![]()

Chapter 1

Actors and ways of intervention

This chapter deals with the concept of social change programmes. We discuss some of the background of the theoretical and political issues entailed in attempts to solve lifestyle-related problems. Next, we introduce different actors, such as policy makers, market enterprises and civil society organisations, the main players who launch various interventions into consumers’ and citizens’ lives. After that, we juxtapose competing approaches (mainly individual-based social marketing and behavioural economics, including ‘Nudge’) with practice-change conceptualisation, although a more detailed discussion of the latter takes place in Chapter 2. The aim is to give programme designers a basic map of the field, in terms of concepts and actors, which will help them to position themselves.

1.1 Lifestyles and social change programmes

Alcohol and tobacco abuse, irresponsible driving styles, drugs, unhealthy nutrition, food risks, drowning, fire deaths, non-sustainable energy use, accumulation of waste and personal financial incapability: these are just a few examples of the social problems connected to modern lifestyles. These problems affect all members of society, not only risk groups. Alcohol abuse affects the welfare of a society and is a drain on our tax revenue. It is society as a whole that benefits, directly or indirectly, from attempts to alleviate or solve these problems.

This guidebook focuses on programmes that aim to initiate social change by making population groups think and act differently in order to improve the welfare of these groups and society as a whole. There is no agreed-upon common label either for such programmes or for related policies. Decades ago social scientists used the term life politics (Giddens, 1991; Roos and Hoikkala, 1998). This was defined by the well-known British sociologist Anthony Giddens (1991):

While emancipatory politics is a politics of life chances, life politics is a politics of lifestyle. Life politics is the politics of a reflexively mobilised order – the system of late modernity – which, on an individual and collective level, has radically altered the existential parameters of social activity. It is a politics of self-actualisation in a reflexively ordered environment, where that reflexivity links self and body to systems of global scope … Life politics concerns political issues which flow from processes of self-actualisation in post-traditional contexts, where globalising influences intrude deeply into the reflexive project of the self, and conversely where processes of self-realisation influence global strategies (p. 214).

In our book, we build on that definition, while focusing on policy-making and actual programme design useful in tackling ‘lifestyle problems’. Thus we deal mainly with a set of political, economic, cultural and social tools implemented to shape, directly or indirectly, how people go about their own lives, as well as influencing other lives and social structures.1

These interventions are based on the assumption that, unlike traditional societies, in the contemporary era consumers’ and citizens’ abilities and opportunities to make (informed) choices and to consider the long-term consequences (pertaining to the natural environment, health, the wider social good etc.) of their actions have increased due to various socio-technological developments. Moreover, the lifestyles exercised, adopted and abandoned by the (general) population are believed to be the keys that open the door to further social prosperity. For example, many sustainable and innovative approaches to energy production and consumption struggle with the ‘consumer factor’, so that engineers and life scientists are waiting for answers from social scientists on how to educate the ‘proper consumer’. Jeja-Pekka Roos, referring to Giddens (Roos, n.d.), has defined this as ‘a new moral basis for existence in a situation where people have choices, resources and risks’ and she states that they should develop new ethics concerning the issue of ‘how we should live in a post-traditional order’. Giddens’s ideas are further explored in Chapter 2.

Many classical social theorists and contemporary researchers are very sceptical about this approach and say that it is impossible to talk only about individual choices or decisions, as they are deeply entrenched in social power structures. Explanations are sought regarding how individual agents interrelate with power structures and how social change may occur, not only top-down, but also bottom-up. Social scientists have proposed (in addition to such macro-level categories as class or gender) more nuanced and dynamic concepts, such as habitus (Bourdieu, 1972/1977), life experience (Ricoeur, 1984/1988) and lifeworld (Habermas, 1981/1987), which mediate between social power structures and individual agents. This guidebook provides help in designing more close-to-life programmes aimed at shaping how people arrange and make sense of their lives and social relations in such areas as contested consumption, risk-taking, health-related activities and other everyday habits that affect well-being. Thus we use the term ‘lifestyle’ in a broad sense that includes not only individual activities, but also social relations.

Social scientific debate about the possibilities of designing and regulating lifestyles in late modern societies, however, raises the issue of how much legitimacy the state (and authorities in general) has in the private lives of citizens and consumers. The Finnish sociologist Pekka Sulkunen (2010) has presented a convincing argument about the movement from pastoral (the paternalistic state as a ‘shepherd’) to epistolary power (guidance from a distance involving ‘the ethic of not taking a stand’), resulting in the ‘predicament of prevention’ (p. 141–2). It is unacceptable in late modern Western societies that a state directly issues orders to people on how to live. Thus the state can, in most cases, only admonish, and arrange a regulatory framework of rules and laws. The latter involves a complex and extensive process of engagement by interested parties, in which severe conflicts of interest surface.

