eBook - ePub

Possession, Power and the New Age

Ambiguities of Authority in Neoliberal Societies

- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides a new sociological account of contemporary religious phenomena such as channelling, holistic healing, meditation and divination, which are usually classed as part of a New Age Movement. Drawing on his extensive ethnography carried out in the UK, alongside comparative studies in America and Europe, Matthew Wood criticises the view that such phenomena represent spirituality in which self-authority is paramount. Instead, he emphasises the role of social authority and the centrality of spirit possession, linking these to participants' class positions and experiences of secularisation. Informed by sociological and anthropological approaches to social power and practice, especially the work of Pierre Bourdieu and Michel Foucault, Wood's study explores what he calls the nonformative regions of the religious field, and charts similarities and differences with pagan, spiritualist and Theosophical traditions.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Approaching New Age

A cameo

‘Fire!’ shouted the woman opposite me. ‘Red!’ I shouted back. I was not ignoring an announcement of impending incendiary catastrophe, however, but playing a game with her. We were sat facing each other in a bare hall in a small town in Nottinghamshire, a county in the English East Midlands, in 1993. Like the other fifty people in the room, we had been instructed to find a person we did not know, sit opposite them, and say, in turn, whatever word came into our heads, trying each time to speak louder than our partner. I had felt self-conscious, especially as my partner, a woman who looked to be in her late thirties or early forties, insisted I go first. There was not much noise in the room – it seemed as if most people were having as much trouble as I in thinking of a word. Afterwards, in the evening as I wrote up my fieldnotes at home, I remember cringing when I recalled my first word, which was simply what I saw when I looked over my partner’s shoulder. It hardly seemed fitting as a word that ‘higher realms’ would have placed into my mind, as Sheila Patterson, the leader of the event, had said would happen. ‘Window’, I spoke, not daring to say it louder. My partner looked quizzically at me and then smirked. I knew she was having as much trouble in speaking as me. After a few seconds, during which time – I admit – I stared at her, as if challenging her word to be more attuned to the theme of the day than mine, she said, in a voice not much louder than mine, ‘Landscape’. I reflected a moment. Her word seemed to be more spiritual, connecting with nature, and was also something that might be seen out of a window. ‘Groove’, I said, raising my voice a little. I was surprised at this and so, seemingly, was my partner, because she immediately laughed. Perhaps she was thinking of ‘groovy’, a word inextricably associated with hippies and the 1960s, the decade in which she, and many others in the room, would have spent her childhood. Born in 1970 I had missed that, spending much of my childhood instead in the Thatcherite world of yuppies. When writing up my fieldnotes, I could not remember many of the words that came next, but I know they came thick and fast, our voices becoming noisier until we were shouting them, challenging each other to say them faster and louder.

The whole room now seemed to be a hubbub of noise and we had to shout to make ourselves heard. I noticed Sheila moving around the room, her eyes level and a knowing smile on her lips. Sometimes, she would bend down to interrupt a couple and talk to them. Although she did not do this to me and my partner, others I spoke to later said she was asking them what their last word had been, and commenting upon what they might mean. She also encouraged people not to be inhibited and seemed to delight in the most vociferous couples. Although this game continued for less than five minutes, it seemed much longer and by the end Sheila was clapping her hands, calling for us to stop. We all seemed to be having fun, though, and wanted to carry on – some couples were talking animatedly about their words and others were laughing hard. It took Sheila several minutes to restore order, but eventually we were all quiet, facing the front where she stood. She then proceeded to ask people to tell us what they had discovered in this game. Some expressed surprise at the words they had spoken and tried to explain these in terms of deeper meanings to their lives. One man, for instance, explained how, quite unexpectedly, the word ‘roof’ had come into his mind, which he interpreted as referring to the limit that for years he had placed on his ‘spiritual’ abilities by not developing them. Sheila responded that it also referred to the limit that people impose upon their ‘ascension’, out of fear for accepting their higher powers and responsibilities. The man nodded and murmured agreement. I did not speak, but my partner told the room that she had uttered the word ‘fire’ and felt a ‘deep glowing’ within her. She believed, she said, this was because she had had a lot of energy in recent weeks, feeling ‘on fire’ and ‘focused’. Sheila explained that the ‘Ascended Masters’ could set fire to our old ways of living, releasing us to do what we really wanted.

