![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Introduction

EU climate and energy policy was once a matter of minor political importance on the EU agenda, with issues like the internal market, enlargement and monetary policies ranking far higher. After a decade of severe political conflicts and primarily symbolic policy outcomes in the 1990s, climate policy soared from ‘just another’ part of EU environmental policy to become a high-profile policy area in its own right. Especially from 2005 onwards, the pace of developments has been rapid indeed. By the end of that decade, a range of new and ambitious targets had been adopted, complemented by a broad palette of tangible and binding policies. Climate policy has emerged as a vital area of EU governance.

Ups and downs characterize the development of environmental policy, as noted by Anthony Downs already back in 1972 (Downs 1972). The ‘new drive’ in EU climate policy has been followed by financial crisis; as a result, issues of climate change and the related challenges are deemed less urgent, and have slipped further down on the political agenda.

This book discusses the central dynamics in the emergence and development of EU climate policy, and the driving forces behind it. Our overarching research question is: how can we best explain the development of EU climate policy development? We aim to shed new light on this, by taking into account both long-term historical developments and the impressive drive of recent years. What emerges is a fascinating story, not least of skilled entrepreneurs who have managed to create and exploit political windows of opportunity (see also Kingdon [1984] 2011). There are examples of more instant ‘carpe diem’ entrepreneurship as well as more persistent and long-term ‘tortoise’ entrepreneurship. This is also a story of institutional feedback processes. To capture this, we combine sociological New Institutionalism and political science theories in a novel way. Drawing on information from more than 60 interviewees, including both central actors and observers, we present stories never told before.

The book provides structured, comparative case studies of the emergence and development of four central climate sub-policies: the emissions trading system (ETS), renewables, carbon capture and storage (CCS), and energy policy for buildings. There are intriguing differences in the characters of these four. Whereas the ETS creates a basically harmonized European market for greenhouse gas permits, only indirectly inducing technology choices and development, the EU has involved itself rather directly in renewable energy and in CCS, aiming to transform industry in these areas. And the EU energy policy for buildings provides a framework for regulation of national building construction, giving member states significant leeway to determine specific technology standards. To capture the variation, we provide a new typology of differing EU climate policy outcomes.

European integration theory has prospered in recent decades, developing a rich body of literature that draws on a wide range of approaches. This offers a good foundation for understanding EU climate policy development. We develop an explanatory framework that relies primarily on three approaches to European integration: Liberal Intergovernmentalism (LI), Multi-level Governance (MLG) and New Institutionalism (NI). These perspectives can yield valuable insights, but none of them have been specifically developed to explain climate policy. Rather, they guide our conceptualization of the key mechanisms behind the development of climate policy. Here we seek to contribute to theory development in this field through the explicit formulation and empirical application of these mechanisms.

EU policymaking is a highly complex and multi-level venture, so it would be foolhardy to try to cover ‘everything’. Taking into account previous studies of EU climate policy (see the overview in Chapter 3), we have selected three main topics of theoretical interest and practical importance for special attention throughout the book:

• first, the role of industry, as a central stakeholder, target group, lobbyist and implementer of adopted policies;

• second, the role of policy interaction, since the ‘package’ concept has figured centrally in the new drive in EU climate policy and the European Commission (hereafter: Commission) has argued that EU climate policy now consists of well integrated sub-policies;

• third, the role of the EU-external environment, as many EU actors (the Commission not least) have long seen EU policy development as closely related to international climate negotiations and international energy prices.

On this backdrop we have made a deliberate selection of cases. We focus on cases characterized by varying likelihood that industry, policy interaction and the EU-external environment have played significant roles (see George and Bennett 2005, Gerring 2008). We base our assessments on extensive reviews of the documentation, as well as information and insights gained from over 60 interviewees. The combination of extensive empirical material, comparative case technique and active use of theory provides a good foundation for understanding how EU climate policy has developed thus far, as well as enabling some educated guesses about future policy developments. By no means is this book meant as the final say on the mechanisms that shape EU climate policy, and we invite fellow political scientists as well as EU policymakers to respond to our conclusions.

Capturing EU Climate Policy Variation: Steering Method and Competence Distribution

Climate policy has developed into a distinct and important policy area in the EU, but the character of its various sub-areas varies significantly. In order to understand how EU climate policy develops, we first need to capture this variation analytically. Scholarly discussions on policy conceptualizations have been central to the emergence of common and fruitful research programmes relating to welfare states, democracies, revolutions, and economic organization (see Hall and Soskice 2001, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer 2003). Shared conceptualizations can hinder misunderstandings and misinterpretations, and enable researchers from different traditions to trace patterns of commonalities and variation across a large number of cases – in turn, fostering fruitful scientific discussion.

