- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book takes a radical look at organizational crime and deviance through the prism of Cultural Theory derived from anthropology. It does so through case studies and by introducing new concepts such as 'organizational perversion', 'tyranny' and 'organizational capture'. Exploring the effects of change and environmental influences such as globalization, new technologies and trade-cycles on the nature and potency of criminogenic communities such as ports and holiday resorts, the book gives special attention to the justification of ethics and to the analysis of behaviours that have contributed to the current economic downturn. The Appendix offers a practical guide to the ethnographic assessment of links between organizations and varying types of crime and deviancy using a Cultural Theory framework.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Locating Deviance by Gerald Mars in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Basics of Cultural Theory

There is nothing so practical as a good theory.

Kurt Lewin

Finding a Theory

There have been numerous definitions and approaches to ‘culture’, with one commentator recording over 300 variations. This is because the ‘Holy Grail’ for social scientists and philosophers has long been to find a key by which they might define, classify and compare typical behaviours and values that would be applicable to all mankind. Numerous proposals as to how this might be achieved have been offered, some seemingly more successful than others, but none has proved fully practical – that is, applicable to the whole range of world cultures and able to offer sustainable comparisons. They failed because they didn’t meet the two vital conditions for effective classification: their categories proved to be neither exclusive nor exhaustive. This meant they were always liable to be torpedoed: someone could always say, ‘Your categories and comparisons don’t apply to the people I studied’ – a response that has been called ‘spiteful ethnography’ (Geertz 1967). These earlier attempts at classification may have fitted – but, to adapt Christian Dior’s metaphor, ‘They fitted like a poorly made frock fits – they fitted where they touched’

It was while searching for a way of classifying occupations and their deviance that I became involved in this larger anthropological problem. Each attempt to classify workplace deviance by applying the usual occupational taxonomies – blue collar/white collar; lower-, middle- and upper class – had proved inadequate. Anthropologists, in facing their similar problem, had accumulated considerable data on a wide variety of cultures – just as I had extensive data on how fiddles were organized in many different occupations. But in neither case could differences be accommodated in a viable system of classification.

At this time, Mary Douglas was promulgating her system for classifying cultures. She produced a taxonomy that not only applied to so-called ‘primitive’ societies but was, she insisted, relevant to all societies and at all times. She called her taxonomy Grid/Group Theory; it later came to be known as Cultural Theory and is referred to here as CT. Now it was possible to effectively compare Hottentots with, say, Bushmen, Australian Aborigines with Western society professionals, and medieval bankers with their current counterparts. And it was to prove similarly effective as a basis of classification when I applied it in other social contexts and, as here, to occupations, organizations, and their different types of deviance.

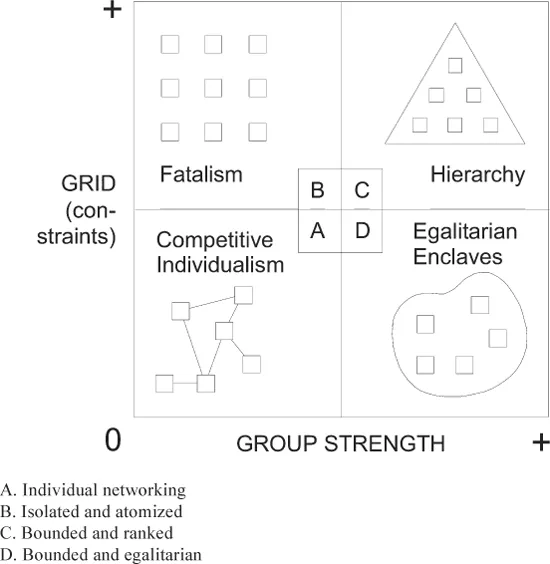

The core of Douglas’s method was to choose not a single basis of comparison but a duality. Scouring the literature on (so-called) primitive societies,1 she examined how they were structured according to two criteria2 and developed further in 1978 to demonstrate how they could be universally applied.3 The first asks how far is a society able to impose rules and constraints on its individuals, thus limiting their choices. She called this ‘Grid’. Therefore a society with many rules and constraints – such as the caste societies of India – would be rated ‘strong’ on Grid. At the other extreme, societies that allow members many choices – as with, say, Californian swingers – would be rated ‘weak’ on Grid.

The second dimension measures the strength of incorporation within groups. This she called ‘Group’. A Chinese lineage offering full life support to its members would measure ‘strong’ on the Group scale – so too would an army platoon or the staff of an oil rig where residence, leisure, common interests and identity similarly overlap. In contrast, New Guinea Highlanders, the British Columbian Kwakiutl and, especially in the West, independent entrepreneurs, for all of whom no one group is all encompassing, would measure ‘weak’ on the Group scale.

