- 396 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Printed images were ubiquitous in early modern Britain, and they often convey powerful messages which are all the more important for having circulated widely at the time. Yet, by comparison with printed texts, these images have been neglected, particularly by historians to whom they ought to be of the greatest interest. This volume helps remedy this state of affairs. Complementing the online digital library of British Printed Images to 1700 (www.bpi1700.org.uk), it offers a series of essays which exemplify the many ways in which such visual material can throw light on the history of the period. Ranging from religion to politics, polemic to satire, natural science to consumer culture, the collection explores how printed images need to be read in terms of the visual syntax understood by contemporaries, their full meaning often only becoming clear when they are located in the context in which they were produced and deployed. The result is not only to illustrate the sheer richness of material of this kind, but also to underline the importance of the messages which it conveys, which often come across more strongly in visual form than through textual commentaries. With contributions from many leading exponents of the cultural history of early modern Britain, including experts on religion, politics, science and art, the book's appeal will be equally wide, demonstrating how every facet of British culture in the period can be illuminated through the study of printed images.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Printed Images in Early Modern Britain by Michael Hunter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Weltgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

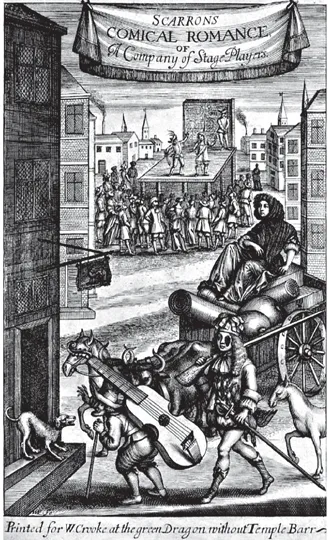

1.1 Engraved title-page by William Faithorne to Scarron’s Comical Romance: Or, a Facetious History of a Company of Strowling Stage-players (London, 1676).

1

Introduction

Printed images were ubiquitous in early modern Britain. Mainly emanating from producers and dealers in London but penetrating throughout the country, such images ranged from engraved portraits to playing cards and maps, from topical broadsheets to genre scenes or pattern books depicting birds and animals. Wherever they were to be found, they served a multiplicity of purposes in people’s lives, from the functional to the recreational or decorative: even the rooms of homes might be adorned with prints pinned up on the walls or with ornamental features copied from them, while specially printed wallpaper was a further medium which originated at this time. Pictures also featured prominently in printed books of the period, ranging from simple woodblock scenes and diagrams to series of engraved plates. Perhaps most typical of the period were elaborate title-pages which sought to encapsulate the theme of a work by emblematic or illustrative means. The example reproduced here, which gives a sense of the ethos of travelling theatre at the time, is William Faithorne’s frontispiece to the English version of Paul Scarron’s Comical Romance: Or, a Facetious History of a Company of Strowling Stage-players (London, 1676). (Fig. 1.1)

Such images are often visually striking, frequently conveying powerful messages which are all the more important for having circulated widely at the time. In addition, their range is broad, from high art to crude satire: much can therefore be learned from them about tastes and ideologies at many levels of contemporary society. Yet, by comparison with the texts with which they are often juxtaposed, the printed images that have come down to us from early modern Britain have until recently been surprisingly neglected, even by students of aspects of the history and culture of the period to whom they ought to be of the greatest interest. The object of this book is to help to rectify this state of affairs by offering a conspectus of the kind of interpretative work that such images invite; it is hoped that it will thereby encourage greater exploitation of this key source for the history of the period.

It stems from a pair of conferences organised under the auspices of the AHRC-funded British Printed Images to 1700 project, which ran from 2006 to 2009. The primary aim of this collaborative project was to create a fully searchable online database of printed images of the period, and a note on this appears at the end of this introduction. However, an ancillary aim was to encourage innovative research on printed images from early modern Britain, and to this end two conferences were held, the first at Birkbeck, University of London, on 13–14 July 2007 and the second at the Victoria and Albert Museum on 12–13 September 2008. The papers that are presented in this volume were all given at one or other of those conferences, and they are indicative of the lively research now in progress on a whole range of printed images dating from the aftermath of the Reformation to the early Augustan era.1