This game took place in a day’s event in which Sheila, an Australian in her forties, told us about her experiences with the Ascended Masters, highly evolved beings who manage the evolution of humanity by controlling the universe’s energies. Describing herself as a ‘channeller’, Sheila was able to communicate the Masters’ discourses, as they spoke or wrote through her. More than that, however, she was able to interact with them personally and to travel throughout space and time to perform tasks they set her. Our evolution, she explained in several talks during the course of the day, involves our eventual ‘ascension’, whereby we will move to a ‘higher vibration’ or ‘dimension’ and leave the ‘physical plane’. The word game and the others we played during the day were exercises, she said, to help ‘open’ ourselves to the Masters and make it easier for us to ascend. Despite the jocular tone of the day, there was much seriousness too, with opportunities for Sheila’s audience to question her about changes in their own lives and the relevance of the Masters to those. Sheila was touring Europe and America, and although it was possible to sign up for a monthly newsletter she produced about her communications from the Masters, there was no group or society, with which she was associated, to join, even informally. Julie and Andrew Spencer, who hosted a fortnightly meditation group that I had recently begun to attend, had organized this event. The Spencers organized day events for other channellers too, but had no formal attachments to any, although they frequently articulated their views.

I start with this cameo because scholars see channelling as typically, sometimes archetypically, New Age. Many scholars would also view the sort of meditation group I researched, its attenders and their activities as part of the New Age, which they see as a diverse collection of practices, beliefs and ideologies that has arisen in recent decades principally in Euro-America.1 This diversity is seen, however, as bearing a strong common theme that leads most scholars to speak of the New Age as a movement: the primacy of self-authority. The New Age is seen as a religion – or, more usually, a spirituality – in which people choose what to do, and how to do it, on the basis of their own authority, rather than being directed by authorities external to them. External authorities and traditions are utilized, through marketplace consumption, merely as resources from which the self draws. Scholars see this situation as reflected in the discourse of the New Age, which extols the self, its fulfilment and expression, such that these authorities act to encourage and facilitate people’s expressions of their own authority. In fact, in recent years, scholars have viewed the New Age as designating a monumental shift away from traditional religions, in which external authorities muffle the self, and towards self-authoritative spirituality.

This opening cameo indicates a quite different interpretation. The authority of the channeller, Sheila, is clear enough. Her audience spent a whole day listening to her experiences of working with the Masters, including carrying out important and dangerous duties for them, and the authoritative communications they brought to us through her. In addition, she directed us in exercises designed to enable us to communicate more openly with the Masters, and advised us in how to interpret our life experiences in terms of their ideas and actions. Thus, whilst placing much emphasis upon the requirement for us to look within ourselves for knowledge and confirmation, as in the game in which significant words arose unwittingly into our mouths, Sheila did this specifically by emphasizing the authority of the Masters, their communications and actions on our behalf, and of herself, who carries out their will and works in tandem with them. Her interruptions, interpretations, descriptions, communications and explanations intertwined with our learning of these techniques and discourses of self-exploration and self-expression. Other authorities were also present, such as the Spencers who had invited Sheila, who knew many in the audience well, and who often spoke about her (and other channellers’) ideas at the meditation group.

These authorities cannot be brushed aside as mere resources, between which each individual picks and chooses without surrendering an essential self-authority, or through which they learn the ability to value and express such self-authority. They strongly affected people’s experiences during the day, remaining afterwards as ways they thought about themselves and their lives, not only in terms of the ideas or beliefs they had heard, but also in terms of ethos and emotions. In the following months and years, I had much opportunity to see how people had been affected by this event as well as by other channelling events, by group participation in activities such as the meditation, and by being taught techniques such as those for healing and divination. In sum, the people I researched were affected by numerous authorities, their lives becoming entwined with these in complex and subtle ways. The idea of separating their self-authority from these authorities, of seeing the former taking primacy over the latter, seems as false as viewing these people as moulded by such authorities as if they were inert lumps of clay.

This book is a refutation of the scholarly discourse about the New Age and self-authority, but also a consideration of how social phenomena classified under this label should be understood. It attempts to grasp more realistically the manner in which authorities are enfolded into the self, that is, into the ways in which people are socially subjectified and come to understand themselves. This is a dynamic process that requires a dynamic methodology, one that seeks to situate individuals and groups in the diversity and history of their practices. Focusing upon a number of these in Nottinghamshire over several years, I show that they are characterized by multiple authorities, none of which are formative in shaping them, but all of which contribute in so doing. This proliferation of what I call nonformative authorities has been almost entirely neglected by the sociology of religion.

