1

Introduction

The time had arrived to return to Jerusalem, and reclaim the inheritance of their ancestors. All shared in this hope of speedy redemption, and a crowd of poor, simple-minded individuals resolved to start for Jerusalem … In less time than is required in Europe to get ready for a short excursion, a sizeable group of Falashas had started to go to Jerusalem …1

This group of Ethiopian Jews, which set off on foot for Jerusalem in the early 1860s, never reached their destination: the hoped-for miracle that aided Moses’ flight from Egypt, the parting of the Red Sea, failed to materialise. Many members of the group perished on the journey, others settled beyond the reach of the European Protestant Missionaries they were fleeing, Over one hundred years later, a miracle of a different kind assisted their descendants: in huge jumbo-jets sent by the state of Israel, they reached the promised land.

The Ethiopian Jews, otherwise known as Beta Israel, have long captured the Western imagination – ever since Jewish envoys, travelling in Ethiopia in the 1860s, brought back reports of ‘Black Jews’, apparently direct descendants of ancient Israelites, who retained a strict form of Biblical Judaism in the midst of ‘primitive’ Africans.2 In recent years, the Beta Israel made the headlines when the Israeli government conducted two airlifts into Israel, bringing six thousand seven hundred from Sudanese refugee camps in 1984, and another fourteen thousand from Addis Abeba, in only thirty-six hours, in May 1991.

The Ethiopian Jews soon found that Israel was not the Jerusalem of their dreams. Although their living standards soared and their children were educated – they felt that, as in Ethiopia, they were cast in the bottom strata of society. Their customs, the colour of their skin – even their Jewishness – were devalued in Israel. Like many other immigrant groups, the Ethiopian Jews of Israel feel they are losing control of their lives – and losing influence on their children who speak Hebrew while they speak only Amharic. In their bewilderment, they say that they are ‘becoming deaf’.

This book details the remarkable strategies that Ethiopian Jews have developed to cope with the difficulties of immigration and the psychological trauma of feeling disparaged in their homeland. They have recreated tight communal bonds, developed strong ethnic pride and reaffirmed their religious and cultural customs. They turn round the doubts cast on their Jewishness, insisting that they are the true Jews – glorying in a more authentic and purer religious tradition than other Israelis. In addition, they maintain faith in an ideal homeland of the future in which all Jews will be united in a colour-blind world of material plenty and Jewish purity.

Fieldwork

In December 1993, visiting Israel to find out whether it was feasible to conduct research amongst Ethiopian Jewish immigrants. I met academics,3 a number of Israelis working with Ethiopians,4 and Ethiopian Jewish community leaders.5 This last group introduced me to Ethiopian families, one of whom hosted me for ten days in Beersheva. The joy and exuberance of the Ethiopians I met and their warm welcome gave me both the courage and enthusiasm to proceed. Back in London, I studied Amharic with an Ethiopian student, and with help from the proofs of Dr Appleyard’s forthcoming book Colloquial Amharic.6 I learned the basics of the language.

I returned to Israel to start fieldwork in November 1994. I chose Afula Tse’era (‘Young Afula’), a newly-built neighbourhood of the small Northern town of Afula, home to one of the highest concentrations of Ethiopians in the country. In Afula, with a population of approximately 21,300 (1993 figures), five percent of households were Ethiopian, which given large Ethiopian family sizes, amounted to approximately a ten percent Ethiopian population7 – compared to approximately one percent nationally. In my immediate vicinity, nearly one household in five was Ethiopian (ninety-six out of five hundred).

As soon as I arrived in Afula. I sought an Ethiopian Israeli family to live with. On my first day, an Ethiopian community worker took me to the local Ethiopian elders’ club. With no warning, he put me in front of the group of men and told me to introduce myself – in Amharic. The men clapped their hands in delight at this white girl, who had come all the way from England, who knew no Hebrew but wanted to learn Amharic and the customs of the Ethiopian Jews. On my second day, I returned to the club, and the Israeli keep-fit instructor urged me to join the class. Foolishly, I agreed and ended doing jumping jacks with a group of Ethiopian elders! Luckily, the latter had the tact never to recall the incident – which totally contravened Ethiopian etiquette.

I sat on benches in the main street during the sociable hours in the late afternoon, and I attended the children’s after-school clubs, the women’s handicrafts class, and a few Hebrew classes. Soon, I received invitations to drink coffee in Ethiopian homes. In a country as strange to them as Israel, I was simply another strangeness.

Fantanesh became my first and best friend. She was, and still is, a popular, bubbly woman in her forties, short and plump with a very large tummy, her face nearly always smiling.

Fantanesh loved to tell visitors from other parts of the country, who marvelled at the presence of an Amharic-speaking White foreigner who ate injera (Ethiopian pancake), the story of how I settled in the neighbourhood: ‘Tanya arrived here and went to the classes. She spoke just a little Amharic, learned in England from an Ethiopian there called Yalew Kebede. I saw her sitting on the bench below and invited her in to drink tea. She brought bamba (a savoury snack) for the children. She came often afterwards. People said that I should not let her in my house like this because maybe she was a savaki [Fantanesh explained this term as someone who wants to change people into a different religion, like the Pentecostals]. But I said “No, she has come to study, to learn about our culture and our religion.”’

