![]()

p.1

1 Introduction

Global mobilities

Amy K. Levin

In June 2015, I traveled to Milan to visit the headquarters of the MeLa Project (European Museums in an Age of Migrations) at Politecnico di Milano. Staying a few steps from the main city station, Milano Centrale, I found myself in the heart of my research on public displays related to migration. The plaza in front of the ornate “Mussolini Modern” station was transformed into an informal camp for migrants from North Africa seeking entry to the rest of Europe. Hundreds of men, women, and children occupied grassy spots—especially where trees provided shade—circling mounds of luggage to protect it from theft. Women washed clothes in buckets and stretched them across bushes to dry. One man sought partial cover behind bushes as a friend poured cold water on him from a bucket so he could bathe. Clothes, rags, torn bags, and makeshift suitcases littered the ground. A hundred feet away was a pop-up building housing both a small branch of Sant Ambroeus, one of the most expensive and elegant coffee shops in Milan, and an “officina” tied into Expo 2015, promoting trade and tourism in China as well as Beijing’s bid for the 2022 Winter Olympic Games. The juxtaposition of poverty and wealth, migration and globalization, brought together key themes of this book.

This mixture constituted a refrain in a narrative I encountered days earlier in Marseille, a tourist destination and port of debarkation for immigrants from Tunisia and Algeria. I am not referring to the sight of homeless people sleeping in doorways of comfortable neighborhoods that has become a commonplace of urban living around the world. Rather, I allude to markers of long journeys taken by those with little or no choice: garbage piles with abandoned toys; empty, used-up suitcases crawling with bugs; woven and taped bundles; scraps of clothes that are unfit for the climate. In this volume, Susan Harbage Page and Inés Valdez label such refuse as “residues of border control.” These traces of border control appear, as well, in major airports such as Chicago O’Hare and out-of-the-way ports such as Yangon (Burma). I am struck by the way these borders are marked by a plethora of “no entry” or “entry forbidden” notices, which outnumber welcome signs. Border protection is also signaled by disposable plastic gloves increasingly donned by workers who come into contact with migrants, so that “a political border is the near-totemic site of inoculation from (unwanted) others outside the nation” (Cox 2014, 45). Yet because national frontiers are also sites for global commerce, these environs remain in close proximity to glittering shops, expensive restaurants, and well-to-do business people.

The contrast between those who benefit from global mobility and those who are disadvantaged by it has become a cliché. Counter-narratives do exist, however. We find them in pockets of resistance—organizations such as La Cimade1 in France—which work with migrants on social justice projects and creative forms of expression. Such creations and heritage materials, particularly those found in museums and archives, are the central focus of this book. Some are prominently located, such as the Ellis Island site in New York’s harbor. Spanning the globe, this book also includes communities that rarely appear in global cultural or political narratives, such as Cambodians in Australia, Macedonians in Canada, and Shanghai Jews. Some of the institutions devoted to these populations are tucked away. For example, a few blocks from the migrants in the square in Milan, set into the side of the station, is a new Holocaust memorial dedicated to the Jews and dissidents who were shipped from there to German concentration camps in the Second World War. I would never have known about the Shoah Memorial of Milan if I had not been told by my peers at Politecnico di Milano; when I asked staff at the railways and tourist office at the station, none of them were aware of it, even though it has existed since 2013.

p.3

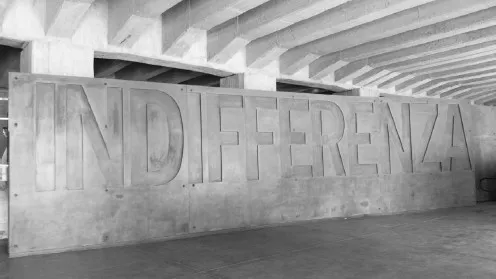

Binario 21 (or track 21), the site of the memorial, is a dark, underground platform built for non-passenger trains.Visitors are met with a gray concrete wall engraved in tall letters with the word Indifferenza (indifference). This grim reminder that the results of a failure to notice or act can be as fatal as calculated aggression leads into the exhibition. Video screens and signage tell the story of Milan’s Jews and their deportation, listing names and noting staggering statistics, such as the fact that only twenty-two people arrived alive from one 1944 transport of 605 human beings. A metal funnel shaped like a smokestack contains a somber space for reflection. But the most effective part of the site is the livestock cars sitting on the track as if awaiting human cargo. The wooden railway carriages are rendered even more eerie as trains pass overhead, rattling the tracks they sit on, yielding the impression that they are still used instead of ghastly containers for memories of misery. The poorly lit cars hold wreaths. At the end of the track is a sign forbidding people to go any further, its message now symbolic.