The Nottinghamshire network

Groups and interconnections

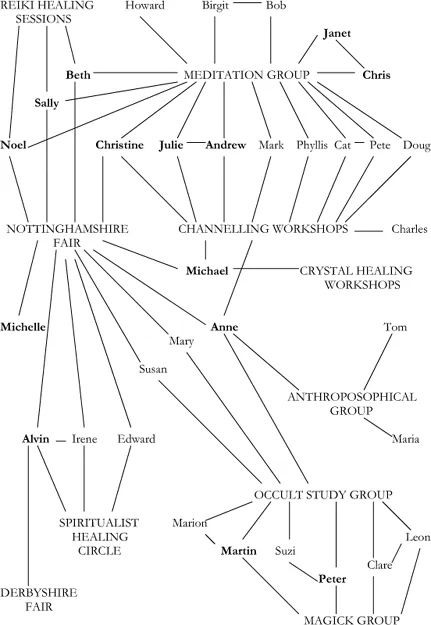

Nottinghamshire is a mixture of small towns and rural villages, dominated until recently by the coal mining industry, and Nottingham, a city with a population of around a quarter of a million people which with its thriving shopping and night scenes acts as a central pull for the rest of the county, as well as for the inhabitants of bordering counties Derbyshire and Lincolnshire. From 1992 to 1994 and again in 1996, I researched ethnographically a number of groups in this county, and occasionally further afield in England, which formed part of what I somewhat arbitrarily designate the ‘Nottinghamshire network’. Figure 1, provides a schematic representation of this network: groups studied, selected participants, key informants, and connections between people and groups. This intention was to conduct an ethnographic study of the New Age in Britain, but I soon began to question my original perspective. Although the religious groups and practices I researched were of the sort described in the scholarly literature as New Age, also falling into descriptions of alternative or non-mainstream religion, the interpretations developed through these perspectives were at significant variance with what I discovered in the field. In this chapter, I sketch my object of study and my theoretical orientations for interpreting the network.2 The structure of the book is also outlined, chapter by chapter.

The social phenomena I studied may be viewed in two ways. The first focus falls on the different groups and events, which may be seen as discrete entities with their own histories, social organizational and authority structures, beliefs and practices. The second focus is on the interconnections between the individuals, groups and events as a whole, since there was a large degree of crossover between them in terms of people, practices and beliefs. Regarding the first focus, the longest period of fieldwork (18 months) was conducted with a meditation group styled around a representation of the teachings of the ancient Jewish sect of the Essenes. This group met fortnightly with around fifteen participants practising a meditation led by one or two of their number, before spending the rest of the evening socializing. Only half the attenders were regularly attending members, the rest coming from a wider pool of interested people. Important informants at the group were two couples in their forties, the Lovells, who directed the meditation and had founded the group, and the Spencers, in whose house it was held, and four younger people: Christine, Sally, Beth and Noel. The Spencers occasionally organized events in which channellers, such as Sheila Patterson, conducted workshops. These attracted around fifty people, including several from the meditation group, although not the Lovells who, like many in the network, were sceptical of channellers. These names, like all others including those for groups, are pseudonyms. Exact quotes from field subjects are placed in quotation marks.

Figure 1 The Nottinghamshire network

This figure shows groups studied with selected participants. Names in bold indicate key informants and lines between individuals indicate marriage or partnership

Before my research began, I had no experience or contact with this group or any others like it. I learnt about the meditation group through Anne, an older retired woman, whilst attending an Anthroposophical group for four months. I had originally identified this group as an easy way into researching the New Age, since scholars linked this to Anthroposophy, and it was simple to identify a local group because they publicly advertised their meetings. Whilst at the meditation group, I also made contact, again through Anne, with an occult study group, which I also spent four months researching. The Anthroposophy group’s fortnightly meetings combined meditation with discussions based upon readings of Rudolf Steiner’s books, which, during my time there, looked at his idea of ‘spiritual science’, in which an understanding of human evolution and being enables an understanding of human potential and development. At least a dozen people attended, with half of these being regular attenders. The occult study group’s fortnightly meetings were based around a talk, followed by discussion and socializing. Topics varied widely: from astrology to the ideas of David Icke, and from the significance of Egyptian pyramids to occult activities in the Third Reich. Practitioners of a wide range of pagan and occult practices and groups attended these meetings, including witches, astrologers and those interested in Aleister Crowley’s teachings. Martin, a man in his thirties who established and ran the group, gave two-thirds of the talks and was interested in most of these different traditions.

