March 11, 2011 is the date of one of the largest earthquakes in recorded history. At 2:46 in the afternoon plate movements deep below the ocean surface in the subduction zone off the northeastern coast of Japan triggered long and violent quaking across an extremely wide area. The displacement of water caused by the initial plate movement gave rise to a tsunami that effortlessly washed over the defenses of the Tohoku coast, claiming countless victims, devastating entire communities, and resulting in one of the largest nuclear disasters the world has seen. The complex interweaving of this massive earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident has become known to the world as the Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster. While nearly all of the chapters in this book deal directly with this complex disaster, this chapter returns to the precipitating event—the earthquake off the Pacific coast of Tohoku (hereafter, “2011 Tohoku Earthquake”)—in order to outline its geophysical sources and ongoing seismic effects.

It is not uncommon for past earthquakes to be framed as momentary, finite, and now finished events. The reality is, however, that aftershocks and other crustal movements resulting from a magnitude 9 class earthquake such as the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake can continue for well over a decade. Accordingly, it is imperative that our efforts to understand and respond to the Fukushima nuclear accident are advanced upon a foundational examination of the geophysical event that triggered this disaster and continues to sustain increased seismicity in the region. This chapter takes up this task by examining the geophysical dynamics of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake, focusing specifically on the mechanisms of the foreshock and mainshock as well as predicted future seismicity in the form of aftershocks and induced earthquakes.

Foreshocks and mainshock

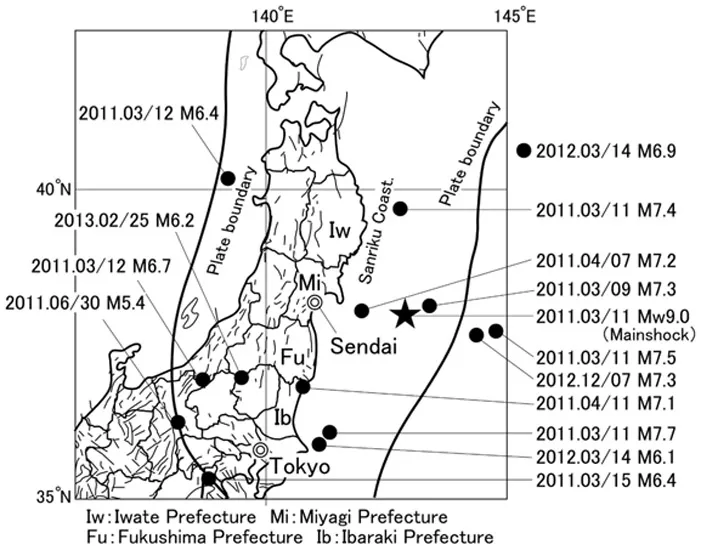

The earthquake that occurred at 2:46 pm on March 11, 2011 was an Mw9.01 earthquake, the fourth largest earthquake in world history since the twentieth century began. While the mainshock of this earthquake occurred off the coast of Miyagi Prefecture (Figure 1.1), around one month before this mainshock a site 50 km north of the epicenter of this mainshock became highly seismically active. Over the following weeks this seismic activity gradually shifted southward, and two days before the mainshock, on March 9, 2011, a M7.3 earthquake occurred 20 km north of the epicenter of the mainshock (Kato et al. 2012). This earthquake produced a 50 cm tsunami that damaged oyster farms off the Sanriku Coast. The magnitude of this earthquake led seismologists to initially identify it as a main-shock. In retrospect, however, seismologists now believe that this was a foreshock of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake.

Figure 1.1 Epicenters of foreshocks, mainshock, aftershocks, and induced earthquakes related to the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake.

The shaking caused by the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake was felt across almost all of Japan, excluding Okinawa Prefecture and a portion of Kyushu. On the Japan Meteorological Agency seismic-intensity scale the quake was measured as a 7—the highest level and one at which people are violently thrown by the shaking and most residences will collapse—in Osaki City in Miyagi Prefecture and as a 6-upper—the second highest level and one at which it is impossible to stand and many residences will collapse—across a wide area stretching from Iwate Prefecture to Ibaraki Prefecture. While the shaking in Tokyo was measured only as a 5-upper on the Japan Meteorological Agency seismic-intensity scale, the long duration and intensity of the shaking caused extensive damage, including bending the tip of Tokyo Tower. Frequent aftershocks followed, including a M7.5 aftershock off the coast of Iwate Prefecture 15 minutes after the mainshock and a M7.7 aftershock off the coast of Ibaraki Prefecture 30 minutes after the main-shock (Asano et al. 2011; Huang and Zhao 2013). Even today, over four years after the mainshock, this area continues to be highly seismically active.

Aftershocks and remotely triggered earthquakes

Following the mainshock of March 2011 a large number of small to large earthquakes occurred, primarily throughout eastern Japan. These earthquakes can be classified into several types based on their characteristics, including 1) aftershocks occurring along the plate boundary of the Japan Trench, 2) remotely triggered normal-fault earthquakes occurring inland near the boundary between Fukushima and Ibaraki prefectures, 3) remotely triggered earthquakes occurring in areas distant from the epicenter of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake, and 4) outer-rise earthquakes occurring beyond the Japan Trench.

