![]() PART 1

PART 1

Histories and Reflections of Contemporary Teenage Witchcraft![]()

Chapter 1

The Pagan Explosion: An overview of select census and survey data

James R. Lewis

Because contemporary paganism is a decentralized subculture rather than an organized religion, any effort to construct a general profile of – and, especially, to quantify – participants necessarily involves some degree of speculation. Since the late 1960s, there have been widely varying estimates of the total population of practicing pagans.1 To focus on recent estimates, in a 1999 article Jorgensen and Russell2 present a figure of 200,000 practitioners in the US (though the authors also indicate that ‘estimates of twice that number are not implausible’). This is an important statistical study, which indicates that pagans tend to be successful, educated and involved, rather than the marginal individuals they had been portrayed as in certain early studies. Although published in 1999, the empirical data for the Jorgensen–Russell study was collected in 1996. Other recent scholarly studies also place the pagan population at around 200,000.3

In contrast, figures put forward by other observers and many insiders are much larger. For example, in 1999–2000, then First Officer Kathryn Fuller of the Covenant of the Goddess (COG) – a large networking organization and umbrella group that promotes official recognition of Wicca or Witchcraft as a religion in North America – initiated an Internet poll in response to public attacks on pagans in the military. Based on 32,854 responses (30,735 of whom were Americans, 1,219 Canadians, and 900 Others) Fuller estimated that there were 768,400 Witches and pagans in the United States. This was an extrapolation based on an estimated total return of 4 per cent. This is in the same ball park as a figure mentioned by Bruce Robinson (the primary architect of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance website), who wrote that, if pressured, he would estimate the number of Wiccans in the US as ‘something on the order of 750,000.’4

An important though neglected source of information bearing on the question of numbers of adherents to alternative religions is national census data. In 2001, the censuses of four English-speaking countries – New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom – collected information on religious membership. There was also an important religion survey conducted in the United States in the same year, the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS).5

New Zealand collected religious membership data in two prior censuses, in 1996 and 1991. Australia also collected relevant membership figures in 1996, but not 1991. And Canada collected religion data in 1991 but not 1996. In 1990, the Graduate Center of the City University of New York conducted a National Survey of Religious Identification (NSRI). Eleven years later in 2001, this same center carried out the ARIS survey. Comparing the numbers of self-identified pagans in 2001 with earlier years reveals a startling pattern of explosive growth in all of these countries.

Though a few scholars and observers of paganism have referred to one or more of these censuses,6 no one has yet attempted a general overview. In the current article I will survey this census data and the relevant data from the ARIS survey for the light this data sheds on increasing participation rates in paganism. In the article’s latter sections, I will discuss two of the factors fueling this rapid expansion, the Internet and the phenomenon of adolescent paganism.

Statistics from Canada and the United Kingdom

The 2001 Canadian census recorded 21,085 pagans out of a national population of 28,000,000, or somewhat less than 0.1 per cent of the total (0.075 per cent). The 1996 census did not measure religious affiliation. The 1991 census recorded 5,530 pagans. Canadian pagan scholars with whom I have communicated have said that, based on their own research, these figures are inaccurately low. They speculate that many people were cautious about identifying themselves as pagans, and as a consequence did not report their religious affiliation to census takers. This issue aside, a striking aspect of the data that emerges when the two censuses are juxtaposed is that Canadian paganism experienced almost four-fold growth in a decade. As we will see, Canada has not been the only country to see a remarkable growth in its pagan population.

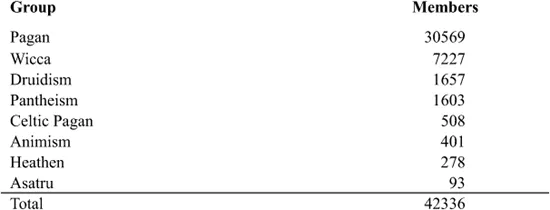

The 2001 United Kingdom census recorded a ‘reasonably good spread’ of different pagan groups, and is the best national census in this regard.7 Regrettably, religious participation was not measured in previous censuses. The figures for the English and Welsh part of the census for pagans are as follows:

Table 1.1 Pagan Statistics for England and Wales from the 2001 British Census

A total of 42,336 pagans represents a bit less than 0.1 per cent of the Welsh and English population of 52,041,916 (0.081 per cent). Although this figure strikes observers of the British pagan scene as too low, it is very close to the percentage derived from the Canadian census.

