![]() PART I

PART I

Rails and Roads Between Competition and Interdependency![]()

Chapter 1

Rails and Roads Between Competition and Interdependency: a Long and Winding Relationship with Many Innovations That Failed

Ralf Roth

Over the course of the two centuries that led up to 1800, road travel made great progress. Coaches and carriages improved, as did logistical organisation. Post companies enhanced their services to passengers. Then, at the turn of the nineteenth century, a discussion began of some innovative ideas regarding a particular transport system for goods traffic. The ideas concerned iron rails and iron wheels.1 At the beginning of this discussion stood very fundamental considerations. Problems facing transport included the tendency of vehicles to sink in mud, and the fact that they lost energy on unpaved roads due to friction. Smooth, hard surfaces seemed to be needed. It made sense to experiment with paved roads (Steinstraßen), as in the Netherlands, where road builders had become aware of the advantages of hard roads of stone or bricks. But experts spoke more and more of a kind of road made of iron, and in this context there emerged a new form of transport whose speed inspired the imagination of the public at the turn of the nineteenth century.

The railway consisted essentially of three components: rails, flanged wheels and steam engines for propulsion. The wheel-rail system was of fundamental importance. The rolling of the iron wheel on an iron surface brought large savings in energy compared with street transport. The railway was the nineteenth century’s answer to the rough streets of the previous centuries. The new system could be loaded heavily, and had the advantage of ‘minimal friction of the rail’.2 On this point, all the pioneers of railways agreed. Joseph von Baader, for example, pointed out the advantages very clearly:

Instead of rough, bumpy gravel and macadam, or tough and bottomless mud and sludge piles, over and through which the loaded cars often need to be hauled, sometimes when they are sunk up to the hubs of the wheels, a process which is extremely tedious and involves the most violent shocks, the railways approach the ideal of unchanging perfection, independent of the weather’s influence, along permanent paths and mirror-smooth, hard, flat surfaces on which the wheels of the carriages constructed for them roll continuously without shaking.3

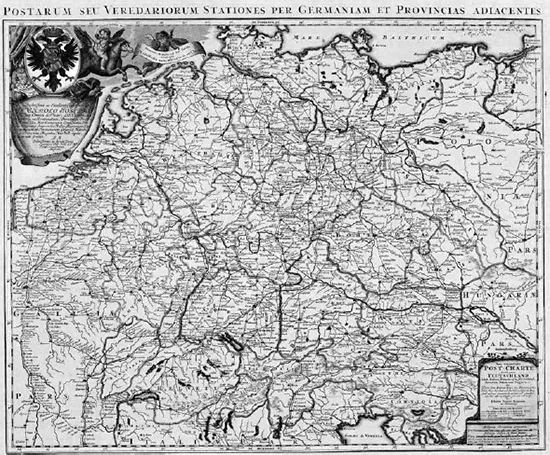

Figure 1.1 Map of Central Europe including postal coach services around 1714

Source: Postroutenkarte from Johann Peter Nell and Johann Baptist Homann 1714. Museumsstiftung Post und Telekommunikation Berlin.

The beginning of the system can be traced back to mining in early modern times. In his Cosmographia Universalis, Sebastian Münster described a wooden railway that had been used in silver mines of the Alsatian Leberthal in the sixteenth century.4 In the eighteenth century, English coal mining entrepreneurs successfully made use of iron fittings on wooden planks and flanged wheels. Here the term ‘railroad’ appeared for the first time; the system achieved considerable success. The first iron rails were relatively thin strips of sheet metal which were nailed on along planks laid down in the direction of travel. The German term for these was Straßbäume; they formed fairly efficient rails. Later on, cast-iron rails were used, including in the British village of Coalbrookdale. John Curr introduced the L-shaped flanged rails made with cast-iron plates in hard-coal mines in Sheffield in 1776.5 In the late 1760s, the Coalbrookdale Company began to fix plates of cast iron to the wooden rails. These (and earlier railways) had flanged wheels as on modern railways, but another system was introduced, in which unflanged wheels ran on L-shaped metal plates – these became known as plateways. John Curr, a Sheffield colliery manager, invented the flanged rail, though the exact date of this is disputed.

Beginning in 1770, cast-iron rails were laid on stone blocks, first at the Derby Canal Railway in Great Britain.6 According to some sources, in the 1730s, the Briton Ralph Allen invented an iron flanged wheel that allowed a more secure drive on rails. According to other sources, iron flanged wheels were not introduced before 1789. Together with flanged wheels came rails with a mushroom-shaped profile, and a strengthening of the network. But the relatively short cast-iron rails were not suitable for the high pressure of the wheels of a running locomotive. In 1820, John Berkinshaw of Durham succeeded in producing rails by rolling. This enabled the creation of rails out of more durable material and in great length – at that time, 15 English feet, that is, 4.575 metres:

The cross-sectional shape was initially the same mushroom shape and support the same also with cast iron chairs on stone blocks. Oddly, it was believed, also of the fish belly shape in the longitudinal direction should not vary and rolled with great difficulty, the wave guide. These tracks are first rolled on a small part of the web-Stocton Darlington [sic] (1825) and on the first large railway locomotive, Liverpool-Manchester (1826–30).7

The advantages of rails were considerable. One horse could now pull several coal wagons at the same time.8 This inspired the imagination of transport reformers. Friedrich Glünder argued that horses used on rails could provide multiples of their current performance.9

Shortly after the first English railway company successfully commenced operation on the line between Liverpool and Manchester, the first railway line in Germany also went into business, running between Nuremberg and Fürth in 1835. But for it to come this far, a series of problems had to be solved. The railway committee had to manage a period of intense work at the construction site, coping with extremely difficult logistical problems there; they had to manage the transport of English locomotives that they would use; and they had to find convincing answers in a fundamental debate about whether a railway was even necessary for the modernisation of the transport infrastructure, or if it would be better to let steam carriages run directly on the streets. Indeed, there were technical alternatives to steam locomotives on rails. Up to the 1840s, discussions went on about the possibility of using compressed air as a driving force.10 Above all, the view persisted that steam engines could drive direct on country roads (chausseen), either as they were, or once they were improved with great effort.