Thus, in this guidebook we address both theoretical and practical conundrums faced by state organisations, civil society organisations2 and enterprises when they try to regulate and improve (and sometimes police) the whole society’s well-being. In late modern societies, there are limits to what kinds of social change programmes can be undertaken. These limits stem not only from the tight purse-strings of organisations and insufficient human resources, but also from political and moral considerations, as the brief argumentation above illustrates. Programme designers need to be informed about these concepts and debates, knowing that all their steps are political: ‘life political’, to use Giddens’s (1991) term.

However, we are conscious of the sometimes frustrating nature of such debates. They may lead to dismay: what can we do, is there a point in any kind of intervention if the state has no legitimacy to intrude into lifestyles and if individuals alone are too enmeshed in their daily habits, and how can difficult social problems be solved at all? This guidebook does not recommend sitting back and doing nothing but theorising. Programmes informed by social theory, close analysis and participation by various stakeholders are, in our view, ways to deal with problems.

Think and stretch

Recall a recent programme or campaign initiated by (a) public or non-profit organisation(s) that has caused controversy in the media.

What was the programme about?

What did the media debate touch upon, and why was the campaign contentious?

There are several ways to shape – directly or indirectly – the ways people lead their lives:

1. an individual recognises a problem and solves it herself (e.g., a young woman quits smoking after getting pregnant, because she knows that smoking is dangerous not only to herself but also to her baby);

2. a collective solution is found (e.g., support networks for addicts and individuals suffering from eating disorders);

3. a change is brought about by social pressure (e.g., condemnation of public urination);

4. restrictions are imposed on harmful behaviour (e.g., limits on alcohol sales);

5. useful activities are promoted by changing the physical or virtual environment (e.g., increasing the number of reverse vending machines and collection points for waste paper and dangerous waste).

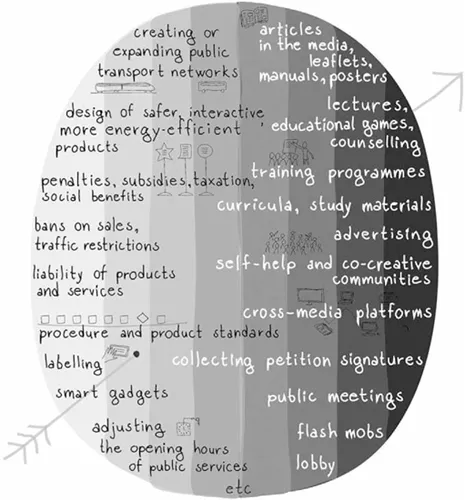

Figure 1.1 Possible tools of intervention to achieve social change

In the process of seeking solutions, we can distinguish between symbols and material stimuli, between manipulation of the body and of the mind, between voluntary and imposed change, and between people’s own initiatives and external institutional intervention. Programme implementers can employ multiple methods and tools, both tangible, such as physical intervention through forming or adjusting the environment and regulations, and intangible, by the use of words, images and sounds (see Figure 1.1).

It is relatively easy to introduce new fads and fashions, but transforming the ways people make sense of and manage their everyday lives is an arduous task, because it involves hundreds of details. The ideal social change programme stimulates processes of self-regulation in social groups or the whole society, cultivating the desired behaviour pattern, which reproduces itself so that target audiences accept the recommended practices and apply them in their everyday routines without the need for constant external pressure. This is usually a long process and cannot be achieved with one programme. For example, in Finland the number of fatal fire casualties decreased after smoke detectors were made compulsory, but started to increase again after two years, because detectors’ batteries started to die (V. Murd, personal communication, October 8, 2009). Therefore, people were reminded that they needed to check and re-charge them. It is possible that battery inspection will become routine and reminders will become unnecessary. Or household appliances could have a device that prevented them from being switched on before smoke detectors had been checked. Different mechanisms of how social change can be initiated are described in the subsequent section.

Think and stretch

Think about the programmes and projects you have been active in during the past two years. What tools shown in Figure 1.1. have you used? Why? Which ones have you not used? Why not?