EU policy discussions often centre on to two dimensions: the Steering Method and the Competence Distribution (see Wallace and Wallace 2006, Young 2006). Most actors involved in climate policy debates agree that low-carbon technologies and industry practices will have to become more profitable, and that new and better technologies and technical practices are needed (Metz et al. 2007). However, they do not agree on how to achieve this, or the steering methods. Some favour market measures that put a price on carbon emissions or in other ways may indirectly induce technology development, whereas others favour technology development measures focused more directly on ensuring that industry will develop and make use of specific technologies.

Market measures either create new markets or alter existing ones. They may put a price on polluting activities (as with emissions trading) or reduce the price/generate an extra income on low-carbon activities (like green certificate markets) or bring new information into price-forming processes (like quality labels and certificates). The rationale is that the regulated industries will develop low-carbon practices once this is economically viable (Sims et al. 2007: 306). The prime task of governments and/or the EU is then to design markets that can make it economically beneficial to produce and use low-carbon products. Market measures do not in principle favour any specific industries or technologies, but allow the market forces to choose winner industries and technologies. The precise economic incentives will not be set by the EU or the governments, but are to be shaped by the market.

In contrast, technology development steering may involve technological standards (such as building codes), technology-specific governmental support (such as feed-in schemes) or governmental investments in certain technologies. It is assumed that low-carbon technologies and practices will diffuse once the technologies are mature and technology competencies have become widely disseminated. The prime task of governments and/or the EU is then to develop technology standards, and to finance R&D, demonstration project and training activities. Governments are advised to apply a wide range of measures, adjusted to the specific needs of different industries and the various low-carbon products that are under development (Sims et al. 2007: 306).

The second dimension, the Competence Distribution, goes to the core of European integration theory, and has been described by Haas as ‘the shift of loyalties, expectations and political activities toward a new centre, whose institutions possess or demand jurisdiction over the pre-existing national states’ (Haas [1958] 2004: 16). This broad definition encompasses both cultural and structural centralization, and the increased number of EU policies and EU member states. We will focus more specifically on the distribution of authority within our selected climate-policy areas. A key point here is whether it is the member states or the EU organizations that are given the basic competence to govern the policy issue in question (Olsen 2007: 96).

Scholars have employed a range of terms to characterize this kind of centralization of power within the EU. For instance, Schimmelfenning and Rittberger (2006: 74–75) use the term ‘vertical integration’ in describing the distribution of competencies between EU organizations and member states. The more power that EU organizations are given to govern ‘joint decision-making, implementation and enforcement’, the stronger will be the degree of centralization (Moravcsik 1993: 479). This relates in particular to issues such as whether the EU or national governments have competence to change basic features of the policy, for instance by developing detailed regulations; and issues of monitoring of progress and implementation in the policy area. EU organizations can be seen as stronger if they do this directly, than if they rely on information supplied by member states, and have competence to ensure enforcement by use of coercive measures, like formal infringement cases and fines.

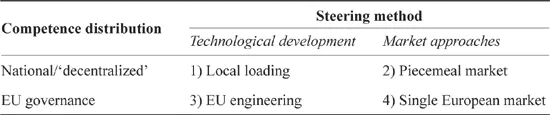

Often, policies will not be clear-cut, and may contain differing elements. Still, we believe that it will normally be possible to identify which steering method and competence distribution dominates a certain policy outcome. Combinations of the two dimensions create the four categories presented in the two-by-two table, Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Four types of EU climate policies

‘Local Loading’ EU policies can be seen as giving member states the upper hand, and encouraging the use of national technology development instruments, ranging from state aid schemes directed at promoting specific technologies, to emission limits and other governmental regulations. Also what we refer to as ‘Piecemeal Market’ policies give member states most of the competence to develop policies, while encouraging the use of national market instruments. Hence, here we will find market change at the national level, but no European harmonization of markets. What we call ‘EU Engineering’ policies give EU competence to engage directly in promoting specific technologies, whether through technological requirements or funding of specific technologies. Finally, ‘Single European Market’ policies give the EU the upper hand in the creation, surveillance and control of EU-wide market measures. This latter outcome is often characterized as ‘harmonized EU policy’ and has been in focus among scholars of European integration. Neither climate policy stakeholders nor analysts agree on whether this policy outcome is the best way towards a low-carbon society, however.

We will pay special attention to how Single European Market outcomes are created, but we do not see this outcome as normatively superior – such judgements are left to the reader. In the following, we present the theory basis for each of our three theory topics.

Exploring the Role of Industry: Simple Braking Block – or More Multi-faceted Player?

Media accounts and empirical assessments of Brussels climate-policy processes tend to attribute considerable power and influence to industry lobbyists. For instance the scholarly accounts of the failed efforts of establishing a carbon tax in the 1990s highlight the braking block role played by industry (Skjærseth 1994, Ikwue and Skea 1994). Other pieces of evidence point in different directions, for instance highlighting the role of big oil companies as emissions trading frontrunners and inspiration sources for the subsequent EU policy development (see Christiansen and Wettestad 2003, Victor and House 2006). What role does industry play for the emergence and development of EU climate policy – is it a simple braking block, easily analytically captured? Or is it a far more multi-faceted player, with differing roles in differing phases and issues? Can mechanisms derived from the theory perspectives help us to pin down the actual role played by industry?

