eBook - ePub

The Evidence Enigma

Correctional Boot Camps and Other Failures in Evidence-Based Policymaking

- 226 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Evidence Enigma

Correctional Boot Camps and Other Failures in Evidence-Based Policymaking

About this book

Why do policymakers sometimes adopt policies that are not supported by evidence? How can scholars and practitioners encourage policymakers to listen to research? This book explores these questions, presenting a fascinating case study of a policy that did not work, yet spread rapidly to almost every state in the United States: the policy of correctional boot camps. Examining the claims on which the implementation of the policy were based, including the assertions that such boot camps would reduce reoffending, save public money and ease overcrowding - none of which proved to be universally accurate - The Evidence Enigma also investigates the political, economic, cultural, and other factors which encouraged the spread of this policy. Both qualitative and quantitative methods are used to test hypotheses, as the author draws rich comparisons with other policies, including Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE), abstinence-only sex education programs, and the electronic monitoring or tagging of offenders in England and Wales. Presenting important lessons for guarding against the proliferation of policies that don't work in future, this ground-breaking and accessible book will be of interest to those working in the fields of criminology, sociology and social and public policy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Evidence Enigma by Tiffany Bergin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

“Evidence-based policy” is a familiar slogan. The phrase, which refers to a public policy that is informed by empirical evidence, came into vogue in the 1990s. It is now widely used by academics, policymakers, and practitioners in the United States, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere (Banks, 2009; Marston and Watts, 2003). Numerous scholars have encouraged policymakers and practitioners to adopt evidence-based policies and programs (e.g., Argyrous, 2009; Davies, Nutley, and Smith, 2000; Dickson and Flynn, 2008; Law and MacDermid, 2008). Yet few scholars have explored the fundamental question of why policymakers sometimes adopt policies that are not supported by evidence (see Bogenschneider and Corbett, 2010, for one exception).

This book endeavors to fill this gap and unravel the political, economic, social, cultural, and other concerns that can trump research evidence in policymakers’ decisions. The lessons of one particular case study—a criminal justice policy that was not supported by evidence but spread to almost every US state during the 1980s and 1990s—are explored in great depth. Although the case study concerns a criminal justice policy, many of the case study’s lessons apply to other kinds of public policies as well, and additional examples are cited to illustrate these applications.

The case study that is discussed in most depth involves correctional boot camps in the US. Correctional boot camps are correctional facilities inspired by military boot camps and typically reserved for younger offenders, who endure a tough regime of military-inspired drills, physical exertion, and rigid discipline (Wilson, MacKenzie, and Mitchell, 2003). Programs generally last for less than a year and require prisoners to wear uniforms and address correctional officers with military-style deference (Gowdy, 1996).

