1615)

- 3 Festivities during Elizabeth of Bourbon’s Journey to Madrid

- 4 Celebrations in Naples and other Italian Cities

- 5 The Carrousel of 1612 and the Festival Book

- 6 The Carrousel on the Place Royale: Production, Costumes and Décor

- 7 The Ballet d’Antoine de Pluvinel and The Maneige Royal

- 8 Competition and Emulation: Music and Dance for the Celebrations in Paris, 1612–1615

- 9 The Dazzle of Chivalric Devices: Carrousel on the Place Royale

- 10 Literary Traditions and their Afterlife

- 11 Ambivalent Fictions: The Bordeaux Celebrations of the Wedding of Louis XIII and Anne d’Autriche

- 12 Firework Displays in Paris, London and Heidelberg (1612–1615)

- 13 The fêtes of 1612–1615 in History and Historiography

- 14 Dynastic Weddings in Personal and Political Contexts: Two Instances

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index