An important factor influencing the outcome of the religion aspect of the census was that someone decided it would be a fine bit of humor to encourage people to write ‘Jedi Knight’ in the religion category. As a consequence, 390,127 people in England and Wales responded that they belonged to the Jedi Knight religion. Although this is quite amusing, I would speculate that proportionally more of these self-designated Jedis were involved in some form of paganism than the general population, though how much more would be difficult to determine.

Religion survey data for the United States

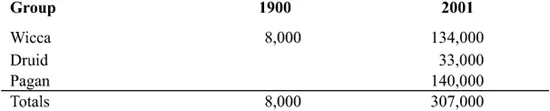

Unfortunately, the US census does not collect religion membership data. However, in 1990 the Graduate Center of the City University of New York conducted a National Survey of Religious Identification (NSRI) via randomly dialed phone numbers (113,723 people were surveyed). Eleven years later in 2001, the Center carried out the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) in the same manner (over 50,000 people responded), though callers probed for more information than the earlier NSRI. Categories were developed post-facto. The results were quite interesting with respect to the pagan population:

Table 1.2 Pagan Data from NSRI and ARIS8 9

Although it would have been much more useful if researchers had broken down their data into more subcategories, their results are nevertheless striking. In a period of eleven years, the pagan population (counting Wiccans, Druids, and pagans together as Pagans) increased more than thirty-eight-fold. And even if we confine our focus to self-identified Wiccans, the jump from 8,000 to 134,000 represents a seventeen-fold increase. When the total pagan population of 307,000 is divided by a US population estimate of 207,980,000, we get a participation rate of 0.145 per cent – or about twice that of Canada.

New Zealand national census data

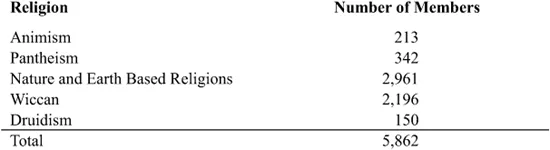

The New Zealand national census of 2001 broke down paganism into five subcategories. In the prior two censuses the single generic category was simply ‘Nature and Earth Based Religions’:

Table 1.3 Alternative Religion Statistics from the 2001 New Zealand Census10 11

The 2001 total of 5,862 self-identified pagans represents 0.157 per cent of the 3,737,277 people who responded to the 2001 census. Based on these statistics, the ‘participation rate’ for New Zealand pagans is about twice what it is for the UK, and slightly more than that of the US.

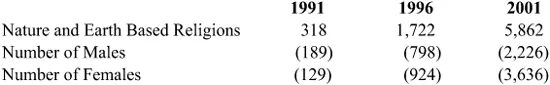

Because New Zealand was the only country to gather New Religion membership data during the last three five-year censuses, it contains some of the most interesting data for assessing long-range trends. In the table below, I have also included participation by sex because of how it reflects a change from a predominance of males to a predominance of females in ‘Kiwi paganisms’:

Table 1.4 Growth in Paganism from 1999 to 2001 in New Zealand (by Sex)12

These figures indicate a greater than eighteen-fold expansion of paganism in the ten-year period from 1991 to 2001. From 1996 to 2001 paganism experienced a threefold expansion. It should be interesting to see the results from the 2006 census.