The Dramatic Spread and Contraction of Boot Camps

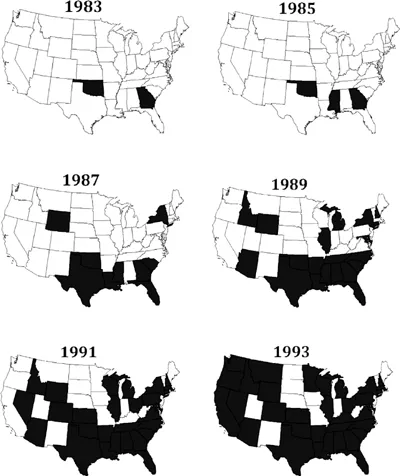

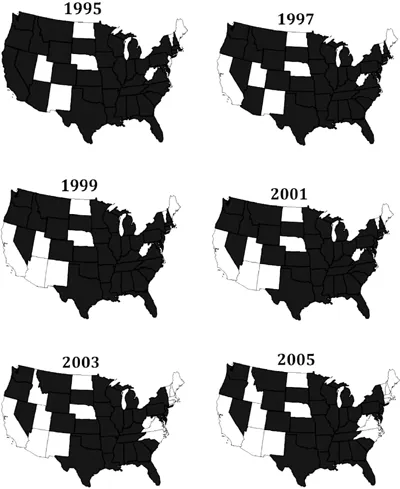

Although similar programs have been trialed in other countries (Atkinson, 1995; Farrington et al., 2002), boot camps achieved their greatest popularity in the US, where a majority of states adopted some form of correctional boot camp in the 1980s through early 1990s. Such programs first emerged in Georgia and Oklahoma in 1983 (Armstrong, 2004). By the end of 1988, 13 US states had adopted correctional boot camp programs for adults (Cronin, 1994; US General Accounting Office [GAO], 1988). By the end of 1992, less than a decade after they first appeared, 32 states had adopted boot camps for adult offenders and 7 states had adopted boot camps for juvenile offenders (Cronin, 1994; Koch Institute, 2000; US GAO, 1993). In the late 1990s and the 2000s, however, the tide turned against boot camps (Stinchcomb and Terry, 2001), and a dozen states had abolished their adult or juvenile boot camp programs by the end of 2005 (Clines, 1999; Coppolo and Nelson, 2005; Salzer, 2008; Schwartz, 1996; Sexton, 2006). Figure 1.1 illustrates the spread and contraction of boot camps between 1983 and 2005, the time period considered in this research project. Shaded states had adopted boot camps for adult or juvenile offenders by the end of the relevant year. States without color had not adopted or had already abolished all of their boot camps. In these maps one can observe the dramatic spread of boot camp programs until around 1997, when more states become colorless again.

Figure 1.1 The diffusion and contraction of correctional boot camps across mainland US states

In the 1980s and early 1990s, American advocates of correctional boot camps claimed that these programs would deliver three important benefits: reduced recidivism (or re-offending); reduced prison crowding; and reduced costs (Burns, 1996; Stinchcomb and Terry, 2001). Yet many studies showed that many boot camps failed to achieve any of these goals (Peters, Thomas, and Zamberlan, 1997; US GAO, 1993). So what other political, economic, and social factors were responsible for the spread of boot camps? What can the spread of boot camps reveal about the factors—other than evidence—that can influence the adoption and diffusion of policies?

Challenges and Contributions of this Research

Although many criminologists have speculated about why boot camps spread and contracted so dramatically (Armstrong, 2004; Cullen, Blevins, Trager, and Gendreau, 2005; MacKenzie, 2010), scant empirical research has examined this issue (see Williams, 2003, for one exception). The lack of previous research could be due to the mammoth theoretical and methodological challenges posed by this issue. How does one conceptualize the spread of policies? How can the numerous twists in policymaking processes and the myriad of concerns that affect policymakers’ decisions be accurately probed? Relatively little previous research has been conducted on criminal justice policymaking, relative to other topics in criminology (Ismaili, 2006). Thus, when this project was begun, few templates existed for modeling the spread of boot camps and policymakers’ decisions about these programs. Methodologically, any quantitative model of the spread of boot camps would need to take into account changes across time and space; standard statistical techniques such as linear or logistic regression would not be appropriate. A qualitative study would be limited by the sheer scope of this phenomenon, as a majority of the 50 US states adopted some form of boot camps.

Quantitative and qualitative challenges were surmounted in this project through a mixed-method approach. A statistical technique adopted from the medical literature, event history analysis, was employed to model the spread and contraction of boot camps throughout the US, as this technique can accommodate large time-series datasets (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones, 2004). Bivariate correlations and cross-sectional logistic regressions were also used to confirm and enrich the event history results. These quantitative findings were augmented by qualitative case studies of two states, selected via a most-similar case selection process (George and Bennett, 2004). Thousands of documents about these states’ boot camp-related decisions were then analyzed through narrative coding (Altheide, 1996).

The use of both quantitative and qualitative methods in this project allowed a comprehensive but nuanced portrait of states’ choices about boot camps to be created. Although the quantitative component was limited by the difficulty of quantifying socio-political constructs such as political ideology and electoral competition, the qualitative component offered an opportunity to explore the potential effects of these constructs in more detail. Similarly, although the qualitative component was limited by its narrow focus on just two states, the quantitative component provided a broader, comparative analysis of all 50 states. The project thus followed Tarrow’s (1995) recommendation to use mixed methods to examine policymaking in order to minimize a study’s limitations and enrich its findings (p. 471).

Choices about quantitative predictor variables and qualitative coding strategies were driven by three key theoretical frameworks: Kingdon’s (2003) influential theory of political agenda-setting (Krehbiel, 1998), Windlesham’s (1998) theory of populist criminal justice policymaking, and the policy diffusion research tradition (Karch, 2007; Mintrom, 1997). Three different theoretical frameworks were employed because the spread and contraction of boot camps were complex processes with multiple constituent parts. Since the frameworks were meant to address these different parts, following the approach of Crosson (1991), the frameworks should be seen as complementary theories rather than competing paradigms.

