a The sustainable city

The ancient definition of a city, etymologically derived from the Latin civitas, suggests that the urban settlement should mainly be configured as an organization of human community, where the habitat, as well as the people, could retain the same importance and the same right of being part of the settlement itself. According to this idea, the city is a mixité of a number of structures, such as the land, the citizens, the activities, the infrastructures, the roads, the squares, and the parks. Even in literature, the idea of city is meant as a combination of human activities and physical infrastructures:

We do not…provide specific importance to the name of a city. All the metropolitan areas were built by irregularities, turn overs, drops, intermittences, collusions of things and events, and, in between, bottomless silence spots, by railways and virgin soils, by a great rhythmical beat and by the eternal disaccord and disarray of any rhythm; and as a whole it was similar to a re-boiling bladder set in a material container of houses, laws, regulations and historic traditions.

(Musil, 1957: 6)

Therefore, one can describe the city as a human ecosystem, part of the wider built landscape, and as such, can be “sectioned in the bio- and socio-diversity of the context.” If, instead, we consider the city and its built landscape as a mechanism, the landscape is “produced starting from the elements borrowed by other contexts” (Raffestein, 2003).

This model of the compact city can instead be described by numbering the various components, as outlined by Evans and Foord:

The notion of compact city…encompasses: 1. Social mix (income, housing tenure, demography, visitors, lifestyles); 2. Economic mix (activity, industry, scales from micro to large, consumption and production); 3. Physical land-use mix (planning use class, vertical and horizontal, amenity/open space); 4. Temporal mix of items from 1 to 3 (24 hour economy, shared use of premises/space – e.g. street markets, entertainment, live work). These urban environmental elements, that combine to determine the quality of life in higher-density, mixed use locations, can be triangulated in terms of the key features.

(Evans and Foord, 2007: 95–6)

The key features mentioned are physical, social and economic. Provided that no city can exist without its human heritage, the importance of its territorial boundaries and tangible built areas cannot be forgotten.

This chapter is meant to underline the importance of generating a new opportunity for the city. Rather than discussing the planning methodologies, or shaping design for the modern and old city, the imagination of various technological solutions can show, to both citizens and guests, how to interact with the existing structures and how to preview a different use of the city spaces. At the same time, it can create the chance of proposing various models for eventual new processes. These new processes cannot necessarily be identified with new constructions, new buildings, or new assets of the city. On the contrary, the idea supports the existing facilities with new use and new arrangements: only in this way, the real sustainable policies can be achieved. In fact, to avoid employing new materials, new energy provision and waste production can be considered as the only ecological means of facing the city question: this is the point of view of the environmental design response to the city strategy resolutions.

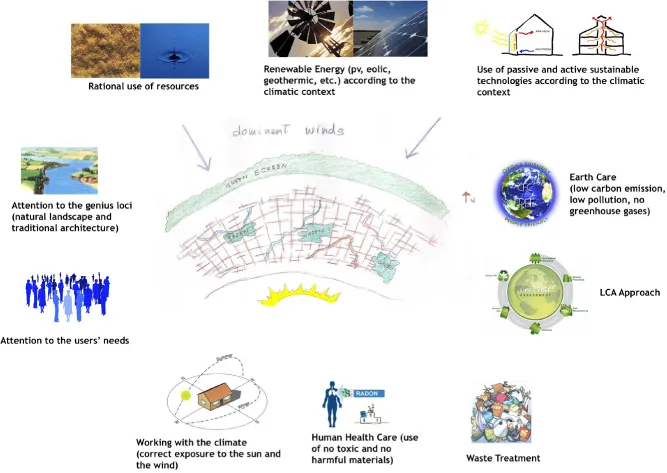

As far as the sustainable city is concerned, what is this chapter’s point of view? The most important parameters that a sustainable city should respect can be listed easily, while the parameters of how they could actually be applied and could be maintained in time are more complicated to understand. The list includes:

- rational use of resources

- employment of renewable energy (solar, wind, geothermal, etc.) according to the environmental context

- use of passive and active sustainable technologies according to the climatic context; attention to the “genius loci” (natural landscape and traditional architecture)

- earth care (low carbon emissions, low pollution, no greenhouse gasses, no ozone depleting emissions)