Earthquakes of the first type—aftershocks occurring along the plate boundary of the Japan Trench—include the M7.4 earthquake off the Iwate coast and the M7.7 earthquake off the Ibaraki coast that occurred on the same day as the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake, as well as the M7.2 earthquake that occurred off the Miyagi coast on April 7, 2011, nearly one month after the mainshock. One previous earthquake that it is highly important to consider when thinking about future seismic activity off the coast of eastern Japan is the M9.1 Sumatra Earthquake of 2004. The mainshock of this earthquake occurred on December 26, 2004, and it was followed over approximately the next ten years by over 10 earthquakes in the 7–8 magnitude class. A similar mechanism lay behind both this earthquake and the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake. Both quakes occurred at plate boundaries and were low-angle reverse-fault type earthquakes. As with the Sumatra Earthquake, frequent aftershocks as well as remotely triggered earthquakes followed the mainshock of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake, and even now this area continues to be highly seismically active. Accordingly, it is probable that large-scale aftershocks will continue to occur for a number of years in the area off the coast of eastern Japan.

In general, the largest of aftershocks tends to be around a full digit in magnitude less than the magnitude of the mainshock; therefore, the Mw9.0 mainshock of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake could give rise to quite large M8 aftershocks. The largest aftershocks tend to occur most frequently at the end of the fault source because the amount of fault displacement at the time of the mainshock varies according to location along the fault, with the largest amount of fault displacement tending to occur near the center of the fault. For example, the M7.0 earthquake in Sichuan, China on April 20, 2013 occurred along the same Longmenshan fault zone where the M8.0 Great Sichuan Earthquake occurred on May 12, 2008. The 2013 earthquake was likely an aftershock of the Great Sichuan Earthquake of 2008. In the case of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake there was also a very large difference between the amount of displacement at the center of the fault (maximum 20–30 m) and the amount of displacement at the ends of the fault (less than a few meters), and thus there are concerns that a large aftershock may occur in the future at either end of the fault source off the coasts of Iwate and Ibaraki prefectures. In addition, since the southernmost aftershocks from the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake have occurred along the northern edge of the Philippine Sea Plate, it has been pointed out that this plate obstructed the southward advancement of crustal rupturing toward the coast of the Boso Peninsula. What this suggests is that, while on one hand the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake subsided with an Mw9.0 scale earthquake, on the other it has added a great amount of pressure to the northern edge of the Philippine Sea Plate.

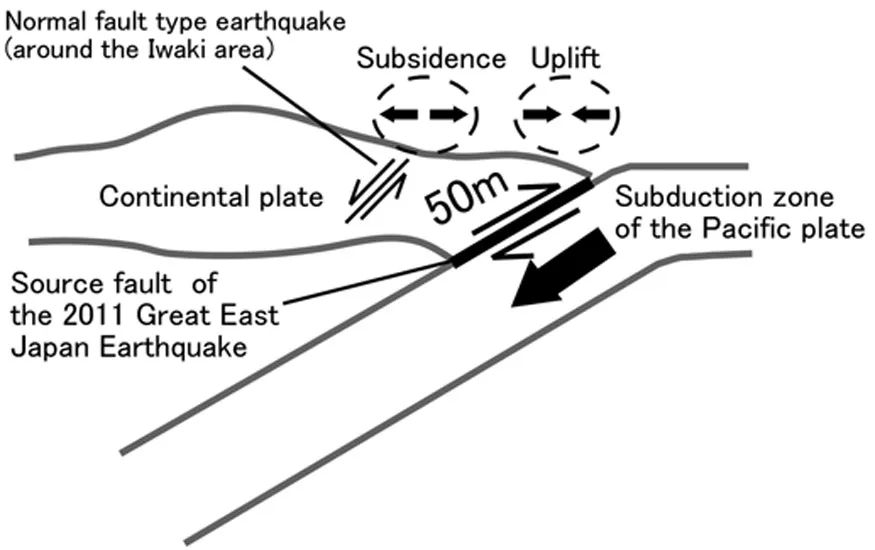

The second type of earthquake that occurred following the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake—remotely triggered normal-fault earthquakes occurring inland—was caused primarily by tensile stress on normal faults (Figure 1.2), as represented by the high level of seismic activity that appeared in northern Ibaraki Prefecture and in the coastal Hama-Dori region of Fukushima Prefecture. While these earthquakes were nearly completely absent prior to the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake, they began to occur frequently after March 11, 2011 (Okada et al. 2011).