Australia national census data

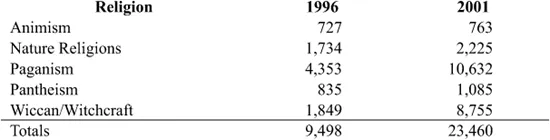

The Australian census contains information similar to the New Zealand census, except no relevant data was gathered in 1991. Conveniently, Australia reported all of the data from 2001 in terms of a straightforward comparison with the 1996 census:

Table 1.5 Pagan Statistics from the 1996–2001 Australian Census

The rise from 9,498 to 23,460 represents slightly less than a 250 per cent increase in five years, a rate of increase comparable to the rate of expansion in New Zealand between 1996 and 2001. With respect to number of total census respondents in 1996 (17,750,000) and 2001 (18,767,000) this represents a rise from 0.051 per cent to 0.125 per cent. The 0.125 per cent rate of participation is less than for New Zealand and the United States, but greater than for Canada and Britain.

The Internet, Llewellyn Publications and paganism

When taken together, the above figures present a compelling overview of a spiritual movement experiencing explosive growth across English-speaking countries. What happened to prompt this remarkable expansion? Two important factors (not to exclude the possibility of others) contributing to this rapid expansion were the Internet and the emergence of adolescent (‘teen Witch’) paganism.

To refer back to the Jorgensen-Russell study mentioned at the beginning of this paper: In 1996 when they were gathering their data, the Internet was just beginning to take off.13 Between 1996 and the present, the internet exploded. Perhaps more than any other religious community, pagans quickly became involved in this medium.14

For my present purpose, one of the most striking aspects of Jorgensen’s and Russell’s research is that they excluded all individuals under eighteen, noting that ‘Neopagan beliefs and practice are popular among American youth, but they usually do not participate in this subculture except when their family of origin is Neopagan.’ This may have been an accurate observation in 1996 when Russell collected the empirical data reported in their article, but it is highly inaccurate with respect to the new crop of pagans, many of whom become involved while in middle school and high school. The growing number of younger participants is reflected in the proportion of teenagers seeking to communicate with other pagans on the Witches’ Voice website, www.witchvox.com, the largest international networking website for pagans and Witches. On 18 March 2002, for example, this website contained personal notices from 35,261 ‘Witches, Wiccans, Pagans and Heathens.’ Out of these, 7,241 – or slightly more than 20 per cent – were teenagers. From a casual perusal of their notices, it is clear that the great majority of these young people are not being raised in pagan households.

I do not think this means that Jorgensen and Russell were mistaken, but rather the demographics of the pagan movement have shifted radically since 1996. One of the most important factors responsible for this shift has been the Internet.

The Internet did more than simply bring new people into the movement; it also dramatically altered the overall social organization of paganism. Never a centralized movement, for well over a decade before the Internet took off in 1996, paganism had been experiencing increasing fragmentation due to the growing numbers of solitaries – individuals who, for the most part, practiced their religion alone, though they might occasionally participate in group rituals, particularly at festivals. The advent of online paganism dramatically accelerated the numbers of pagans practicing their religion by themselves. Not only did the Internet make the solitary option more viable for pre-1996 pagans, but also the great majority of new ‘converts’ brought in via the Internet tended to become solitary online pagans. The Internet allows pagans to participate actively in a lively online community without ever ‘getting together’ in the non-Internet realm. It is also no longer necessary to subscribe to print periodicals to keep up with the movement, and anything one might desire as far as books and supplies can be obtained through online stores (e.g. The Witches’ Voice contains links to over 500 online stores). And it is not just specialty stores and specialty publishers like Llewellyn that have ‘cashed in’ on this phenomenon. Citing a 1999 posting to a Wiccan mailing list that included a personal interview with a Barnes & Noble executive, Bruce Robinson reports that,

A marketing executive from Barnes and Noble, the ‘World’s Largest Bookseller Online,’ estimates a U.S. ‘Pagan Buying Audience’ of 10 million…. Of course, this number is only an estimate of the number of people who buy Pagan books – not the number of actual Pagans. B&N allocates more space to Pagan books than the audience would indicate, because ‘Pagan book buyers’ tend to buy more books per capita than those of all other faith groups.15

The Internet would probably not have had the major impact it did had not certain changes already been taking place within paganism. I have already referred to the increasing numbers of sol...