This fieldwork took place from winter 1992 to autumn 1994, at which time my research was interrupted due to ill health. I resumed fieldwork for six months in 1996, after being introduced to a friend’s work colleague, Michelle, who had a fascinating biography of religious practice that included many practices common in the groups I had already studied. Michelle knew several of the people I had already researched and told me about a religious fair that had been started about a year earlier. This was held monthly on Sundays in a town centre hotel, attracting around one hundred and fifty people who paid to attend workshops and lectures and to browse the twenty or so stalls that offered services, information and goods. Activities at the fair included spiritualism, healing practices and religious traditions such as Buddhism, and amongst the speakers and stall-holders were Christine, Sally and Noel from the meditation group. Its initiator and organizer, Michael, a friend of Michelle’s, practised crystal healing and had a history of experience involving shamanism, channelling and Reiki (a form of healing by which an initiate acts as a channel for a universal energy force). Alvin, a spiritualist healer, held a stall at the fair and it was through him that I researched a spiritualist healing circle, which he ran with his wife and another man, all of them in their fifties or sixties.

Alongside these often over-lapping periods of fieldwork with groups, research also involved attendance at other events, leading to meetings with people who had only sporadic social connections within the network. As well as the channelling workshops, such events and meetings included fieldwork with Charles, a Londoner in his thirties who had attended one of the channelling workshop the Spencers had organized and with who I attended the London Festival for Mind-Body-Spirit in 1994; participation in Reiki healing sessions with Sally, Noel and Beth; an interview with the manager of a local holistic health centre; attending with Alvin a religious fair in Derbyshire; participation in one of Michael’s crystal healing workshops; and attending various occult and pagan meetings with people from the occult study group.

This focus on groups and events needs to be complemented with a focus on interconnections. This constitutes the second way of understanding the network: not as a static structure of fixed points, but as a dynamic process of interchanges of information and personnel, relying heavily on socializing. As such, the groups and events that may be thought of as fixed points in the network were themselves in flux, being open to the introduction of different and often challenging ideas, practices and people. Whilst some, such as the Anthroposophical group, were more resistant to these because of their more organized nature, others, such as the meditation group, could be significantly transformed, as its history showed. Interviews conducted with key informants consolidated this focus by demonstrating the network of interrelations between groups. An understanding of this crossover requires a perspective that moves beyond a consideration of each group or event as it was in itself and hence the notion of a network is employed.

By referring to my object of study as a network, I am therefore drawing attention to the considerable flows in people, practices and beliefs between a number of different groups and events within a relatively limited geographical area. The intensity and persistence of these flows indicated that what I was investigating could be usefully designated as a network, although this should not imply that those involved referred to the social space of their religious practices in such a manner, for they did not. Indeed, most did not conceptualize this social space at all, despite showing great interest in what was going on across it. Furthermore, the variation in the intensity and persistence of these flows demonstrated that some people and groups were more closely tied together than others and could thus be described as existing towards the core, rather than the periphery, of the network, in terms of clusters of interconnections rather than the delineation of a bounded entity. As well as the groups researched, I learned of a number of other groups and events that could be located in the network, such as an astrology group, a group studying the writings of the occultist Gurdjieff, a group named Hundredth Monkeying!, a cancer care group run by the Spencers, meetings for a small number of young men run by the spiritualist healer Alvin, and a number of other local religious fairs and healing centres.

Methodological considerations

The methodology employed in studying this network is based upon anthropological and sociological traditions of ethnography to pursue a contextualized interpretation. As the more recent history of these traditions has shown, it is essential also to contextualize the researcher within ethnographic practice. As already indicated, my initial contact and subsequent associations in the field had little clear direction, often being the result of arbitrary meetings and acquaintances, so it is important to situate myself in relation to people and events. This reflexive approach provides insight into how my experience of conducting ethnographic research informed my relations in the field and thus my interpretation of what people were doing, how and why they were doing it, and how they understood what they doing. Although I sought to gain an understanding of the world as seen from field subjects’ perspectives, it was important also to maintain a critical stance towards those perspectives so that their location in social conditions could be reflected upon, rather than adopting them as a natural way of looking at the world.

Indeed, this is one of the most problematic features of New Age studies, for they almost invariably adopt what may be described as insiders’ perspectives in place of scholarly understanding based upon a critical interpretation of these. Worse, the insiders’ perspectives that are adopted are generally those of published authors, who, in the context of publishers’ categorizations of a genre named ‘New Age’, typically proclaim themselves to be ‘New Agers’ and to represent a ‘New Age Movement’. In pursuit of a more critical stance, my approach not only problematizes the models constructed by field subjects and the authors they read, but als...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Approaching New Age

- 2 The field of New Age studies

- 3 Power, self and practice

- 4 The meditation group

- 5 Channelling workshops

- 6 The Nottinghamshire fair

- 7 Spiritualism and paganism

- 8 Nonformativeness, possession and class in neoliberal societies

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Possession, Power and the New Age by Matthew Wood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Comparative Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.