eBook - ePub

Common Land, Wine and the French Revolution

Rural Society and Economy in Southern France, c.1789–1820

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Common Land, Wine and the French Revolution

Rural Society and Economy in Southern France, c.1789–1820

About this book

Recent revisionist history has questioned the degree of social and economic change attributable to the French Revolution. Some historians have also claimed that the Revolution was primarily an urban affair with little relevance to the rural masses. This book tests these ideas by examining the Revolutionary, Napoleonic and Restoration attempts to transform the tenure of communal land in one region of southern France; the department of the Gard. By analysing the results of the legislative attempts to privatize common land, this study highlights how the Revolution's agrarian policy profoundly affected French rural society and the economy. Not only did some members of the rural community, mainly small-holding peasants, increase their land holdings, but certain sectors of agriculture were also transformed; these findings shed light on the growth in viticulture in the south of France before the monocultural revolution of the 1850s. The privatization of common land, alongside the abolition of feudalism and the transformation of judicial institutions, were key aspects of the Revolution in the countryside. This detailed study demonstrates that the legislative process was not a top-down procedure, but an interaction between a state and its citizens. It is an important contribution to the new social history of the French Revolution and will appeal to economic and social historians, as well as historical geographers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Common Land, Wine and the French Revolution by Noelle Plack in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Mise en Scène — the Department of the Gard

Environment and Topography

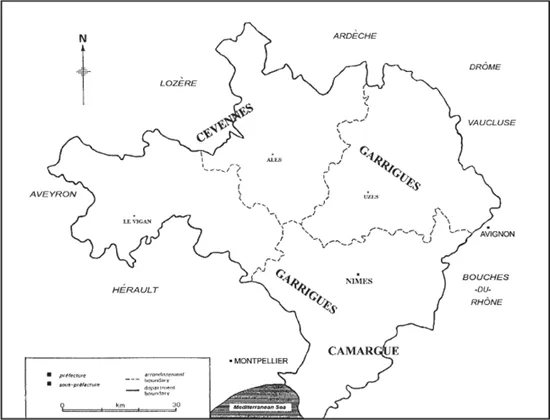

The Department of the Gard was created in February 1790 when the National Constituent Assembly refashioned the internal administrative boundaries of France. The Gard was formed along with eight other departments from the old province of Languedoc, and took its name, like so many other new departments, from a principal river, the Gardon, which transects the region flowing east to west (see Map 1). The total surface area of the department is some 5,800 square kilometres – roughly 120 kilometres from east to west and 108 kilometres from north to south. The Gard is bordered to the north by the departments of the Ardèche and Lozère and to the east by the Aveyron and Hérault; the mighty Rhône river forms the western boundary, while the Mediterranean coast delineates its southern extreme for 20 kilometres. The chef-lieu of the Gard is Nîmes, which was founded by the Phoenicians, but really developed as an administrative centre during the Roman Occupation. Indeed, it is impossible to ignore the Gard’s classical heritage, not only did this territory form a significant part of Roman Gaul, but was also at the heart of the route from Italy to Spain. Nîmes itself is called the ‘Rome of France’ with its incredibly well-preserved amphitheatre and Maison Carrée; while the Pont-du-Gard, the aqueduct built by the Romans to bring water to Nîmes, thus solving one of its basic problems, remains one of the greatest architectural engineering feats of western civilization.

Map 1 The Department of the Gard, c.1800

The environment and topography of the Gard are extremely diverse. The region is made up of three parallel zones: the Mediterranean coastal plain, the garrigue hillsides, and the Cévennes Mountains. A tour of the physical terrain begins along the narrow coastline which is made up primarily of sand-bars and salt marshes and forms part of the Camargue. This area, which is the mouth of the Rhône delta, is marked on the west by the Vidourle River, while the Petit Rhône forms its eastern border in the Gard. The Camargue is an expanse of marshes, lakes and ponds, with various étangs (lagoons) at its heart. In the twentieth century the area experienced much land reclamation, especially in the north, where vines and rice-fields have been planted. Some of the Camargue is a designated nature reserve, home to halfwild cattle and horses, herons and flamingos. The Camargue then gives way to the Mediterranean coastal plain, which is a belt of highly fertile alluvial land. This fertile coastal plain sweeps across the entire region of Lower Languedoc from the Hérault in the west to the Rhône in the east, but only has a width of 15-20 kilometres. Mineral springs are common in this area. The most famous spring is the one at Vergèze in the Gard’s coastal plain, which produces an aerated water sold under the name of Perrier.1

The Camargue and fertile coastal plain soon give way to the garrigue. The garrigues, from the Catalan garric, represent the most common landscape in the Mediterranean world and are the by product of burning and grazing forests.2 The vegetation is made up of low scrub, usually no more than a half a metre tall, which grows in calcareous (derived from limestone) as opposed to silicacious (sandy or silica-based) soil. There are hundreds of plants which flourish in the garrigue, including aromatic ones like lavender, sage, rosemary and thyme.3 Because they were created over the centuries by shepherds, who burned woodland to produce the vegetation they needed to pasture their flocks, the garrigues themselves are symbol of human-induced ecological change throughout the millennia.4 Within the Gard, there are several distinct garrigue zones, each one separated from the others by fertile river valleys or bassins. Hence, the Vistre, Gardon and Cèze rivers are flanked by distinct sections of garrigue. One of them, the Garrigue de Nîmes, is an ensemble of calcified hills and a plateau, reaching a summit of 200m and forming a band 40km long to the north of the chef-lieu.5