This project offered an opportunity to empirically test—often for the first time—specific explanations scholars have advanced about the spread of boot camps. Such explanations included MacKenzie’s (2010) suggestion that some policymakers who were military veterans supported correctional boot camps because of their own positive experiences in military boot camps. At the same time, the project also presented a chance to explore the wider role of evidence in policy decisions. In Chapter 2 additional case studies of policies that spread in the US or the UK despite disappointing evaluations of their effectiveness are discussed. These case studies illustrate that the gap between evidence and policy is a fundamental issue that is relevant to multiple countries and policy areas.

Finally, in addition to contributing to the literature on evidence-based policymaking, this project’s results also advance knowledge about criminal justice policymaking and diffusion. For despite recent work by Jones and Newburn (2002; 2005; 2007), Grattet, Jenness, and Curry (1998), Wemmers (2005), and others, both of these topics remain vastly under-researched (Ismaili, 2006; Klinger, 2003). Relatively little is known about the factors that affect policymakers’ decisions about criminal justice policies. This lack of previous research is surprising given that numerous criminologists have expressed interest in working with policymakers and influencing the criminal justice policymaking process (Lab, 2004; MacKenzie, 2010; Wellford, 2010). By quantitatively testing and qualitatively examining different explanations for the spread of boot camps, this project therefore also increases current limited knowledge about criminal justice policymaking, the impact of research evidence on policy decisions, and the factors that facilitate the adoption and abolition of criminal justice policies (Ismaili, 2006; Jones and Newburn, 2007). The project also makes a significant contribution to the policymaking literature because it is one of the only studies to examine both the diffusion and the contraction of the same policy (for another example, see Mooney and Lee, 2000).

An Outline of this Book

Chapter 2 defines the phrase “evidence-based policy” and outlines relevant research on the adoption and implementation of evidence-based policies in criminal justice and other policy areas. Three additional American and British case studies are also presented in this chapter, to illustrate that boot camps are not the only policy that has spread despite research support. Chapter 3 describes what correctional boot camps are, and discusses how policymakers reacted to research evidence about boot camps. Chapter 4 offers an overview of key theoretical frameworks that can be used to conceptualize the spread and contraction of policies such as boot camps. In Chapter 5, the project’s quantitative methods and results about the diffusion and contraction of boot camps are presented. The qualitative methods and results are discussed in Chapter 6. Chapter 7 integrates and compares the findings of the quantitative and qualitative components, proposes several valuable directions for future research in this area, and presents concluding thoughts. Finally, the Appendix presents an overview of each state’s experiences with correctional boot camps and offers information about the sources used to compile data on whether and when states adopted or abolished boot camps.

Chapter 2

Evidence-Based Policymaking

Search the internet for “evidence-based policy” and you will find more than 18 million hits, including a wide range of recent academic, governmental, and popular publications. Yet few of the works explicitly define what they mean by “evidence-based policy” or “evidence-based policymaking” (Sanderson, 2002). For this research project, evidence-based policymaking was defined as “a process that transparently uses rigorous and tested evidence in the design, implementation and refinement of policy to meet designated policy objectives” (Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2010, p. 3). Evidence-based policymaking involves facilitating the “transparent and balanced use of evidence in public policy making” (Cookson, 2005, p. 118). Although similar definitions have been widely employed by scholars and practitioners (e.g., Chalmers, 2003; Strydom et al., 2010), debates persist about the kinds of “evidence” that should influence policymaking (e.g., Davies et al., 2000; Wood, Ferlie, and Fitzgerald, 1998). These and other fundamental controversies are explored in more detail later in this chapter.

History and Recent Developments

The idea that research should guide governments’ policy choices has a surprisingly long history. According to Bulmer (1982, p. 2), perhaps the earliest definitive example of evidence-based policymaking was the Royal Commission on the Poor Law’s recommendations about social welfare reform in Britain. Proposed in 1834, these recommendations were based upon “facts” collected from practitioners—although contemporary scholars have questioned the methodological rigor of this collection process (e.g., Fraser, 2003). In the late nineteenth century, British reformers such as Seebohm Rowntree continued this tradition of approaching social problems through an evidence-based lens (Briggs, 1961). In the US, increased interest in policy analysis in the 1950s and 1960s paved the way for more rigorous evidence-based policymaking (Head, 2010; Lerner and Lasswell, 1951). Indeed, social scientists such as Donald T. Campbell (1969) believed that the Great Society social reforms offered numerous opportunities for evaluating the effectiveness of social programs (Pawson, 2006).

