![]() PART I

PART I

The European Union with(in) International Organisations: Broader Pictures![]()

Chapter 1

Methodology. Studying the EU’s Long-term Participation with(in) International Organisations: Research Design, Methods and Data1

Anne Wetzel

Summary

The study of the European Union’s (EU) relationship with IOs has recently been gaining increased attention. This chapter reflects on some challenges that researchers have to tackle when addressing questions concerning causes, forms and effects of the EU’s long-term participation with(in) IOs. Its aim is to highlight and explicate some of the research steps that are fundamental to the study of the questions raised in this edited volume. In so doing, it intends to sensitise readers to make reasoned decisions in the process of their own research on the EU’s long-term participation with(in) IOs. Following specification of the participation concept, this chapter refers to issues related to outcome-centric research designs (linked to the question of why and of how the EU is engaged), and issues related to factor-centric research designs (linked to the question of the effects of long-term participation). The chapter finishes with suggestions on the use of quantitative methods as a way to complement qualitative research.

Key Words

Case study; causal inferences; concept specification; factor-centric; outcome-centric; research design; selection bias; variables.

Introduction

The study of the European Union’s (EU) relationship with international organisations (IO) has recently been gaining increased attention (see the introduction to this volume). This edited volume adds the particular aspect of the EU’s long-term participation with(in) IOs and addresses the three concrete research questions of why the EU is engaged in the long term with(in) IOs, the form this engagement takes, and what effects it has – both on the IOs and the EU itself. With regard to these research questions, several challenges related to research design, methods and data have to be tackled by researchers. This chapter addresses some of these issues by proposing research methodologies adapted to each of the three questions contained in the present volume. To illustrate the methodological points made here, it also draws on personal research conducted on the EU’s status in IOs2 and on the contributions to this book. At the same time, the chapter does not attempt to provide any single ‘recipe’ of how to build one’s research design. All decisions related to conceptualisation, methods and data eventually have to be made with a view to the researcher’s particular question. Thus, any concrete suggestions or references to chapters merely serve to illustrate the general points, and are not the only valid way to go. Moreover, this chapter relates to a positivist research tradition: this does not imply, though, that other research traditions, such as interpretative approaches (e.g. Yanow 2009), cannot offer valuable insights into the question of the EU’s long-term participation with(in) IOs.

The next section discusses the issue of delimitating the core concept of the present volume, i.e. participation. A second section then explains how an outcome-centric research design is useful for addressing the first and the second questions of this volume (i.e. how and why the EU participates in the long term). A third section details how a factor-centric research design is relevant for dealing with the third question raised (i.e. the effects of long-term participation). The conclusion proposes to go one step further and, by building on this publication and on other future researches, to engage in quantitative analysis of the participation of the EU in different IOs.

Concept Specification: What is Participation?

The notion of the EU’s long-term participation with(in) an IO is central to this edited volume. In the case of the first and the second research questions, it is the dependent variable, i.e. the phenomenon that is to be explained. In the third research question, it is a key independent variable. In all three cases, this notion has to be defined. ‘Long term’ has been defined in this volume as a ‘duration of more than a decade’ (see introduction to this volume), but what is meant by ‘participation’? While this may sound trivial, participation can mean very different things (Frid 1995: Chapter 4). Is it certain types of long-term activity or strategy? Is it related to decision-shaping and making? Is it about material or immaterial contributions to an IO? Does it have to be distinguished from representation, i.e. the ‘question which institution or person is entitled to speak’, as some scholars suggest (Dutzler 2002: 153)?

The problem of defining what is meant by the variable ‘participation’ relates to the issue of concept specification, i.e. ‘the process by which a researcher defines and explicates the attributes of the concepts she uses in her research’ (Wonka 2007: 42–3). It is a crucial and early step in the research process since ‘[t]he validity of empirical and causal inference … depends crucially on properly specified concepts’ (Wonka 2007: 41). Without clearly specified concepts it is difficult to make sense of and compare research results (for some practical guidelines, see ibid.: 50–3).

One can identify a whole range of understandings of participation in this book alone. Most of the contributors consider it as dependent variable for the first two questions of why and how, and then as an independent variable to explain the effects of the EU with(in) IOs. A first possible understanding of participation relates to the EU’s status with(in) IOs (meaning not particular activities but the context for such activities: Grabitz 1975, Hoffmeister 2007, Jørgensen and Wessel 2011, Sack 1995). In this volume, such an understanding is employed in the contribution by Peter Debaere, Ferdi De Ville, Jan Orbie, Bregt Saenen and Joren Verschaeve (Chapter 2), who analyse the evolution of the EU’s membership status in politico-legal terms. Based on a concept specification that includes both legal and political aspects of status, the authors decide to combine legal and factual competences in the operationalisation of participation. Their contribution, and the following, shows why it is important to define the attributes and thus the meaning of ‘status’, and more generally the meaning of all the concepts employed.

