Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to reconstruct Keynes’s theory of monetary policy, as stated in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). Keynes’s theory is composed of three concepts—namely, the investment multiplier, the marginal efficiency of capital, and the interest rate. By analyzing how these three concepts interact in the short period, Keynes explains why he is opposed to efforts by the Federal Reserve to stabilize the economy on a non-inflationary growth path, or countercyclical monetary policies. And by analyzing how they interact in the long period, he explains why the economy tends to fluctuate around a long-period equilibrium position that is characterized by unemployment. Keynes concludes that central banks should “buy and sell at stated prices gilt-edged bonds of all maturities” to dislodge the economy from its tendency toward a long-period equilibrium position that is characterized by unemployment and propel it toward a long-period equilibrium position that is characterized by full employment.

This is not what orthodox economists believe central banks should do. Some orthodox economists argue that central banks should concern themselves exclusively with inflation (or the rate of change of the price level), decreasing and increasing the stock of money according to whether inflation is above or below a target rate of about 2 percent (see, for example, Bernanke et al., 1999). Others argue that central banks should also concern themselves with unemployment, decreasing and increasing the stock of money according to whether the economy is growing above or below a rate that corresponds to a non-inflationary rate of unemployment, which is estimated to be somewhere between 4 percent and 6.5 percent (see, for example, Blinder, 1999).

In this chapter, I argue that the difference between Keynes’s theory of monetary policy and the orthodox one results from the fact that they characterize the persistent and systematic forces at work in the economy differently. In other words, the long-period equilibrium position is not a fixed point, a stationary state, or even a steady state. It is simply the position toward which the persistent and systematic forces at work in the economy, at any given moment, are tending. When these persistent and systematic forces change, so does the long-run equilibrium position (see, for example, Halevi et al., 2013).

In orthodox theory, monetary policy is not one of the persistent and systematic forces at work in the economy, nor are any other financial or monetary variables. Financial markets and institutions only cause short-period fluctuations of the economy around an equilibrium position determined by other forces in such a way that it is characterized by full employment. In contrast, for Keynes (1936, p. 254), monetary policy, and financial markets and institutions in general, are persistent and systematic forces that contribute to the determination of the economy’s long-period equilibrium position is such a way that

we oscillate, avoiding the gravest extremes of fluctuation in employment … in both directions, round an intermediate position appreciably below full employment and appreciably above the minimum employment a decline below which would endanger life.

In Section 1.1, I explain the persistent and systematic forces that propel the economy in the orthodox theory of monetary policy. In Section 1.2, I then counterpose the long-period equilibrium position of the economy as determined in orthodox theory with the one determined in Keynes’s theory. In Section 1.3, I provide a summary and conclusions.

Section 1.1 The Orthodox Theory of Monetary Policy

The orthodox theory of monetary policy is derived from the Quantity Equation, which can be written as follows:

where M is the stock of money; V is the velocity of money; P is the price level; and Y is the equilibrium level of aggregate output. It follows that PY is the equilibrium level of nominal income.

Equation 1.1 is an identity. That is to say, nominal income (PY) is defined as the monetary value of all final goods and services produced and sold within a country within a given time period. Consequently, it must be exchanged for money. But each unit of the stock of money (M) may be used in more than one transaction during the time period in question. The number of such transactions is what is meant by the velocity of money (V). Therefore, PY must, by definition, equal MV.

Orthodox economists transform the Quantity Equation into a theory of monetary policy by making two assumptions and one causal claim—namely, that the equilibrium level of aggregate output (Y) and the velocity of money (V) are constant and causality runs from changes in the stock of money (M) on the left side of Equation 1.1 to changes in the price level (P) on the right side.

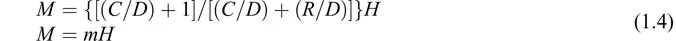

Given this theory, orthodox economists need only introduce the money multiplier to explain how the Federal Reserve determines inflation (i.e. changes in the price level), which can be derived as follows:

where H is the monetary base, or high-powered money, which can take the form of either currency in circulation (C) or bank reserves (R); and M is the stock of money, which can take the form of either currency in circulation (C) or demand deposits at banks (D). If we divide Equation 1.3 by Equation 1.2 and rearrange terms,1 we obtain:

or:

where the parenthetical term m is the money multiplier, or the ratio of the stock of money (M) to the monetary base (H).

On the basis of Equation 1.4, orthodox economists argue that the stock of money (M) is determined by:

- the public’s decisions to hold currency as a proportion of demand deposits (C/D);

- the banks’ decisions to hold reserves as a proportion of demand deposits (R/D); and

- the monetary base (H).

Studies by Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz (1963), Phillip Cagan (1965), and Allan Meltzer (1969, 1982, 2003, 2009), among others, suggest that in long-period equilibrium changes in the monetary base (H) account for 90 percent of change in the stock of money, with changes in the reserve-deposit ratio (R/D) and currency-deposit ratio (C/D) accounting for the rest.

About 70 percent of the monetary base is supplied through central-bank open-market purchases of securities or direct lending to banks (see, for example, Burger, 1971, p. 19). Since the Federal Reserve has reliable information on the other factors supplying the monetary base,2 it appears that the Federal Reserve can control the monetary base and thereby control the stock of money (the money multiplier itself can be forecast with a small margin of error (see, for example, Rasche, 1972; Johannes and Rasche, 1981)).

However, I present evidence in Chapter 3 that this appearance is false. These orthodox economists assume that the banks passively accept the discipline implied by the Federal Reserve’s alleged control the stock of money because they are unwilling to risk insolvency by overextending themselves and granting more loans than can be sustained by the reserves the Federal Reserve supplies. But the banks are not passive in this way. They are dynamic economic agents, aggressively pursuing profitable lending opportunities, creating bank deposits in the process, and only looking for reserves later (see, for example, Holmes, 1969, p. 74). If the Federal Reserve refuses to supply the required reserves under these circumstances, it will precipitate a financial crisis. As Thomas Palley (1987–8, pp. 382–3; also see Moore, 1979, 1988, 1989; Wray, 1998, 1999) puts it:

Though the monetary authority may deny [discount] window access to any single bank, in the event of generalized reserve shortages arising from collective overlending by banks, it cannot deny access to the banking system as a whole without generating financial cris...