- attention to the users’ needs

- circular approach (using lifecycle assessment ex-ante methods and promoting the recycling and reusing of any activity products)

- working with the climate (exposure to sun and wind of activities)

- provision of green areas

- nearness to water supply (for drinking and other uses)

- connection to nonurban areas•human health care (use of non-toxic and harmless materials)

- waste treatment (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The sustainable city

The modes to achieve the completion of these parameters can be synthetized in three main actions: the decrease of resources, the minor possible constructions, and the reduction of waste. This means paying more attention to energy, material, and water, while proposing possible strategies and policies for any eventual transformation. The selection of design procedures should thus be in line with these principles and can be easily achieved through three main steps of city life: building, using, and rejecting. In each of these activities, the sustainability can be measured according to the amount of resources included. Instead of manufacturing a new concrete object, such as a building, a road, a square, or simply a bench for a park, the sustainable solutions for an ecological city could be the following:

- converting existing things

- modifying the energy consumption of the system

- reducing the nonvirtuous cycles

- reducing the amount of matter, energy and water needed for the transformation

- previewing a type of use for the new solution that would require low energy, less raw prime matter, less use of water, and less engagement

- attempting to reduce the unrecyclable or unrecoverable waste.

As it is known this is not the first time that such a policy has been advanced. Currently, for many institutions (the international agencies, the European Community, the local associations and committees) dedicated to saving the planet, the question of employment of resources is key, because even the survival of protected animal and vegetable species depends on that, and, of course, the preservation of human community.

Nonetheless, the tools that are useful for achieving these results have not become a real heritage for any professional or local authority making use of ecological and biocompatible instruments, both as methodologies and technologies. Scholars and land administrators have developed various approaches to resolve the city transformation question, with regard to the eco-cities, the sample-city, the mixed urban use, and the synergy-city.

They start from the fundamental concept that a different way of inhabiting this earth should be imprinted on the means of dialogue, shared choices and respect for users’ as well as the needs of the environment, and never on aggression, war, and prevarication neither to the individual nor to nature (see Ravetz, 2014).

This idea of de-growth,1 is not new: even the Chinese philosopher, Lao-tzu, in the sixth century bc, declared that we do not need big growth, but a great vision and simplicity. The more updated urban studies tackle the needs of de-growth, as the primary aim is not only the order and planning of the territory, but also of the urbe, which represents the blending of land and joining of citizens. As Bernardo Secchi (2014) states:

Usually, the debate on the de-growth … is right for the economists, as far as the increase over time of the rate is concerned, it is right for the sociologists, when its unbending or stopping explanations are interested…The planners should only acknowledge it, consider it, and consequently modify their design procedures, their idea of land and city.

This indicates that the city should be modified, re-arranged, regenerated, or even re-created without changing the amount of used material and energy. He is also optimistic regarding the possibility of applying this change into the modern city, when he hopes that “something is moving in this direction…due, on one hand, to the number of researches” that are currently based on these subjects, and on the other hand, to the fact that

more and more frequently designers are asked to study and process some visions. Visions rather than regulations, recognitions of meta-preferences, which…emerge from the whole of the researches … non final pictures, but paths, trajectories which explore the possible…new fictions which can provide a perspective of the contemporary society.

(Secchi, 2014: 313)

These visions can then be identified with simple solutions that will employ existing objects and parts of the city. At the same time, they could promote a strong and radical change in the life of people because the absence of construction and the presence of creativity and projectuality have properly substituted the aggressive speculations that had characterized the last century.

The sustainable city is one that does not promote any increase, any growth or any additional constructive activity, but rather only carries on its development, improvement and regeneration.

b The city regeneration question

Regeneration can actually be reconsidered as a method for reproviding comfort and livability to people inhabiting a town and to tourists as well as neighbors visiting these places. To “re-generate” means to give birth again to something, to provide to the existing reality a renewed life, new genes, new importance, and alliance with the earth.