By considering these two dimensions as continua – as ranging from ‘strong’ to ‘weak’ – and then by placing them on a 2×2 matrix, Douglas illustrated four archetypal ways of organizing – four ways that relationships are manifest ‘on the ground’: ‘weak grid and weak group’, ‘strong grid and weak group’, ‘strong grid and strong group’, and finally, ‘weak grid and strong group’.

The relative strength of Grid can be assessed by the use of space, time, objects, resources, labour and information. Taken together, they determine the strength of autonomy, insulation, reciprocity and competition. An individual’s autonomy in a specific milieu – how far they are allowed to carry out tasks in ways defined by them – is a good indication of Grid. Low autonomy is found where constraining rules are strong; high autonomy, where they are weak.

Figure 1.1 The four characteristic ways relationships are manifest ‘on the ground’

Source: Frosdick and Mars 1997, p. 110.

The insulation of people from others is also a feature of Grid. A ranking system, for instance, insulates people: it separates them from others and therefore contributes to strong grid. The absence of insulation, on the other hand, readily permits links between people and contributes to low grid. Reciprocity, the third indication of Grid, has to do with how much a job allows its incumbents to offer others and how much they can accept in return. Strongly gridded petty criminals can offer very little to anyone, whereas weakly gridded gang leaders can offer a lot. Competition is the final indicator of Grid. A job with few constraints indicates weak grid that facilitates strong competition – social positions are ‘up for grabs’, whereas high constraints inhibit competition.

Aspects of Group are assessed by the frequency and mutuality of contact, the scope of activities under the aegis of the group, and the strength of its boundary. Repeated face-to-face contacts with the same people indicate that both frequency and mutuality are strong. Group strength increases further as the scope of group activities extends. Sharing a common residence, working and taking recreation together, as, for instance, with terrorist cells, or army platoons, all increase group strength.

The strength of a group’s boundary is indicated by its members’ perception of the distinctiveness of its internal behaviours compared to those considered appropriate to outsiders. Another indicator of the strength of boundary is the ease or difficulty of entry. The more difficult to enter, the stronger the group. Elaborate recruitment procedures thus indicate strong Group. These components of Grid and Group have been codified under the acronym ‘LISTOR/SPARCK’ and are arranged as a ‘do-it-yourself’ guide to categorizing relationships in organizations – see the Appendix.

Douglas’s next step was to return to the anthropological literature and reexamine these four archetypal ways of organizing from the standpoint of their social values and attitudes – which incorporates their ethical systems. These she found also fell into four distinct clusters, each correlating with one of the archetypes – that is, she found the way people were organized according to their grid and group ratings was congruent with their values, attitudes and appropriate ethical systems – and these justified their characteristically different behaviours. Cultural Theorists refer to these as ‘the four solidarities’ or ‘the four ways of life’ terming them as follows: Individualism (weak grid and weak group); Fatalism (strong grid and weak group); Hierarchy (strong grid and strong group); and Egalitarianism (weak grid and strong group). These are marked A, B, C and D respectively in Figure 1.1.

All societies comprise features of all the solidarities since they are the basic institutional forms to be found in any period, in any part of the globe, at the smallest and the largest of scales, and with different degrees of strength.4 It is worth emphasizing that though all solidarities in a society are evident in different degrees, an overall ‘cultural bias’ will emerge that emphasizes the competitive dominance of one or sometimes two (and occasionally three) solidarities at any one time.

When I applied this approach to occupations and their everyday deviance in ‘everyday jobs’ (see Chapter 3) I found the same basic correlates – that the way a job was organized in grid/group terms was also directly associated with their incumbents’ values, attitudes and behaviours, and that these invariably involved deviant practices and the ethical justifications sustaining them. Such behaviours had little to do with the psychological make-up of individual participants, being instead based on their social situation – this makes CT a sociological, not a psychological, theory.

Now to look in greater detail at the general characteristics of the four archetypal solidarities, each of which. as will be apparent, presents a distinct, strongly cohesive, and coherent worldview.

Hierarchy

Hierarchy is characterized by strong grid constraints and strong encompassing groups. It is one of the dominant forms of social organization found in societies with simple technologies. In the West, Hierarchy is one of the two most influential cultures (the other being Individualism). Applied to organizations, these are termed ‘bureaucracies’.

A classic example of Hierarchy is the Hindu caste system. Being strong on grid constraints involving ranking and conformity to rules and strong too on the group dimension emphasizing incorporation, most Hindus have relatively little choice (certainly when compared with most Westerners) over where they live, what they can eat, the jobs they can do, or who they may marry. Their strong groupings are able to maintain and sustain these constraints.