The three perspectives provide different propositions in this respect. Liberal Intergovernmentalists (LIs) posit that national governments will act as instruments for economically dominant national industries (Moravcsik 1993, 1998). New Institutionalists (NIs) highlight the mutual interdependence between industry and governments, and the common culture and institutional features they have developed over time (Olsen 2007, Fligstein 2008). Multi-level Governance (MLG) scholars argue that shrewd Brussels entrepreneurs able to create multi-level networks (spanning national and EU levels of policymaking) will be the most influential (Coen 1998, Mazey and Richardson 2006, Marks, Hooghe and Blank 1996). We will explore whether the three perspectives in conjunction are able to grasp the most important mechanisms through which industry affects EU climate policy, and will then develop some proposals for analytical improvements.

The historical process-tracing of the empirical studies enables us to follow and discuss the long-term consequences of industry influence, not only the more temporary effects. The four climate policy cases target industries with varying business practices, differing Brussels presence, and varying degrees of transnationalization. Further, included in the sample are two cases where earlier studies have indicated that industry played a major role: the ETS and Renewables; as well as two cases where industry seems to have been less active: CCS and Buildings (Skjærseth and Wettestad 2008, Boasson 2011). On this backdrop we will discuss whether traditional European integration approaches can provide appropriate conceptualizations of the impact of industry impact. Further we will probe into whether there is any clear relationship between the character of the industries involved in policymaking and the four types of climate policy outcomes.

Exploring the Role of Policy Interaction: Actual Mingling and Cross-fertilization – or ‘Isolated Icebergs’?

Different EU policies may affect each other. The first wave of European integration theory, neofunctionalism, attributed considerable explanatory power to policy interaction, or spillover, which was the term used by Ernst B. Haas ([1958] 2004). Haas was particularly interested in interaction over time, and predicted that issue-areas in which the EU gained considerable competence would increasingly affect other policy areas. International environmental politics scholars have paid increasing attention to interaction, and conclude that the EU’s various environmental policies have significant impact on each other (cf. Oberthür and Gehring 2006). In contrast, recent studies of EU administration have found fairly little communication across sectors or policy-areas (Egeberg 2006a, Trondal 2010).

What role, then, has policy interaction played in the emergence and development of EU climate policy? Has ‘mingling’ and cross-fertilization between policies led to radically different policy outcomes? Or will closer examination show that policies have developed primarily due to issue-internal factors, as ‘isolated icebergs’? Can mechanisms derived from our theory perspectives help us in pinning down the actual role of policy interaction?

In LI, particular attention is paid to how different policies may be interlinked through bargained deals (Moravcsik 1998). This happens because national officials try to link issues in a way that enhance their clout. That perspective will also make it natural to expect that policies may have functional and economic consequences, such as market changes, for other policy areas. By contrast, the NI approach focuses on how the policy recipe, norms, practices or worldviews that underpin one policy may contribute to shape other policies (see Fligstein and Stone Sweet 2002). And thirdly, although the MLG approach does not discuss interaction very explicitly, it is in line with the thinking of this perspective to expect EU officials to initiate linkages between policy areas.

We will conduct long-term process tracing in order to identify when interaction occurs and how it affects policymaking over time. As noted, we have two cases where previous research indicates that interaction played a major role for the policy outcome (CCS and energy policy for buildings), and two where issue-internal dynamics might have been more important (the ETS, and renewables) (see Claes and Frisvold 2009, Wettestad, Eikeland and Nilsson 2012). Can existing theories of European integration capture the major policy interaction effects? And is there a relation between policy interaction and the type of climate policy outcome?

Exploring the Role of the External Environment: Binding Hands – or Handy Opportunities?

Climate change has become an important issue in international politics. This is indeed a policy area in which EU policymaking is clearly linked to EU-external factors, and in particular the rules, practices and negotiations of the global climate regime (see Oberthür 2006, Skjærseth and Wettestad 2008, Wettestad 2009c). Also relevant are the global and regional energy situation and international market developments for various energy sources and technologies (Jordan and Rayner 2010). Thus we need to explore how factors external to the EU have played into policymaking (Lenschow 2006: 425).

What role has the external environment played for the emergence and development of EU climate policy? Have such concerns bound the hands of EU policymakers, giving them scant leeway in the policy development process? Or have developments in the external environment primarily created convenient opportunities for creative policy entrepreneurs who have used the international backdrop to promote their own ideas and interests? How can mechanisms derived from our perspectives help us identify the actual role of the EU-external environment?

Although most EU policies have an external policy dimension, such EU-external factors have not been much discussed in European integration studies (Jørgensen 2006: 511). Instead, the Euro...