![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

The Scottish rural landscape is invariably a source of stimulation and an author needs little further encouragement. There are compelling physical features such as the richly wooded trough of the Dee, with its majestic backcloth in the smooth lofty Cairngorms, or sweeping vistas across the heather moorland and lonely lochans at Dava; each reflecting geology, climate, glaciation, river drainage or vegetation. They also generate distinct patterns of land use and questions about the reconciliation of the present system of exploitation with the need for conservation over the longer term. Such an awareness of time can then extend backwards into history for the geographer interested in settlement patterns, who may be fascinated by the various ways in which the land has been settled and managed through the centuries. How have perceptions changed with alterations in culture, technology and market conditions? Such issues have to be approached through documents but there are sufficient numbers of relict features surviving as fragmentary legacies of former lifestyles to show that the cultural landscape was significantly different in the past.

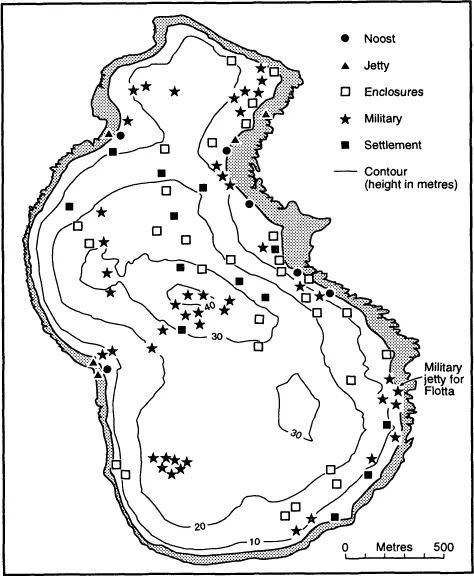

Such is the thrust of this book. It certainly cannot claim to be the first attempt to deal with the landscape through settlement patterns. After R.N. Millman’s general review of The Making of the Scottish Landscape in 1975 there have been more detailed surveys by R.A. Dodgshon on Land and Society in Early Scotland and by I. and K. Whyte on The Changing Scottish Landscape 1500—1800.1 In addition collections of essays edited by M.L. Parry and T.R. Slater in 1980 and by G. Whittington and I.D. Whyte in 1983 have discussed many salient themes in depth.2 However some of these works focused very sharply on agrarian issues and the Prehistory has received relatively limited attention despite a substantial amount of recent research which has called a number of established views into question.3 Moreover there have been a growing number of archaeological surveys (see example in Figure 1.1), often inspired by development projects such as afforestation that would destroy potentially valuable material, and these have helped to give an impression of settlement systems to supplement the in-depth studies of individual sites of the Skara Brae type.4 It has to be said that there is room for much more activity of this kind and, in particular, for fuller use of air photographs, before more reliable conclusions can be drawn about the stages of settlement evolution prior to the eighteenth century which the Roy Map and a substantial number of estate surveys are able to illuminate.5 Air photographs have been described as a particularly important (but grossly under-exploited) source for the reconstruction of early settlement patterns, especially in the Central Belt where so much of the archaeological evidence has been lost through modern settlement and industrialization.6 But the gaps in the record are being filled by hypothetical models of settlement evolution which are beginning to provide links between archaeologists and historians who are reaching out towards each other across the Dark Age and Medieval centuries.7

So there is scope for some kind of stocktaking with the continuity of settlement as the underlying theme. Continuity from the earliest times was once thought highly improbable because of the short periods of occupation indicated at many of the early sites investigated and dramatic changes in the nature of Prehistoric monuments which seemed to suggest radical cultural replacements as well as environmental changes which certainly rendered a number of sites untenable. But more sites are yielding evidence of occupation over prolonged periods of time while romantic notions of sequential occupation by invading groups of Neolithic, Beaker and Celtic farmers; followed up by broch-building pirates are giving way to more sober assessments about the scope for adaptation and political development by the indigenous population.8 The limited impact of the Romans and the growing evidence about the survival of Pictish culture in the face of Scottish and Viking assaults, once thought to have been quite overwhelming, offer pointers to possible prehistoric scenarios. An underlying continuity is now believed to be inherently probable even though conclusive proof is often lacking because of the continual process of adaptation in the face of technological, social and environmental change.