While the notion of ‘status’ may sound straightforward, its attributes can vary significantly. For instance, EU status can be defined as de jure or de facto. In the first case, status relates to the EU’s strictly legal position with(in) an IO. Such a definition would refer to the formal rules and competences. In the second case, status relates to the EU’s factual position with(in) an IO. Defined this way, status would refer to the actual options for action with(in) an IO, which can differ significantly despite the same legal position (Frid 1995: 170). Another aspect is whether the status defines the role of the EU within the corresponding IOs, or its role with the corresponding IOs (i.e. whether it is related to membership or to collaboration).

In the end, the specification of the concept depends on the researcher’s theoretical interest. It can, for example, be argued that if the researcher is primarily interested in the EU’s long-term participation, a concept specification relating to the EU’s legal position may be problematic because the researcher may miss exactly the developments that s/he is interested in – this is the line taken by the authors in this volume. In some cases, EU participation started on an informal basis and was only formalised and based on official rules later on. Hence, scholars may miss cases in which the EU was a de facto observer before it became a de jure observer. For example, in 2012 the EU became an official observer to one of the oldest existing IOs, the Universal Postal Union, following the adoption of the Universal Postal Union Doha Congress Resolution C78/2012. At first sight, this relationship does not seem to be relevant for a scholar who is interested in long-term engagement. However, already in 2004, the European Commission mentioned that it had ‘de facto observer status’ at the UPU (European Commission 2004: 3). In 2012, the Council summarised that the EU ‘has had long-standing relations with the Universal Postal Union and traditionally participated at its work as de facto observer’ (Council of the European Union 2012: 6). Similarly, in the case of the Organisation on International Carriage by Rail (OTIF), the EU was granted membership status in 2011. Again, this seems to be a case that is less relevant when the focus is on the long-term perspective based on a strictly legal definition, because the granting of membership was the EU’s first formal position within OTIF. However, the EU was an informal observer (Grabitz 1975: 56) before it joined the IO as a member (OTIF does not have permanent observers). These examples show why concept specification is central, and why the concepts should always be specified with the particular research interest in mind.

In the end, the most widely shared understanding of participation that is therefore adopted in most chapters of this volume is one based on both legal and factual elements. Most authors indeed look at how the EU participates in IOs in terms of formal rules and in practice. However, they do it in different, nuanced ways. Peter Nedergaard and Mads Dagnis Jensen (Chapter 3) focus on the EU’s coordination and representation at the United Nations (UN) General Assembly and the permanent EU representation at the UN. Coordination also plays an important role in Robert Kissack’s chapter (Chapter 4) on the International Labour Organization (ILO). While initially part of a downloading process, in which the Commission strove for a coordinated ratification of certain ILO standards, coordination among EU member states became part of attempts to upload EU policies into ILO standards from the late 1970s onwards. This development was accompanied by Commission representation of the European Community’s international legal personality in relation to the ILO. That coordination does not have to be formal or institutionalised becomes clear in the chapter by Eleni Xiarchogiannopoulou and Dimitris Tsarouhas (Chapter 6). In addition to EU-internal coordination, which remains informal, the authors also consider the formal and institutionalised opportunities of EU–ILO interaction despite the lack of EU membership. But even interaction between EU officials and their counterparts from an IO does not have to be formal in order to be understood as participation, as Nina Græger shows (Chapter 8). She studies participation as cooperation in the example of the EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Since formal cooperation, however, has been paralysed since 2005, the author draws our attention to the dynamic, informal, ad hoc practices that have emerged over the years. When EU membership in an IO is given, as in the World Trade Organization, it may be particularly interesting to look at participation in terms of the politics at different levels, as the chapter by Amandine Crespy illustrates (Chapter 5). In her study of service liberalisation, the author not only looks at the European Commission as the main protagonist of EU trade policy but also at the role of various interest groups. Moreover, participation can also mean contribution of information, financial and other resources to an IO or the joint coordination of projects, as the chapter by Beth Simmons and Ashley DiSilvestro shows (Chapter 7).

While operationalising the concept of participation, scholars have to specify how they connect it to empirically observable facts (Westle 2009: 177) and measure it. In the existing literature on the EU’s legal status within IOs, it is common to distinguish several positions that the EU can have based on formal rights that the EU enjoys: full membership, full participant, observer and ‘no formal position’ (see Wouters et al. 2008 and also Chapter 2). The EU’s rights are most comprehensive when it is a full member in an IO. While it is difficult to get exact numbers, compilations by scholars and the EU itself show that this is not an exceptional phenomenon at all (Emerson et al. 2011, European Commission 2011). In any case, just as for concept definition, operationalisation implies a certain degree of subjectivity and depends on the researchers’ objectives. As a result, the definition of participation and its operationalisation can vary, even in the same issue area, from one author to another. For instance, while the EU refers to its status in UNESCO and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) simply as ‘observer’ (internal list obtained from the European External Action Service in 2012), Jørgensen and Wessel refer to the EU as an ‘extensive observer’ in these organisations (2011: 270–71). This assessment, however, is not shared by Emerson et al., who also speak of the EU simply as an ‘observer’, and in the case of the ICAO even as ‘subject to invitation’ (Emerson et al. 2011: 118). Since the two academic publications are from the same year, this difference cannot be attributed to a change in the relationship between the EU and the IO. Rather, it is explained by the legal definition of participation chosen by Emerson et al. and their interest in classical diplomacy, while Jørgensen and Wessel focus on politics and are interested in informal practices.