The silence and emptiness of Binario 21 alone would be an effective testament to the horrors of deportation as a form of coerced migration. But the space acquired new resonances in July 2015. The site’s organizers and sponsors enacted their commitment to oppose indifference by turning the coatroom area into a shelter for thirty migrants from Ethiopia and Eritrea each night. Migrants slept on cots, washing themselves and their clothes in the visitor toilets, which now hold showers (Herenstein 2015). Meals were provided as well. Rossella Tercatin (2015) describes the ways in which cultures intertwined at the site: “It’s not every day that Muslims break their Ramadan fast with a kosher meal delivered by a Chabad-Lubavitch soup kitchen. But for Adil Rabhi, who has partaken of the certified kosher pasta and snacks for the past week, it’s becoming the norm.” A Catholic community, Sant’Egidio, which partnered with the memorial since its founding, provided volunteers. The space, a transitional site in the 1940s and again seventy-five years later, offered safety and comfort to individuals who awaited a resolution to the impasse at Italy’s borders as other European nations refused to take some of the 55,000 Africans who crossed into Italy in the first months of 2015 (Tercatin 2015).

p.4

The Shoah Memorial of Milan is a unique example of an exhibitionary institution’s involvement in the story of human migration. However, other institutions around the globe are dedicating (or re-dedicating) themselves to the stories of new immigrants as well as to recounting narratives of historical migrations. For many sites, this is part of an effort to acknowledge and include the role of diversity in national history, and in some cases, the political motive supersedes the cultural or social mission of the presentation. One goal of this book is to offer readers relevant theory as well as a broad array of examples of such sites in order to foster the creation, examination, and discussion of museums dedicated to population movements. The articles inside this volume offer insights drawn from multiple disciplines, among them, museum studies, history, sociology, anthropology, psychology, archaeology, art history, rhetoric, political science, and education. The chapters meld theory about immigration with feminist studies, multiculturalism, and the construction of memory, and they address the impact of new technologies on the representation of migration, exile, and diaspora, not only in museums but also in archives. And finally, they provide a truly global scope, taking visitors from Shanghai to Elmina in Ghana, from the Polish Museum of America in Chicago to the new Emigration Museum in Gdynia, Poland. Many of the institutions are linked to colonial history, either because they focus on new immigrants from former colonies or, in a few cases, because they share the history of colonizers who were repatriated after independence.

The book is not designed merely for academics or professionals working in archives or museums. Individual chapters express diverse perspectives, including the voices of artists, visitors, undocumented immigrants, and other members of source communities. The intention is to assist institutions (and possibly the governments that run them) in welcoming migrants and encouraging the mainstream population to accept them. The authors and I strove to present abstract theories in terms that general readers would understand in the hope of promoting the cause of refugees, immigrants, and asylum seekers around the world.

In 2006, UNESCO published the results of its international meeting on migration museums (Italian National Commission for UNESCO). Institutions at the meeting primarily represented European nations, with participation from Brazil, Australia, and Israel. Other nations did not contribute but expressed interest. According to the final report, the meeting’s purpose was “to exchange information on the role of migration museums in promoting migrant integration policies and cultural diversity.” The report emphasized the importance of cross-cultural knowledge and exchange in the efforts of archives and museums to increase the inclusion of racial and ethnic minority populations. It also studied the conflicts inherent in such work: for example, whether assimilation, integration, cohesion, or another model is ideal; whether to focus on origins or destinations. Most of all, the meeting and its ensuing report demonstrated the salience and significance of cultural institutions in working with populations that have experienced forced or willing migration. A purpose of this book is to contribute to that effort by rendering a collection of thought-provoking and sometimes controversial texts available to a wider public.

p.5

Several chapters take provocative perspectives: for example, Helen Light argues against the creation of multiple small museums dedicated to individual populations. Robin Ostow analyzes the 2010–2011 occupation of the French National Museum of Immigration by undocumented migrants, situating it within the history of workers’ rights. Other essays explore the ironies of a postcolonial world: sites of oppression that have become stations in tourists’ ritual journeys celebrating liberation; a museum dedicated to pieds-noirs, descendants of the French who colonized Algeria and who are now disparaged as a conservative political force; an archive related to expatriates working for international businesses. Unlike similar works, this book embraces the contributions of archives as institutions that join museums in collecting the art and material culture of communities. It examines the differences between institutions at points of origin and those at destinations, and it will explicitly emphasize particular groups among migrants and immigrants: refugees, exiles, asylum seekers, and diasporic populations. Global Mobilities will thus offer a comprehensive overview of the field for those interested in understanding its complexities.