The 2011 Tohoku Earthquake was a plate-boundary earthquake, meaning that it occurred where a continental plate (i.e. the Eurasian Plate) is lifted over an oceanic plate (i.e. the Pacific Plate). As a result of this quake the fault moved roughly 50 m, and, additionally, since this is a low-angle fault, the horizontal movement of the fault was many times greater than its vertical movement (Figure 1.3). Accordingly, the areas to the west of the fault source were pulled toward the fault (the “uplift” zone in Figure 1.3). For example, the Oshika Peninsula of Miyagi Prefecture moved 5.3 m eastward as a result of this movement. However, since the absolute volume of the continental crust was not altered by this horizontal movement, the uplift of the continental crust in the vicinity of the fault induced an east–west tensile stress, “pulling in” the continental crust from the areas further west of the source fault. Consequently, the crust became thinner and subsidence resulted in these areas, which appears to be the cause of frequent normal-fault earthquakes in the northern portion of Ibaraki Prefecture and in the coastal Hama-Dori region of Fukushima Prefecture.

Figure 1.2 Diagrams of normal and reverse faults.

On April 11, 2011, one month after the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake, the M7.0 (Mw6.6) Fukushima Hama-Dori Earthquake, with its epicenter in Iwaki City, occurred, and the Hama-Dori and Naka-Dori regions of Fukushima Prefecture, as well as the southern region of Ibaraki Prefecture, experienced shaking of 6-lower on the Japan Meteorological Agency seismic-intensity scale. Seismic activity remained strong in this area after the earthquake, and on September 20, 2013, roughly two and a half years after the Hama-Dori Earthquake, a M5.9 earthquake, again with its epicenter in Iwaki City, occurred, and shaking of 5-upper was recorded in Iwaki City. During the Hama-Dori Earthquake, landslides led to the deaths of four individuals, and Iwaki City experienced serious damage less than a month after the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake. This earthquake was caused by the movement of the Idosawa and Yunodake Faults, whose presence was previously only assumed from their geomorphologic characteristics. The active presence of these faults has now been confirmed by the emergence of a clear normal fault along west of the Idosawa Fault (Lin et al. 2013). The results of a trench-excavation survey of the normal fault created by this earthquake indicated that the most recent activity of this fault prior to the Hama-Dori earthquake was 12,620 to 17,410 years ago (Toda and Tsutsumi 2013). Because it was not possible to find traces of movement at the time of the Jogan Earthquake of 869, it can be said that no earthquakes have occurred on this fault as a result of large earthquakes occurring at the Japan Trench. This indicates that the faults along the Idosawa Fault have been moving independently of large earthquakes along the Japan Trench, suggesting that due to conditions at the time a fault may have been moving parallel to the Idosawa Fault.

Figure 1.3 The mechanism behind the normal-fault-type earthquakes in the coastal areas of Fukushima and Ibaraki prefectures.

The third type of earthquake that occurred following the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake—remotely triggered earthquakes in areas distant from the epicenter of the mainshock—includes such earthquakes as the M6.7 earthquake that occurred the following day in northern Nagano Prefecture, the M6.4 earthquake that occurred on March 15, 2011 in eastern Shizuoka Prefecture, the M5.4 earthquake that occurred on June 30, 2011 in central Nagano Prefecture, and the M6.2 earthquake that occurred on February 25, 2012 in northern Tochigi Prefecture. During the northern Nagano Earthquake of March 12, 2011, Sakae Village, located near the epicenter of the quake, experienced shaking of 6-upper on the Japan Meteorological Agency seismic-intensity scale, and the Tsunan area of Tokamachi City experienced shaking of 6-lower. While this earthquake forced 1,700 individuals from Sakae Village, over 80 percent of the population, to evacuate, the high degree to which public attention across the nation was centered on the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake Disaster meant that the impacts of this disaster went largely unreported by the media. The eastern Shizuoka Earthquake that occurred four days after the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake was recorded as a 6-upper shaking in Fujinomiya City, Shizuoka Prefecture, and 50 individuals were injured. Since the epicenter of this earthquake was directly over the magma chamber of Mt Fuji, volcanologists were concerned that an eruption was immanent. Fortunately, however, no eruption of Mt Fuji has yet occurred following the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake.

The central Nagano Earthquake of June 30, 2011 occurred directly under the highly populated city of Matsumoto. Over 4,000 cases of structural damage were reported, and one individual lost their life. While this earthquake was initially thought to have been generated by the active Gofukuji fault of the Itoigawa Shizuoka Tectonic Line, detailed analysis of the location of the epicenter indicated that it occurred at the far west of the Akagi Fault, which branches off from the Gofukuji Fault (it is possible that these two faults are connected underground). In the case of the earthquake that struck northern Tochigi Prefecture on February 25, 2012, shaking of 5-upper on the Japan Meteorological Agency seismic-intensity scale was recorded, and an avalanche resulting from the earthquake caused guests at a hot-springs resort to be temporarily blocked in. Mt Nasu and Mt Nikko-Shirane are located in this area, and it is one of the areas in Japan with the highest number of volcanoes. Since the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake resulted in increased seismic activity in an area stretching from Hokkaido to Kyushu that contains 20 volcanoes (in 2014, two of these, Mt Ontake and Mt Aso, erupted), it is imperative to continue to observe this seismic activity in volcanic regions.