In origin, the production of printed images in Britain as elsewhere in Europe goes back to the late Middle Ages. Indeed, it could be argued that the invention and dissemination of such techniques was as crucial an innovation as the introduction at much the same time of the use of moveable type, the impact of which has been the subject of so much scholarly attention in recent years.2 The role of images in this connection was asserted particularly by William M. Ivins, Jr., in his prescient if idiosyncratic book, Prints and Visual Communication (1953), in which he claimed that the ability to create ‘exactly repeatable pictorial statements’ was one of the great revolutions in the history of Western culture.3 He also rightly saw that the significance of prints far transcended the art-historical context in which they had traditionally been studied, even if some of his preoccupations now seem a little dated.4

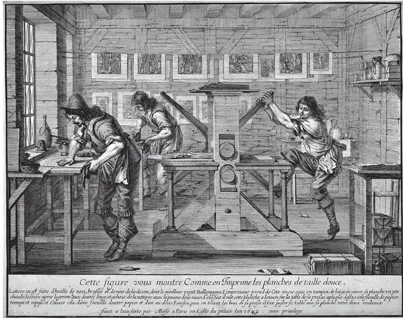

In terms of doing justice to the overall significance of early printed images, matters have been complicated by the extent to which these fall into two main types, namely the woodblock and the intaglio, which have tended to be studied separately. There is a certain appropriateness to this insofar as they were executed and printed using different techniques and processes, thus entailing a different relationship with printed texts. While woodblocks involved the production of a raised surface which could be inked and printed on the same press as type, engravings and etchings involved the reverse process, with the design being incised on a metal plate from the surface of which the ink was wiped prior to printing, meaning that a different type of press, the rolling press, was required to produce impressions from it.5 The latter process is classically represented in Abraham Bosse’s famous 1642 etching of a printmaker’s shop in which workmen respectively ink the plate, wipe it and put it on the press. (Fig. 1.2) Yet even if this distinction explains why study of the products of the two techniques were often studied separately in the past, it only partly explains the extent to which such studies have remained distinct even in more recent times, and to understand this broader contrasts in scholarly preoccupations need to be invoked.

On the one hand, we have the tradition of the study of engravings as part of the mainstream of European art going back to Adam Bartsch’s catalogue of early modern prints, Le Peintre Graveur, published in 21 volumes between 1803 and 1821. As his title betrays, Bartsch placed the greatest value on prints that could be seen as original works by major artists, and this tradition of connoisseurship in relation to printed images still remains important, especially in the print rooms of major museums in which such outstanding, single-sheet prints are most often conserved. Among Bartsch’s successors in an English context, perhaps the most notable was Arthur M. Hind, who long worked in the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, of which he was Keeper from 1933 to 1945. Though Hind’s works included studies of woodcuts, particularly from fifteenth-century Germany, the bulk of his writings were on engravings. He followed up his successful Short History of Engraving and Etching (3rd edn, 1923) not only by more detailed studies of Italian and other engravers but also by an ambitious attempt to write a complete account of engraving in England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In this, he intended to give a descriptive account of the corpus of successive artists active in England during the period, and the first volume, dealing with the Tudor period, appeared in 1952, while the second, covering the reign of James I, followed in 1955; a third volume, dealing with the reign of Charles I, was published from Hind’s materials after his death in 1964, but at that point the enterprise came to an end.6

1.2 Abraham Bosse, etching of printmaker’s workshop, 1642.

Hind’s achievement was a remarkable one, but it is revealing that it was to engraved work that he restricted himself. Other attempts to give comprehensive accounts of British printed images from the period have been even more restricted in their remit, the most significant being limited to mezzotints, a variant on the normal process of engraving which reverses the technique and produces a more tonal effect echoing that of an oil painting; it hence fitted even more naturally into the tradition of art connoisseurship.7 It is perhaps worth adding that, since such techniques were most typically used to produce portrait prints, these have tended to dominate catalogues and studies emanating from this tradition.

By comparison, the woodcut has mainly been studied as an emanation of popular culture. To an extent, this goes back to the Victorian period, when various antiquaries published collections of broadside ballads and chapbooks, often including reproductions of the woodblock illustrations that they contained, though these tended to be seen as rather incidental to the texts they accompanied; this tradition was continued by scholars such as Hyder E. Rollins in the 1920s and 1930s.8 More recently, studies of the collection of such artefacts made by Samuel Pepys have paid greater attention to their illustrations, while this is still more the case with the Bodleian Library’s online Broadside Ballads Project: this offers 30,000 ballads in fully indexed form, including the facility to search their images using ICONCLASS, the iconographic system developed by Dutch art historians over the past half-century which offers a complete classification of the subject matter of Western art.9