Fantanesh is at the centre of a small group of female neighbours. She is the one who tends to organise the local women to visit together a house of mourning, a woman who has given birth or a sick neighbour – calling out to them from the street. As I lived opposite her, I often heard the call, and joined in. I called Fantanesh ‘imaye’ (‘my mother’). She cared for me emotionally – listened to my tales of woe when I had problems with other Ethiopians, was unwell or homesick, counselled and comforted me, and fed me. Even though she spoke no English, from my first day in the field, she was always able to understand my imperfect Amharic, and conversely was able to make me understand anything she wanted, and often helped me to follow conversations.

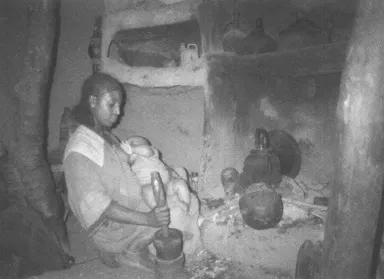

Grinding coffee. Che’era, Gondar, 1995.

Like Fantanesh, most Ethiopian Israelis understood rapidly the purpose of my study. In view of their abrupt change in environment, questions relating to cultural change, religious identity, and the experience of immigration, were daily concerns. Apart from anything else, they are fiercely proud of their cultural heritage and religious practices, and it was therefore unsurprising that I should want to learn from them.

Two weeks after my arrival in Afula, Abba Negusse, a tall old man, with an open, bright face, a missing tooth, and sharp eyes, invited me for coffee. As I walked in, in spite of his wife’s stern expression, I knew that I had reached my Ethiopian Israeli home. I sought the help of Fantanesh. She likes to repeat the story:

‘Tanya said to me one day: ‘I am looking for a place to live, here in your house would be so good but you have so many children and imita [grandmother], so you have no room. There at Abba Negusse’s they only have one daughter at home. Are they good people?’ ‘Yes’ I said. She asked me to ask them if she could live there because she was too afraid to ask herself. … Abba Negusse was happy to have her. After a while, her parents came, and they too stayed in Abba Negusse’s house and they came here for coffee. Her parents gave Abba Negusse a bedcover from England. Tanya gave me earrings and a head-scarf. She also went to Ethiopia and gave Mama Itaktu [a former neighbour] fifty Birr [approx. £10] and some coffee. She took a photo of her while she was grinding coffee!’

I lived for twenty months with Abba Negusse and his wife Mama Alefash. I paid them a modest rent, which significantly increased their monthly income, and I contributed to household expenses. I shared a room with their twenty-five year-old daughter Aveva and soon became a daughter of the house myself. This meant, much to my irritation at times, that I was expected to help daily with household chores and to entertain guests. I remember one day resting in my room, a rare moment of quiet and privacy after an intense forty-eight hour gathering of relatives. A guest came, I pretended not to notice, and stayed in my room – but I was called out to serve him tea. At other times, I was snatching a few moments to write up notes before the next event, when Mama Alefash would start cleaning and expect me to help. I often failed her in my duties, and my relationship with her suffered as a consequence. But to have been a proper Ethiopian daughter would have been a full time occupation.

In other ways, I failed to show Mama Alefash proper respect: injera (Ethiopian sour pancake), the staple food, was the problem. I sometimes accepted my neighbours’ offer of food, and returning home satiated, declined her offers. Other women were sensitive to this slight, and did not press injera on me when I said that ‘Mama Alefash has injera for me at home’. When my stomach resisted injera three times a day, I managed to avoid it altogether by telling my neighbours that I was eating at home, and Mama Alefash that I was eating at the neighbours. In fact, I sneaked a sandwich in town, or prepared hot food at home when the house was empty. On reflection, my hosts were probably aware of my ruse, but kept quiet, so as not to force me to blatantly defy Ethiopian etiquette – they understood the difficulties of a new environment, and the comforts provided by the food of one home’s country…

Abba Negusse became a veritable father, guiding me in my studies, attentive to my wellbeing, and, with great pride, taking me with him wherever he went whenever I wanted to join him. He rejoiced at my successes – in Amharic and in my learning of Ethiopian customs and etiquette – and berated me gently when I erred. One night, after a lively party, I sat on the street bench chatting and laughing with a couple of young Ethiopian male guests. Abba Negusse walked straight past, with no greeting, a clear mark of discontent: a daughter of his should not talk to men late at night. Mama Alefash and I never achieved such closeness, but we grew to respect each other and to live together in peace. Their daughter Aveva and I shared our joys and tribulations, until she left home after her wedding. A number of Abba Negusse’s other children, nieces, nephews and grandchildren became my companions, friends, and invaluable informants. In particular Telahun, one of Abba Negusse’s many grandchildren, who partly lived in our home – he had lived with his grandfather as a child, since his grandfather had no boys at home, his own children having left for Israel. Telahun was at this time an eighteen year-old boarding school student, and his weekends home were highlights of my time in Afula.

I spent my days with my neighbours: drinking coffee, chatting, visiting the sick, shopping, playing, attending funerals and celebrations. I was welcomed into their lives and homes, and within a year, t...