Somaesthetics: A Pragmatist Aesthetic Approach

In the late 1990s, American pragmatist philosopher Richard Shusterman founded a new philosophical discipline that aimed at the cultivation of the body: “somaesthetics,” which offers an understanding of the relationship between mind and body. Shusterman defines the body as “the soma that is both an object in the world and a subject that perceives the world including its own bodily form” (“Body and the Arts” 2). He explains:

The term ‘soma’ indicates a living, feeling, sentient body rather than a mere physical body that could be devoid of life and sensation, while the ‘aesthetic’ in somaesthetics has the dual role of emphasizing the soma’s perceptual role (whose embodied intentionality contradicts the body/mind dichotomy) and its aesthetic uses both in stylizing one’s self and in appreciating the aesthetic qualities of other selves and things.

(Body Consciousness 1)

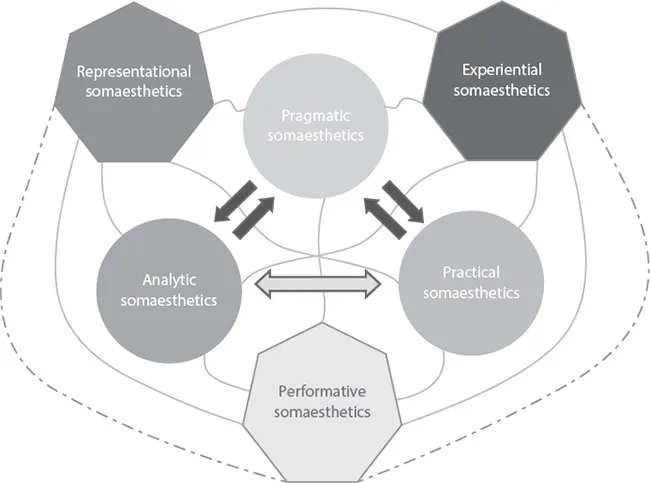

Shusterman builds upon the notion that “perception, language, understanding, and behavior all necessarily rely on a contextual background … in order to achieve their effective meaning and direction” (Thinking 17). There are three basic branches of somaesthetics: First, analytic somaesthetics examines the impact of epistemological, ontological, and sociopolitical issues relating to our “bodily perceptions and practices and their function in our knowledge and construction of reality” (Performing Live 141); second, pragmatic somaesthetics not only presupposes the theoretical branch but prescribes various methods to enhance somatic awareness as a means of changing or remaking the body (142)1; and third, practical somaesthetics applies somatic awareness and experiential embodiment for “heightened somatic sensibility and mastery” (153), used in practices such as Zen meditation, yoga, Alexander Technique, and Feldenkrais Method.2

Shusterman further classifies the branch of pragmatic somaesthetics into three dimensions: representational, experiential, and performative somaesthetics. Representational somaesthetics orientates itself toward external appearance, dealing with the body’s surface forms. On the other hand, experiential somaesthetics’ orientation is toward inner experience. It aims “at making us feel better in both senses of that ambiguous phrase: to make the quality of our somatic experience more satisfying and also to make it more acutely perceptive” (“Designing for Interactive Experience” 21.3.2). These two disciplines are not mutually exclusive; instead, they work interdependently. The third dimension, performative somaesthetics, concentrates primarily on improving inner and/or outer strength, well-being, or skill. Depending on the goal, whether, for external appearances or inner senses of power and skill, the performative discipline may be linked to or assimilated into the representational or experiential dimensions. Furthermore, all three categories of pragmatic somaesthetics interconnect with both theory and practice, enhancing “not only our discursive knowledge of the body but also our lived somatic experience and performance” (Performing Live 21), see Figure 1.1.