Hierarchies are structured as pyramids marked by divisions of labour, ranking, and differential rewards. In the West, whether a bureaucracy is criminal or legitimate, it similarly subjects its members to rules, reveals ranking with differential rewards, and is able to offers its members a sense of common identity.

Members of Hierarchies, deferring to rank and office, respect authority to those assigned it and give priority to rituals and ceremonials that sustain and justify the group. Their members operate with long time-spans – since groups last longer than individuals – and they consistently use the past to justify behaviours in the present. They tend to defend relatively harsh punishments5 and are prepared to sacrifice individuals for infractions of the group’s moral code since these are seen as threatening the effectiveness and sustainability of the group. In Hierarchies, the interests of individuals are essentially subordinate to the interests of the group.

Hierarchies are marked by a concern with regulation and order that is represented and maintained by those concerned to sustain their structures and processes, particularly their elites, and by those who function to enforce its rules. In the West, these values dominate during economic downturns when arguments for regulation are listened to and effect policies (see Chapter 9) that modify the excesses of anarchic Individualism manifest in the previous upturn.

In less technologically complex societies, divisions of labour may largely be limited to gender differences and leadership roles. Within Western society, organizations with more intense divisions of labour, rank, leadership and authority derive from office and the knowledge of validated experts who rely on orthodox precedents and traditions as their charters for action.

Boundaries – whether spatial (Mars 2008), social or conceptual – are strongly affirmed in Hierarchies. These not only mark distinctions of rank but define insiders and outsiders and offer barriers to entry at different levels. This applies also to information that is validated only when it flows via accepted conduits. In situations of change, this can sometimes prove unadaptive and dysfunctional.6

Because their elites centrally control resources, Hierarchies can ‘tax’ and reallocate them to celebrate rituals and ceremonials – such as anniversaries – that repetitively glorify and bond the group and allow them to further buttress their own institutionalized positions. In Western bureaucracies, they may use them to carry out research for the same ends.

Hierarchic strength derives from its emphasis on tried and established procedures and the security and rewards this offers members. In return, they are offered support and a ‘closure of ranks’ if this is necessary in adverse involvements with the outside. As might be expected, if criminality is involved, these characteristics are at their most pronounced. But since Hierarchy is dependent on its lowerarchy’s resolute sense of group identity, this can be maintained only as long as an elite can justify to the lowerarchy why it should enjoy an unequal allocation of resources.

Managers will readily recognize the high-grid/high-group structure as appropriate to many organizations and as particularly typical of old established and single-product companies, especially where their functions or products remain relatively consistent – as, for instance, in established banks and insurance companies, especially those run by family dynasties,7 and government departments, both of which typically make obeisance to their pasts by displaying portraits of past chief executives in their boardrooms. Hierarchic occupations are well represented in accounting departments of head offices, in certain medical specialties, and in the military. It is similarly the defining feature of organized crime groupings, as discussed in Chapter 2. But these defining features may be overturned when an organization is subject to ‘organizational capture’ by aberrant individualists, as discussed in Chapter 7.

A common feature of organizations is the built-in conflict (or at least tension) that exists between departments with a hierarchic bias (eg. accounts) and those with an individualist one (eg. sales). The Hierarchy, respecting caution, precedent and risk aversion, will invariably be opposed to the short-termist, more risk-prone innovations and practices carried out or proposed by their individualist actors. And this often surfaces when risk-prone individualists engage in rule bending, as they are prone to do.

Individualism

Individualism, defined by weak grid constraints and weak group involvement, is not readily subject to rules, constraints or ranking, and its principle social mode i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Preface: A Personal Journey, a Guide to the Book, Chapter Outlines

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Basics of Cultural Theory

- 2 A Cultural Theory Approach to Criminal Behaviours – with a Comment on the Characteristics and Vulnerabilities of Law Enforcers

- 3 Workplace Crime Including Sabotage – and its Wider Settings

- 4 The Egalitarian Enclave: Terrorism – A Positive Feedback Game

- 5 Hierarchy: Dock Pilferage – A Case Study of the Methods and Morals of Occupational Theft

- 6 Hierarchy: The East End Warehouse and a Note on Criminogenic Communities

- A Note on Chapters 7 and 8: Organizational Perversion

- 7 Individualism and Egalitarianism: ‘Organizational Capture’ and ‘Organizational Tyranny’

- 8 Individualism and Hierarchy: Management in Soviet Georgia – An Extreme Example of a Local Response to Distant Controls

- 9 Individualism versus Hierarchy: Kondriateff and his Crime Waves; the Behavioural Underpinnings of Booms and Slumps

- Appendix: A Practical Guide to Doing Organizational Ethnography: LISTOR/SPARCK

- Index