Why and How is the EU Participating in IOs on a Long-term Basis: An Outcome-centric Research Design

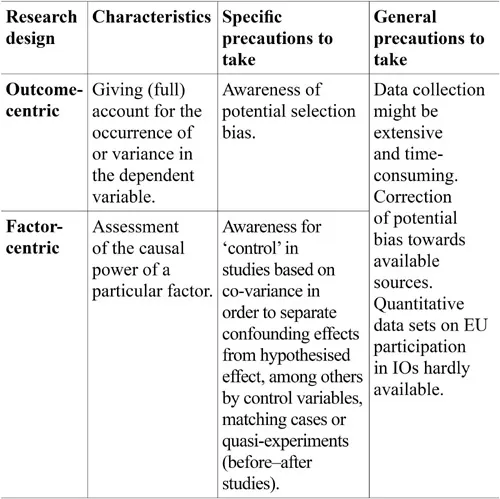

The questions of why and how the EU is engaged in and with IOs on a long-term basis are central for our understanding of the EU as an international actor. At the same time, it is of more general significance for the study of an old problem in European and international studies research – the question of why there is (stable) cooperation? (For a review, see Dai and Snidal 2010.) Given the nature of these questions, which ask for the explanation and specification of a certain phenomenon (‘particular forms of’ the EU’s long-term participation), it is appropriate to opt for an outcome-centric research design, as opposed to a factor-centric design (Gschwend and Schimmelfennig 2007: 7–10; see next section for a discussion on factor-centric design and Table 1.1 (below) for the main characteristics of both approaches). An outcome-centric research design aims at explaining (variance in) a dependent variable. In order to do so, the researcher includes a range of different independent variables in the research design. Eventually s/he collects as many factors as possible that would explain the type of outcome studied. As Gschwend and Schimmelfennig summarise, the goal of an outcome-centric research design is ‘to comprehensively assess potential and alternative explanations by considering many independent variables, Xi, that in toto try to account for variance in the dependent variable, Y, as completely as possible’ (2007: 8). In the case of this volume, this means collecting factors that explain why the EU participates over the long term and on how it does so. This part singles out two challenges that researchers have to tackle when dealing with outcome-centric research design: data collection and selection bias. While the former also applies to factor-centric designs, outcome-centric designs often rely on in-depth knowledge of the subject that is studied.

Table 1.1 Main characteristics of the proposed research designs

Once the dependent variable (in this case participation) is specified and operationalised, the question emerges of how to collect the relevant data. When studying long-term participation, researchers often have to go back in time and look for early data, e.g. when the cooperation started or when certain rights were granted. This is certainly easiest in cases of legal full membership, because acquiring such a status in an IO follows formal procedures based on written documents. Membership of the EU in an IO may come about in two different ways: either the EU accedes to an existing organisation, or it takes part in the conclusion of an international treaty that establishes some kind of organisational structure among the parties (Govaere et al. 2004: 156). In any case, gaining membership status is subject to treaty-making. The EU would have to ratify an accession treaty or the new convention (Hoffmeister 2007: 59) or the constitutive treaty of an IO (Dutzler 2002: 157). This implies that the data collection in the case of full membership is relatively easy. One has to be careful, however, not to overlook early EU membership, for example in the Commodity Agreements, which are renewed at different intervals. Also, the operationalisation should be clear about which dates are taken into account: date of signature, date of ratification, or date of entry into force. There can be considerable time spans between these different steps.

Data collection may be more complicated with regard to observer status or cooperation. The problem is that in some instances either the data simply does not exist or it is difficult to reconstruct. Ideally, a document such as a Memorandum of Understanding/Cooperation, Exchange of Letters, Agreement of Cooperation or a resolution exists. For instance, in the above-mentioned case of the EU’s informal observer status in the OTIF, the European Communities and the OTIF’s predecessor organisation had already exchanged letters in 1959. A good overview on such early documents is given in a compilation by the European Commission (European Commission 1980).

Thus, even in cases where the date is known when official legal observer status or membership was granted, further research may be needed to find out about a potential informal observer status that may have occurred before that date. Also, there may be particular arra...