To avoid excessive overlap with work already available the links between settlements and agrarian systems are not given exhaustive treatment; and the survey goes only as far as the completion of the improving movement (c.1850). So many modifications have occurred since then – and been carefully studied – that a further book could well deal with the more recent trends in the development of the countryside. Again, there is no attempt to provide a comprehensive narrative of historical events although the basic issues are discussed. On the other hand there are attempts made to highlight specific sites in the text as well as through the illustrations and, while there is insufficient space to allow for a gazeteer and detailed locational information, attempts have been made to pinpoint locations on general maps of Scotland against a background of topography and administrative (regional) divisions. The further planning of visits may be expedited by the considerable number of guidebooks on the market. Several archaeological surveys either focus on the principal Scottish sites or deal with historic rural landscapes in general.9 These are complemented by a series of regional guides by the Commission for Ancient and Historic Monuments which are rather more accessible and convenient than the definitive surveys of monuments available for some of the former counties.10 A series of thematic guidebooks is available.11 And there is also a more substantial collection of books organized on a regional basis.12

Throughout the book there is an emphasis on sites in the Grampian region. To some extent this arises from the author’s familiarity with much of this area. But it is also evident that the Central Belt is poorly endowed with archaeological sites because of the high level of development which means that so much of the archaeology has been either destroyed or rendered inaccessible. By contrast the Highlands and Islands (which also receive considerable emphasis in the book) offer tremendous opportunities because of today’s sparse population and the decisive impact of environmental change in these relatively marginal areas. However, the greater detail for the northern regions should provide for more exhaustive assessment and raise issues which, for reasons of space, cannot be explored in all parts of Scotland. Other areas may be covered in greater depth with the aid of regional guides recently launched by two Edinburgh publishing houses. Chambers have covered the country in three books published in 1992.13 While Donalds have aimed more ambitiously at a major series covering much smaller areas. This was launched in 1986 and comprised six books during the first three years on areas ranging in size from Galloway and Inverness-shire to the Water of Leith.14 More recent publications have covered Aberdeenshire, Angus and Mearns, Argyll, Mull and Iona, Arran, Ayrshire, Black Isle, Dumfriesshire, Fife and the Pentland Hills.

Notes

1. R.A. Dodgshon (1981); R.N. Millman (1975); I. Whyte and K. Whyte (1991).

2. MX. Parry and T.R. Slater, eds (1980); G. Whittington and I.D. Whyte, eds (1983).

3. For example I. Armit, ed. (1990); W.S. Hanson and E.A. Slater, eds (1991); A. Small, ed. (1987).

4. For example RJ. Mercer (1980 and 1981).

5. See the Royal Commission for the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Scotlands survey of 1990 on ‘North East Perthshire’; discussed by J.B. Stevenson, ‘Pitcarmicks and fermtouns’, CA, XI (1991): 288–91.

6. G. Maxwell, ‘Aerial survey in South East Perth’, CA, XI (1992): 451–4.

7. W.S. Hanson and L. Macinnes, ‘The archaeology of the Scottish Lowlands: problems and potentials’, in W.S. Hanson and E.A. Slater, eds (1991): 153–66.

8. L. Alcock, ‘The activities of potentates in Celtic Britain AD 500–8000: a positivist approach’ in S.T. Driscoll and M.R. Nieke, eds, (1988), Power and Politics in Early Medieval Britain and Ireland (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press): 22–39; S.T. Driscoll, ‘The archaeology of state formation in Scotland’ in W.S. Hanson and E.A. Slater, eds (1991): 81–111.

9. R. Feacham (1977); L. Laing (1974 and 1976); E.W. MacKie (1975). More generally see G Summers (1990); K.A. Whyte and I.D. Whyte (1987).

10. Royal Commission inventories are available for Argyll (6 vols, 1971–82); Fife, Kinross and Clackmannan (1937); Galloway (2 vols, 1912–14); Lanarkshire (1978); Orkney and Shetland (3 vols, 1946); Peebles (2 vols, 1967); Roxburgh (2 vols, 1956); Selkirk (1957) and Stirling (2 vols, 1963).

11. D.J. Breeze (1987); R. Fawcett (1985); A. Ritchie (1988 and 1989); A. Ritchie and D.J. Breeze (no date); C. Tabraham (1986); B. Walker and G Ritchie (1987).

12. J.R. Baldwin (1985); J. Close–Brooks (1986); A. Ritchie (1985); G. Ritchie and M. Harman (1985); I.A.G Shepherd (1986); GP. Stell (1986); J.B. Stevenson (1985); B. Walker and G Ritchie (1987). Shorter studies are also available on Iona (J.G Dunbar and I. Fisher, 1983) and St Kilda (GP. Stell and M. Harman, 1988).

13. S. Bathgate, South West Scotland (Edinburgh: W. and R. Chambers, 1992); R. Smith, Highlands and Islands (Edinburgh: W. and R. Chambers, 1992); C. Woolenough, Central Scotland (Edinburgh: W. and R. Chambers, 1992).

14. A. Coghill, Water of Leith (Edinburgh: Donald, 1988); W.F. Hendrie, West Lothian (Edinburgh: Donald, 1986); L. Maclean of Dochgarroch, Inverness-shire (Edinburgh: Donald, 1988); I. Macleod, Galloway (Edinburgh: Donald, 1986); J. Shaw Grant, Lewis and Harris (Edinburgh: Donald, 1987); I. Whyte and K. Whyte, East Lothian (Edinburgh: Donald, 1988).

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

The physical environment

The Scottish environment requires some consideration because it provides a varied resour...