Within this updated concept, there is the idea that this new life does not need to be created and delivered by employing a great amount of matter, energy, or water. No new resource is necessary, on the contrary, the existing sites, cities, and way of living could improve their vitality and appeal, without increasing the environmental load, both locally and globally. As Aimaro Isola declared when asked about the alliance with the earth of a design process or a landscape construction:

[It is] a very difficult alliance that with the earth…while designing, a colloquium begins and develops during which, slowly-slowly, we notice that the place reflects our face, we assume its faults and its virtues…Within the constraint of the built environment… [a number of] contradictions are hidden and co-living. We all would like…that in our works the violence would be sedate; so we could, by reflecting ourselves into the places, see a new happy face of ours.

(Isola, in Priori, 2012)

It became clear during this interview that it is the place itself that carries the potential of its transformation, improvement, and increase of quality. The regeneration of a place, which would be in alliance with the earth, should, in any case, not be violent or aggressive, but respectful of the natural existing elements.

How can this be possible, without low and soft interventions? Possibly with sustainable and respectful technologies or only a light reorganization and reuse of existing objects and townscapes?

A crucial aspect of the modern technological design is the difference between natural and artificial objects, which cannot actually be simply described in the twenty-first century as everything that is human-made, including the animals and the plants. Aimaro states:

Nature stays in front of us, not as a different other being, but supported by ineludibly rules, mathematical, geometrical, growing, of dissolution, of dissipation…and thus nothing remains to us than being wrecked, 2 softly, poetically, Leopardian? Or, on the contrary, do we actually make part of the nature, is it us and not only our body, but also our thought, our home, the landscape, the world? Therefore everything is nature, thus nothing is nature? Nature according to Spinoza: naturans, naturata?…where does nature end and where do we start? Or better, how do we succeed to conquer within a space of freedom? Space which could provide only the poem? But which could really open with the project a space to life?

(Isola, in Priori, 2012)

In these very suggestive sentences, Isola creates the space for design within the great realm of nature, without destroying the peculiar characteristics of nature itself. However, at the same time providing a number of important reasons for helping the natural landscape to host humans with their requirements, their life arrangements, personal qualities, and their “poetry.” An important item to be safeguarded by two actors of the architectural and technological process, the designers and the users. Both should try an alliance with nature, and both should neither deny nor neglect their poetry, to be closer and not further away from nature itself.

It is in the very city that the citizens and the designers meet and produce their vitality, their poems, and their suggestions. The softer the touch, the less detachment from nature there will be, both from the biotic and nonbiotic.

The city is made up with buildings, big squares, big parks, large streets…but all these important elements are also separated by small roads, little mews, and narrow paths. Narrow paths should be considered as an important part of the European and Mediterranean city, whereas larger streets are more common in the USA.

Therefore, regeneration should also become an opportunity for reflecting upon these minor realities rather than underlining the importance and relevance of the monumental and gorgeous pieces of the city.

c Methods of regeneration

The means adopted by this approach to regeneration are contained in a great number of literature essays, which assert the importance of reducing concrete interventions, while increasing reuse, recycling, and recovery of existing elements, from buildings to small trees.

In the last few years, various methods for regeneration have been processed and diffused. These methods pay “careful attention to the quality of the street-scape and to enhancing the network of small spaces and squares implicit in the historical layout” of the ancient cities, thus “…creating an attractive and popular place to live, work and socialize” (Thwaites et al., 2007).

A socially and sustainably correct method for sensitive architectural regeneration process of an old city would provide a number of positive characteristics and features, such as a “relationship with other city districts, exploitation of eventual waterside areas, vibrant social opportunities” (Thwaites et al., 2007: 5).

The great goal of the twenty-first century is that of environmental preservation. The need to provide ecological quality of life. Therefore, “in order to create communities, besides the social and political commitments, it will be indispensable to provide climatic, acoustic, non-polluting and visual comfort to people” (Thwaites et al., 2007: 5). Thus, regeneration takes the meaning of renaturalization, even if this concept cannot be applied wholly as it is used for plants and agronomic issues. Being in an anthropic milieu, renaturalization regives identity and history to the site and provides to the people a sense of home and recognition. This can be achieved by respecting their requirements, both expressed and unexpressed. “A successful neighbourhood should also meet long-term needs – the cycle of a lifetime – in addition to daily needs” (Thwaites et al., 2007: 5). During necessary transformation, aimed at achieving the aforesaid users’ requirements in the built landscape—already existing and preoccupying the urban and peri-urban place—the methodology has to take into account the fact that “the built landscape mobil...