In the west and north-western sections of the department, the Cévennes Mountains begin.6 The harsh, rugged, steep hills intermixed with damp and narrow valleys stretch from Le Vigan in the west to Privas in the department of the Ardèche in the north. Many important rivers begin in the Cévennes, among them are the Loire, Allier, Tarn, Aveyron, Gardon and Hérault. The rugged, jagged rock of the Cévennes is generally igneous granite, metamorphic rocks or the products of volcanic activity such as lava. The climate in the Cévennes is the most severe in the department. The winters, which are extremely harsh, begin in November and are at their worst in January and February. Frost and snow are unpredictable during the winter months and might occur at any time. From March onwards, clouds, mist and rain are not uncommon, but there is also hot sunshine in summer months. Coming down from the Cévennes and into the garrigues and coastal plain the weather rapidly improves. However, the whole region is subject to the ferocious wind, known as the mistral, which is a strong dry cold wind that blows down the Rhône valley. Most of the annual rainfall in the garrigues and coastal plain occurs from the autumn through the spring, with the winter months being fresh, but not particularly cold – the average temperature in January is between 5°-6.5°C.7

Given this harsh and diverse landscape, it is unsurprising that at least half of the Gard’s land is unsuitable for arable cultivation being dominated either by the marshes of the Camargue, the garrigues or the Cévennes. Several contemporaries have commented on this infertility. Arthur Young, the great English agronomist, travelled through the region in the summer of 1787 and remarked that

The vast province of Languedoc, in productions one of the richest in the kingdom, does not rank high in the scale of soil; it is by far too stony. I take seven-eighths of it to be mountainous. The productive vale from Narbonne to Nîmes is generally but a few miles in breadth, and considerable wastes are seen in most parts.

In travelling from Narbonne to Béziers, Pézenas, Montpellier and Nîmes, everyone I conversed with represented that vale as the most fruitful in France. Olives and mulberries, as well as vines, render it very productive, but in point of soil much the greater part of it is inferior…8

While in 1800 S.V. Grangent, the Gard’s chief engineer, estimated that

Almost half of the surface area is covered by sterile mountains, unproductive woods…uncultivated marshes and many garrigues which hardly produce any feed for the herds (of livestock).9

How this inhospitable landscape with its ‘inferior’ soil constrained and shaped the contours of the regional economy is the next topic of investigation.

The Regional Economy

Like much of France during this period, the Gard’s economy was dominated by agriculture. The department was part of a larger agricultural region where the practice of petite culture dominated.10 This system was characterized by peasantowned smallholdings, which were cultivated with neither horses nor heavy ploughs. On the whole, from the late eighteenth to the early nineteenth centuries, a general reduction of grain and olive cultivation and rise in viticultural production may be detected. But in spite of this and the unforgiving, rocky, infertile soil, the peasants of the Gard were still able to produce one-third of the grain needed for consumption.11 The rest was either imported from northern departments (Côte-d’Or, Ain, Saône et Loire) or from the Haute-Garonne or the Aude. Of the grain that was produced within departmental boundaries, that of Saint-Gilles in the fertile coastal plain was the most esteemed. While wheat was the primary crop, it was not the only type of grain produced, for rye, oats, barley and millet were also cultivated. Various types of legumes (peas, beans, and lentils) were grown, but again not enough to meet subsistence needs so they were often imported from the neighbouring Ardèche. Corn does not seem to have been cultivated on a large scale, but the potato was successfully grown and proved to be a staple foodstuff of poorer peasants. In the Cévennes, because the steep slopes and wet climate were unsuitable for growing wheat, rye and barley were cultivated, while chestnut trees were extensively planted and used in remarkably diverse ways, earning them the nickname l’arbre à pain.

If grain cultivation did not dominate the agricultural landscape as it did in other regions of France it was because Lower Languedoc had always been dominated by polyculture. The originality of southern polyculture was that it ensured a better-balanced diet with bread, wine, olive oil, chestnuts, garden vegetables and dried fruits.12 In July 1787, Arthur Young noted that ‘every man has an olive, a mulberry, an almond, or a peach-tree, and vines scattered among them’.13 Within this very succinct observation, Young had described the major components of polyculture in the Gard. According to the Gard’s chief engineer during the Consulate, S.V. Grangent, wine was the principal agricultural product of this department by 1800.14 Vines were grown everywhere and seemed the natural crop for the environment, especially in the garrigues as the highly calcified soil aided vine cultivation and the wild herbs, such as rosemary and thyme, added distinct properties to the grapes. The only place that they did not grow was in the higher mountain regions of the Cévennes around Le Vigan and Saint-Jean-du-Gard.

Although wine grapes had been grown in this region since at least the Roman Occupation, from the late sixteenth century viticulture had been slowly on the rise in the Gard, transforming the focus of cultivation from grain to vines.15 The real boom came in the mid-eighteenth century when the legal impediments were removed and more land became available after the clearance edict of 1770.16 In fact, after the edict of 1731, which prohibited the pla...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Maps

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction The French Revolution, the Peasantry and Village Common Land

- 1 Mise en Scène – the Department of the Gard

- 2 From Liberal to Radical Revolution, 1789–1792

- 3 The Jacobin Revolution, 1793

- 4 Post-1793: Backlash and Regularization

- 5 The Empire and Beyond

- 6 The Socio-economic Impact of Common Land Reform

- Conclusion

- Appendix I Application of the Law of 9 Ventôse XII in the Gard

- Appendix II Sales by Commune under the Law of 20 March 1813 in the Gard

- Bibliography

- Index