Between 1810 and 1830, that is, parallel to the construction of the first experimental railways, the interest of English transport reformers was attracted by numerous attempts to develop a self-propelled street carriage, a dream that had attracted attention since the Middle Ages. In the thirteenth century, Roger Bacon, a monk and educated person, noted:

One day it will be possible to construct a carriage which moved and will keep moving without being pushed or pulled from any sort of animal.11

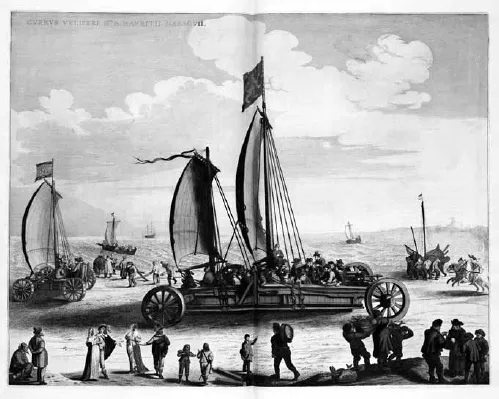

Starting in 1447, so-called Muskelkraftwagen (muscle-powered carriages) appeared on the scene. In 1490, Leonardi da Vinci drew a sketch of an armoured carriage that could be mechanically propelled. A bit more than 100 years later the Dutch mathematician Simon Stevin constructed some land yachts powered by wind that could transport up to 30 people, but these vehicles had some difficulties to keep the direction. From 1650 to 1660, the German mathematician Johann Hautsch sold ornate mechanical carriages (Prunkwagen) which were propelled by muscle force.

In 1674, the Dutch physicist Christiaan Huygens constructed a motor that was driven by gunpowder. Therefore he is seen as a pioneer of the internal combustion engine and one of the inventors of the piston engine. Most automobile motors of today work on Huygens’ principles. But he himself never took his work beyond the experimental stage. Shortly later, in 1680, Sir Isaac Newton presented the concept of a steam mobile, which was realised 80 years later by the Scottish engineer James Watt. In the 1760s Watt enriched the debate about a steam engine with some fundamental suggestions and in 1768 he constructed a first working model of his ideas. He patented both his invention of a steam engine and its use as a carriage drive. From this moment on it was only a short step to the construction of a self-propelling unit by transferring the kinetic energy back to the transport mechanism of the engine. Indeed, the first attempt followed soon, only two years later but not by Watt.

Figure 1.2 Land yacht made by Simon Stevin for Prince Maurice of Orange, 1649

Source: Wikimedia Commons (http://de.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Datei:Simon_Stevins_zeilwagen_voor_Prins_Maurits_1649.webp) (last accessed 14 March 2012).

Simon Stevin built two land yachts for Prince Maurice, who used them on the beach to entertain his guests.

In 1770 Josef Cugnot experimented with a steam carriage that would serve as a tractor for cannons. It was envisioned that the carriage he invented could also serve on roads. Independent from him and independent from James Watt, Oliver Evans had thought about the concept of a steam mobile and took a ride with his own experimental model through the streets of Philadelphia in 1797.12 The previous year, William Murdoch, an engineer employed by Watt, had built a small model carriage; this inspired Richard Trevithik, another inventor, to become interested in steam mobiles. In 1801 Trevithick built the first steam coach and drove it through Camborne near Plymouth. Later on he introduced the machine to the public in London. Other inventors followed between 1814 and 1830, including Major Pratt, John Stevens, William Palmer, Thomas Tindall, Joseph Reynolds, David Gordon, Julius Griffiths, Burstall of Edinburgh and J. Hill of London.13 Their experiments were not without success. Gordon and Burstall undertook serious attempts to develop steam coaches to technical and commercial functionality and Goldsworthy Gurney installed a regular steam omnibus transport between the city of London and some suburbs in 1822. A bit later Walter Hancock followed with the establishment of the London and Paddington Steam Carriage Company.14 All these attempts were carefully monitored by Michael Alexander Lips, one of the ‘busiest apostles of highway steam transport (Chaussee-Dampffahrt)’ as von Baader ironically wrote.15

The outlook was indeed promising because there were some attractive arguments for a rail-less steam transport system. All of these arguments seemed to solve a problem of the rail system. Railways as transport facilities are a directed system with limited possibilities for individual and free use. In the 1820s and 1830s this disadvantage directed the attention of transport reformers to steam carriages without rails. With such carriages it would have been possible to make use of existing roads and streets, and therefore to avoid heavy investments in a totally new and costly infrastructure of rails. The renovation could have been limited to a modernisation of the fleet of coaches and carriages. Moreover, and probably of even greater importance, this would have allowed the mechanisation of independent and individual transport. It would have made it easy for existing companies in the post and freight sectors to ...