Analytic Somaesthetics

On a sociopolitical level, somaesthetics brings the understanding of the encoded somatic habits imposed by hierarchies of power enforced by laws and social norms; for example, how a woman should walk, speak, etc. (Performing Live 140). Shusterman contends with Foucault that the “repressive identities that are encoded and sustained in our bodies … can be challenged by alternative somatic practices” (Shusterman “Foucault” 535).3 Shusterman explains:

As personal feelings of strength and self-awareness feed into more collective feelings of power and solidarity, so individual efforts of consciousness-raising and empowerment through somaesthetics (especially when undertaken with an awareness of the wider social contexts that structure one’s bodily life) can fruitfully contribute to the larger political struggles whose results will shape the somatic experience of women in the future.

(Body Consciousness 99)

In addressing how somaesthetics can help women to “cultivate a sense of power and consciousness,” Shusterman examines Simone de Beauvoir’s somatic philosophy, focusing on her two major works, The Second Sex (1949) and The Coming of Age (1970). In considering “her problematic relationship to somatic cultivation” in relation to the different categories of pragmatic somaesthetics, he finds that “performative-representational somaesthetics activities oriented toward displaying power, skill, and an attractively dynamic self-presentation should promote Beauvoir’s goal of promoting women’s confidence for engaging in greater action in the world” (Body 80, 90). Hence, this book contends that control of the body experienced by the comedia actors helped them not only develop characters on stage, but also in their daily lives.

Shusterman studies Beauvoir’s contribution to analytical somaesthetics and focuses on her “ambiguity,” which he regards as a key concept in her philosophy. He believes that Beauvoir’s “case for woman’s personhood is portrayed as even more problematically divided, because woman, under patriarchy, is not merely torn between body and consciousness but divided within her body itself” (Body 82). Consequently, Shusterman suggests, “such somatic and social subordination is, moreover, incorporated in the bodily habits of these dominated subjects who thus unconsciously reinscribe their own sense of weakness and domination” (Body 78). Feminist theorists have long argued that bodily practices had an effect on women’s domination, and scholars, such as Anne J. Cruz, present a case for the politics of the female body in early modern Spanish literature.4

In somaesthetics, rethinking the Cartesian notion that separates the mind from the body is essential to the understanding of actor and audience bodily reaction. Hippocrates (460–370 BC), who first attributed an individual’s psychological and physical behavior to the four humors, begins a philosophy of body/mind connectivity that is continued by early modern European theorists who believed that passions belonged both to the body and soul. With the increased interest in cognitive studies, we now find multiple approaches to theater and performance studies that focus on “embodiment spectatorship,” such as Bruce McConachie’s work on cognitive approaches to spectatorship (Engaging Audiences 2008) and McConachie and F. Elizabeth Hart (Performance and Cognition 2006), and essays on audience embodiment found in Affective Performance (2013), edited by Nicola Shaughnessy. In comedia studies, Catherine Connor-Swietlicki shows how the “mirror neurons” are interconnected with the body’s response to performance.5 Whether reading or actively watching a performance, “our minds are always dependent on our bodies, their brains and on our individual capacities to experience and interact with everything outside us” (“Embodying” 10).6 Rhonda Blair’s study The Actor, Image, and Action: Acting and Cognitive Neuroscience applies cognitive science and practical techniques to the acting process, highlighting the “pervasive effect that Stanislavsky and his heirs have had on the US view of what acting is and how it should be taught” (10). In view of these recent studies, it is important to implement a cognitive approach to comedia studies in order to shift away from textual accounts of the comedia (which result in an incomplete perspective of early modern Spanish drama that leaves aside essential performative aspects), and embrace an embodied view that considers the fundamental aspects of audience embodiment.

For Shusterman, somaesthetics offers pragmatic practices as a means to enrich embodied experiences and somatic awareness, useful in examining art and performance. He suggests that “on the basic sensorimotor level of perception, if we release from the stress of chronic voluntary muscular contractions, the increased muscle relaxation will allow for heightened sensitivity to stimuli and therefore provide for sharper perception and deeper learning” (“Art as Dramatization” 372), somaesthetic practices that extend beyond the neurosciences of mirror neurons.