1.2 Actors in the field

Changes in individual conduct may be achieved by the efforts of different actors: public administrations, governments, business organisations and civic movements, as well as small changes brought about through individual civic or consumption choices. In practice, the actors of different domains use different means of intervention. Their choices depend on their power and resources, but also on general unwritten codes of conduct. Bourdieu (1972/1977) has described these codes as fields which dictate what kind of strategies and rules should be followed to preserve or gain positions of power in the fields. What is appropriate in the public sector is not appropriate for businesses, and what is allowed in business is not acceptable in civic movements. The programme initiator needs to acknowledge the rules of the game (see Bourdieu in Chapter 2, section 2.1); the partners from governmental, business and non-governmental sectors need to follow them. Knowledge of the rules of conduct is just as important as knowledge of the behaviour of the final target group of the programme: in order to change someone’s conduct, the initiator needs to carefully consider his own.

Public authorities are considered the most powerful actors in addressing social change, because they control tax revenues and exercise legislative and executive power. But life politics is also a part of the agenda of other institutions. Although market mechanisms are often seen as producing social risks and problems, business organisations also increasingly participate in solving social problems, as a part of their social responsibility and marketing initiatives. They offer material resources and know-how to the public and non-profit sectors. Non-governmental organisations, social enterprises and local community groups are often closest to target groups and have ample hands-on knowledge in working with the beneficiaries of the programmes. Expressing their opinions may also bring about new policy interventions.

The connection between the initiatives of different actors is dynamic and complex. For example, various seminal works (e.g., Risk Society by the German sociologist Ulrich Beck, 1992) claim that the development of social risks and the bads that are produced as side-effects of economic goods is always a step ahead of policy interventions. The shortcomings of policy become, in turn, the subjects of social debates and movements.

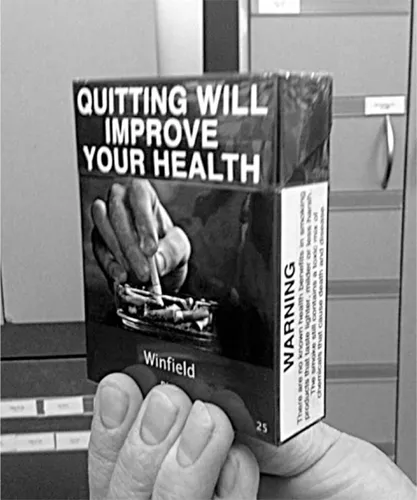

Tobacco policy is most often referred to as an example of how legislative forces are always a step or two behind market development. The social perception of tobacco problems shifted to health quite recently, when scientific organisations joined the coalition against tobacco. In the US, cigarette television advertising was banned in the 1970s, but when the ads moved to the press it took more than a decade until print advertisements were eliminated. Then in the 1990s the short-term and ‘soft’ damages caused by smoking were publicised: bad breath, yellow teeth, pimples and poor sports results. Graver health problems were not touched upon (Kluger, 1996/1997). At present people are used to visual warnings on tobacco packaging, which remind them of the harmful effects of smoking. In addition, temporal and spatial restrictions on the sale of alcohol and tobacco products were instituted. In Australia, cigarettes must be sold in standardised brown packs, without any graphic brand elements, only the brand name in standard font. The brown packs are covered with visual and verbal health warnings (see Figure 1.2). The European Union’s new tobacco policy (Directive 2014/40/EU, 2014) has been countered by new market innovations: electronic cigarettes, Internet sales of tobacco products etc.

The tobacco industry and trade organisations try to hinder the enactment of regulations by using political channels (lobbying) and media advocacy, and inventing new ways to normalise practices of tobacco use. More about the disputes between government and business organisations can be found in Chapter 4, section 4.2.3. and Chapter 5, section 5.2. Consumption of new tobacco products has developed in parallel with public condemnation and civic drives against tobacco.

Despite the seeming power of public administration, its hands are tied by the bureaucracy of public programmes and rigidly prescribed ways of monitoring target groups’ actions. As the use of public money is usually strategically planned to fall between political elections, it is not easy to change the way social problems are dealt with. Public officials often face disputes over how public money should be spent. Not only public expectations, but also views of political parties compete. For example, conservative political leaders may be guided by moral beliefs in terms of how social problems should be addressed in public communication. The public sector is also constrained by standardisation. Due to the obligation to treat citizens equally within specific situations, their ability to address individuals whose needs do not fit into pre-determined administrative categories is limited. For example, supporting local employers may be more constructive than paying benefits directly to the unemployed. However, this approach is difficult from the point of view of equal treatment of employers.

Figure 1.2 Example of visual warnings on cigarette packages. Plain packages are used in Australia and are planned for launch in France. Visual warnings on cigarette packs are used in man...