The 1990s heralded a new heyday for evidence-based policymaking, as interest in the “what works” literature increased dramatically in both the US and the UK (as well as in other countries). In particular, the Labour government that took power in the UK in 1997 expressed a notable enthusiasm for this concept (Wells, 2007). This enthusiasm has persisted into the twenty-first century on both sides of the Atlantic, demonstrated by the continuing influence of the UK-based Centre for Evidence-Based Policy (Economic and Social Research Council, 2011) and the US-based Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy (2011). Indeed, a recent report by the think tank the Brookings Institution proclaimed that “the Obama administration has created the most expansive opportunity for rigorous evidence to influence social policy in the history of the US government” (Haskins and Baron, 2011, p. 28). At the same time, research into evidence-based policymaking has greatly increased, and a range of landmark relevant books and reports have been released in recent years (e.g., Argyrous, 2009; Bogenschneider and Corbett, 2010; Head, 2010).

This contemporary drive for evidence-based social policies was partly inspired by the evidence-based medicine movement which also flourished in the 1990s. This movement, as Davidoff and colleagues (1995) have chronicled, promoted the reliance on rigorous scientific evidence in medical decision-making. To this end, in 1993, the influential Cochrane Collaboration (2011) was established to increase awareness of “what works” strategies in medicine, a mission achieved primarily by encouraging the creation and dissemination of systematic reviews—or comprehensive, reproducible reviews of multiple empirical studies that have evaluated the same medical programs or therapies.

The Campbell Collaboration (2011) was founded in 2000 to carry out similar functions within the education, crime and justice, and social welfare fields. In addition to systematic reviews, the Campbell Collaboration also encourages the production of meta-analyses, or statistical analyses that combine the results of multiple similar studies (Egger, Davey Smith, and Philips, 1997). The Campbell Collaboration’s large collection of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of criminal justice programs illustrates that evidence-based practice is not a minority interest within criminology (the field most relevant to this book). Indeed, interest in evidence-based practice within criminology has continued to grow since the 1997 publication of Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising a report by Lawrence W. Sherman and colleagues that was produced under the auspices of the National Institute of Justice. Numerous works have followed in its wake, and interest in evidence-based policy within criminal justice remains high (see, e.g., Taxman and Belenko, 2011; Wellford, 2010). Despite this interest, however, surprisingly little is known about why evidence sometimes fails to influence criminal justice policymaking (Ismaili, 2006)—and it is this question that is at the heart of this book.

Complexities, Problems, and Critiques

Despite this growing enthusiasm for evidence-based policymaking, critiques have been leveled at aspects of the movement. For example, Pawson (2006) has argued that meta-analysis—the statistical technique described above that is a staple of the evidence-based movement—has serious limitations, including the inability to parse the nuances of individual evaluations. Morrison (2001) has similarly asserted that randomized controlled trials, the kinds of evaluations that are often favored by evidence-based scholars, are too reductionist and do not capture the full range of causal mechanisms that affect social processes.

In addition to these methodological critiques, other more fundamental criticisms have also been leveled at evidence-based policymaking. Saarni and Gylling (2004, p. 171), for example, have cautioned that evidence-based policymaking could become “politics disguised as science” as policymakers exploit scientific-sounding rhetoric to achieve their political goals. The potential for the media to misreport or overstate the findings of quantitative studies is much-discussed (e.g., Bushman and Anderson, 2001; Feigenson and Bailis, 2001; Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2006) and enthusiasm for evidence-based policymaking introduces the additional risk that scholars and practitioners could exploit scientific-sounding rhetoric to promote ineffective policies that serve their own interests.

On a more practical level, Perri (2002) has observed that although many policymakers now endorse the rhetoric of evidence-based policymaking, they often have little patience for weeding through the nuances of empirical evidence—and thus make ill-advised policy choices. Gorard (2002) has similarly warned against ignoring the nuances of evidence and overstating the conclusions of evaluations. Finally, Marston and Watts (2003, p. 158) have advanced a more fundamental critique of evidence-based policymaking, arguing that it typically privileges those with elite methodological knowledge and undervalues the contributions of those who lack such knowledge.

In addition to these critiques, several key debates persist among advocates of evidence-based policymaking. Perhaps the most contentious concern the definition of evi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Evidence-Based Policymaking

- 3 Correctional Boot Camps in the United States

- 4 Research Evidence and the Diffusion of Public Policies

- 5 Quantitative Models of the Diffusion and Contraction of Boot Camps

- 6 Case Studies of Two States

- 7 Further Analysis and Future Implications

- Appendix: States’ Experiences with Correctional Boot Camps

- Bibliography

- Index