Taking into consideration recent studies on mirror neurons, Shusterman examines performance techniques used by the great master of Noh Theater Zeami Motokiyo in Kakyō (“A Mirror Held to the Flower” 1424):

While not concentrating especially on where he is placing his hands and feet, “the actor looks in front of him with his physical eyes” so that he can see the other actors and the audience and thereby harmonize his performance with the full theatrical environment; “but his inner concentration must be directed to the appearance of his movements from behind.” In other words, the actor is performing with an explicit, reflective image of himself, not only his internal image of his somatic bearing (his proprioceptive sense of balance, position, muscle tension, expressiveness, grace, and so forth) but also the image of how he senses he appears to the audience.

(“Body” 140)7

Thus, Zeami emphasizes “self-reflection” as part of the actor’s preparation of performance skills in Noh. In other words, the reflection in the mirror of our memory is what gives us our “I”, explained more in detail in the following section.

Shusterman offers three possible strategies for achieving “self-reflection.” The first technique involves the actor practicing movements in front of a mirror or a set of mirrors, in order to observe the back of his body. By active observation, the actor becomes aware of his posture, movement, and changes in equilibrium, and hence “should be able to infer from his proprioceptive feelings what his posture from the back would look like in actual performance (without using any mirrors), even though he does not strictly see himself from the back” (“Body” 141). The practice of using mirrors to improve one’s physical behavior was seen in seventeenth-century Western theater as well. Speaking through his character Betterton in The Life of Mr. Thomas Betterton (1710), Charles Gildon (1665–1724) suggests a similar exercise, recommending “extensive practice before a mirror to perfect ‘the whole Body likewise in all its Postures and Motions’” (Roach 55).8 The Italian singer and actor Cavaliere Nicolini Grimaldi (1673–1732), also known as Nicolino, prepared himself for a performance by exercising daily in front of a mirror “to practice deportment and gesture” (Roach 68).9 Shusterman considers this exercise “transmodal training through vision and proprioception,” which is connected “through the visuo-motor mirror-neuron system.” He explains:

The visuo-motor mirror neurons discharge both when an individual performs a particular action of motor movement and when the individual simply sees such actions done by others. Such neurons can help explain our natural abilities to imitate and understand others and to communicate with them. But they also provide a way to explain our basic powers of integrating visual and motor-proprioceptive perceptions. (141–42)

In the context of early modern Spanish studies, Catherine Connor-Swietlicki, reminds us that whether reading or actively watching a performance, “our minds are always dependent on our bodies, their brains and on our individual capacities to experience and interact with everything outside us” (“Embodying” 10). She proposes that we examine the body’s response to performance in relation to mirror neurons, a type of brain cell that responds both when a person acts and when the person observes the same action performed by another, which leads us to the second technique, “other oriented” or “transpersonal.”

This second exercise entails the actor taking the role of the audience, “empathetically” observing another individual’s movements, which would then stimulate “not only areas of the brain similar to those involved in the movement itself but also to activate muscular and other physiological responses related to such a movement or action” (Shusterman Body 142). In early modern Spain, exercises in observation were practiced by preachers in preparation for their ‘role’ on the pulpit. For example, for exercises on power of persuasion, Fray Luis de Granada’s Ecclesiasticae Rhetoricae (1575; Ecclesiastical Rhetoric) employs a “transpersonal” technique, advising preachers to pay attention to the animated gestures of the old ladies arguing in the market in order to imitate their movements on the pulpit (Flor 146). Others, such as Fray Diego Niseno, maintain that “the preacher, like the actor, must excel in portraying different characters ‘on stage’ to produce calculated responses in his listeners and take special care not to destroy the illusions he creates at the end of the performance” (Barnes-Karol 60). In addition, this exercise expected priests to produce a visual image of how they would look like before depicting ‘their characters’ onstage, which corresponds to the third category.

The third technique requires the actor to rely on his own “proprioceptive self-observation of his posture or movement,” as opposed to mirrors or input from others, to produce a “visual image in his mind of how his pos...