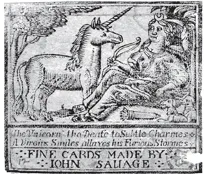

A further development has been of interpretative studies, seeking to use woodcut images to draw conclusions about popular ideologies in the period. Of these, one of the earliest and most important was concerned not with English material but German, the late Robert W. Scribner’s pioneering For the Sake of Simple Folk: Popular Propaganda for the German Reformation (1981), a truly remarkable work which drew on the rich imagery of pro- and counter-Reformation polemic in Germany to give a quite novel visual dimension to our understanding of Luther’s revolt against Rome and its aftermath.10 In the English context an equally notable work was Tessa Watt’s Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550–1640 (1991), which for the first time gave proper attention to the range of popular imagery that survives in printed form from the period before the Civil War, particularly from the Jacobean period onwards, when there was an upsurge of material of this kind.11 This has since been followed by other works, notably Sheila O’Connell’s The Popular Print in England (1999), which was associated with an important exhibition at the British Museum and which, though ranging more widely chronologically, gives a powerful sense of the market that existed for cheap and often crudely produced images in the early modern period, and the ways in which producers catered for this.12 An example is provided by such items as the naive evocation of Diana and the Unicorn that the late seventeenth-century dealer John Savage thought appropriate to the wrapper of a pack of playing cards. (Fig. 1.3)

In parallel with this, there has been a growing interest in book illustrations, especially those in Foxe’s ‘Book of Martyrs’, by far the most striking illustrated book to be produced in Tudor England. Margaret Aston, Elizabeth Ingram, Thomas Betteridge and others have illustrated how aware Foxe himself was of the power of images in putting across his message, including the pictorial ‘shock tactics’ involved in the martyrdom scenes that are such a striking feature of his book; and this message has been underlined by John N. King in his recent Foxe’s ‘Book of Martyrs’ and Early Modern Print Culture (2006), which emphasises the unprecedented scale and effectiveness of the illustrations to this work.13 Indeed, the fact that Foxe’s ‘Book of Martyrs’ has already received so much attention from this point of view may help to excuse the fact that no essay in the current volume is directly devoted to it, although John King spoke on an aspect of its illustrations at the conference at the V&A in September 2008, while Margaret Aston comments on successive versions of its title-page in Chapter 2.14

1.3 Wrapper to a pack of playing cards issued by John Savage (active 1683–1700).

In recent years, other sixteenth-century illustrated books have also received attention, and we now have a complete catalogue of English book illustrations of this period in the form of Elizabeth Ingram and Ruth Luborsky’s Guide to English Illustrated Books, 1536–1603 (1998) (a continuation of Edward Hodnett’s much earlier English Woodcuts, 1480–1535 (1935)).15 On the other hand, the relative profusion of material that now exists for the period to 1603 makes all the more glaring the lack of comparable resources in relation to the burgeoning use of book illustration after 1604.16 Virtually the only exception is the pioneering analysis of a selection of engraved title-pages by Margery Corbett and Ronald Lightbown in The Comely Frontispiece (1979).17 In addition, there has been sustained attention to the genre of emblem books, which, though Continental by origin, had a significant British emanation in this period which has been the subject of considerable recent scholarly interest.18

As far as seventeenth-century British printed images are concerned, a landmark was represented by an extraordinary book published by the Canadian academic Alexander Globe in 1985. Entitled Peter Stent, London Printseller, c. 1642–1665: Being A Catalogue Raisonné of His Engraved Prints and Books with an Historical and Bibliographical Introduction, this was inspired by the two advertisements of prints for sale that the dealer Peter Stent issued in 1654 and 1662. These were used as the basis for a meticulous analysis of Stent’s stock, the engravers who worked for him and the often complex history of the works they produced.19 What was remarkable about Globe’s book was that many of the products with which it dealt were cheap and ephemeral, more similar to the broadside ballads and the like that had interested students of popular culture than to the sophisticated prints that had formerly interested art historians: even the copies of images from Van Dyck’s Iconography that Stent commissioned were cut down in size, with ‘two Heads in a Plat’, to make them accessible to a wider audience. (Fig. 1.4) In addition, the fact that Globe’s treatment was based on Stent’s advertisements means that many of the works that he tabulated do not survive at all, a reminder of the extent to which our knowledge of material of this kind is skewed by the accidents of survival. Above all, Globe stressed the topicality and ma...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- List of Illustrations

- 1 Introduction

- Printed Images and the Reformation

- Printed Images in Science and Cartography

- Printed Images and Politics

- Printed Images and Aspects of Late Seventeenth-century English Culture

- Index