Mapping the research: borders and contours

The growing literature on museums and communities, and in particular on museums’ relationships to ethnic and racial minorities, features works on asylum seekers, exiles, displaced persons, and other migrants. These populations are not the primary focus of edited volumes such as Viv Golding and Wayne Modest’s Museums and Communities: Curators, Collections and Collaborators (2013); Sheila Watson’s Museums and Their Communities (2007); and Ivan Karp et al.’s Museum Frictions: Public Cultures/Global Transformations (2006). Nevertheless, these works contain valuable contributions that are cited by authors in this book. Museums and Source Communities: A Routledge Reader (2003), edited by Laura Peers and Alison Brown, is a closer analogue, yet one of its most useful angles is the focus on indigenous populations.

p.6

Other helpful works with themes close to this collection restrict themselves to particular geographic areas. Museums, the Media and Refugees: Stories of Crisis, Control, and Compassion (2008), edited by Katherine Goodnow, Jack Lohman, and Philip Marfleet, discusses only institutions in London (Philip Marfleet’s article from this book is reprinted herein). Together with Hanne-Louise Skartveit, Goodnow also edited Changes in Museum Practice: New Media, Refugees and Participation (2010), which addresses especially the ways in which “serious” digital games may educate others about refugees’ experiences. Books such as Erica Rand’s The Ellis Island Snow Globe (2005) have concentrated on individual institutions devoted to immigration, with Ellis Island being the most popular institution featured. Diaspora and Visual Culture: Representing Africans and Jews (1999), edited by Nicholas Mirzoeff, limits itself to two scattered populations, both of which are represented in this volume as well.

As recently as 2011, Grosfoguel, Le Bot, and Poli commented on the paucity of research on migration and museums (2011b). At the time of writing (2016), there is no shortage of research on migration in European institutions, thanks largely to two European Union-funded projects—Eunamus and MeLa. Eunamus, which was funded from 2010 to 2013, focused on “European National Museums: Identity Politics, the Uses of the Past and the European Citizen.” Even though the project did not explicitly focus on migrants, the emphasis on identities and citizenship led to studies related to migrants. The project yielded National Museums: New Studies from Around the World, edited by Simon Knell et al. (2011), which includes areas beyond Europe. Museums and Migration: History, Memory and Politics, edited by Laurence Gouriévidis (2014), also primarily emphasizes European institutions. Its strengths include theorizing on the imbrications of history and politics. Two more recent works derive from the MeLa Project: Museums, Migration and Identity in Europe: Peoples, Places and Identities (2015), edited by Christopher Whitehead, Katherine Lloyd, et al., and Migrating Heritage: Experiences of Cultural Networks and Cultural Dialogue in Europe (2014), edited by Perla Innocenti. The MeLa Project, which will be discussed in greater depth in Chapter 2, ran from 2011 to 2015 and used interdisciplinary approaches to consider the role of migration in relation to European museums. All of these books are essential underpinnings to this volume.

Whitehead’s work derives from a complex understanding of place as a dynamic force, through which “migration and related issues such as ideas of belonging, disadvantage and prejudice can be presented as historicized phenomena that involve antagonisms to be faced in the present. At the same time, the repositioning of place means that the inevitable political agency of the museum can be both problematized and reflexively mobilized to engage with socio-political debates, tensions and possibilities” (7). The value of this approach is especially evident in two chapters which compare presentations of Turkish identity in exhibitions in Turkey and other parts of Europe.

p.7

Innocenti’s book is based on a dual perspective on “migrating heritage”—heritage as it migrates with population movements and as it travels through digital networks. It bears particular relevance to Randi Marselis’s chapter on a digital project originating from the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam. Other recent works, such as Museum Communication and Social Media, edited by Kirsten Drotner and Kim Schrøder, and Ross Parry’s Museums in a Digital Age (2010), examine the role of new technologies in museums, but they are not predominantly preoccupied with media as it affects or empowers institutions devoted to asylum seekers, exiles, and other mobile populations, in the way that is found in Changes in Museum Practice: New Media, Refugees and Participation. Susana Bautista’s 2013 Museums in the Digital Age limits itself to US populations. Yet these books are important precursors, because several chapters in this book demonstrate applications of innovative technologies in museum work with new populations. Randi Marselis’s “Photo Seeks Family: Digitization, Visual Repatriation, and Performative Memory Work” offers an especially distinctive example.

Works on tourism also deal with issues addressed herein: for example, Joa...