![]()

1 Of idols and idylls

The question of national image

What is national image? Like many seemingly straightforward questions associated with concepts in the social sciences, the answer becomes increasingly difficult as one tries to articulate it, particularly given that defining the term necessarily leads one into the treacherous conceptual thickets of national identity and nationalism. Is national image the mental picture conjured up when a country or its people are referenced? In part, the answer is yes. Is it the reputation that a country trades on in the international marketplace? Again, the answer is yes. Is it the raw material from which jokes and satire are formed? But of course—it is all these things and more. Simply put, national image is a fluid, socially constructed view of a nation, and it exists on both the domestic and foreign levels. When one thinks of Switzerland, one undoubtedly conjures up visions of snow-covered Alps, Emmental cheese, discreet bankers, the distinctive white cross on a red field, and Heidi (among other things). These fairly arbitrary examples represent physical geography, local products, emblematic occupations, symbols, and literary/artistic referents. A similar exercise could be conducted for many countries in the world: the Great Plains, hot dogs, the cowboy, the stars-and-stripes, and Superman (United States); the Cotswold Hills, beans on toast, the London bobby, the Union Jack, and Sherlock Holmes (United Kingdom); the Loire Valley, the baguette, the winemaker, the tricoleur, and Marianne (France). However, despite the ease with which we can explain national image in a commonsensical fashion, there is a surprising lacuna in analysis of the concept.1

Towards a holistic understanding of national image

National image is a human construct that exists only when a significant portion of humanity can agree on a basic set of markers that distinguish one nation from another (and—ideally—all others).2 Being a “multidimensional construct,” its sources include both “discursive and non-discursive elements” (Wang 2008, 9). Like other images, national image can exist in a variety of forms: graphic (pictures, symbols, designs, statues); optical (mirrors, distortions, reflections, projections); perceptual (sense, data, appearances); mental (dreams, fantasies, ideas, memories); and verbal/textual (descriptions, idylls, epics, metaphors) (see Mitchell 1986; Beller 2007a). To be more precise, national image functions as a synecdoche for vast, complex, and ultimately unknowable (yet still imaginable) congeries of places, things, peoples, experiences, and ideas. Moreover, we should not forget that such visions of the nation carry with them requisite affective components, i.e., intangibles that provoke a set of feelings that can come to function as a form of intelligence for navigating the world (see Thien 2005; Thrift 2008; Pile 2010).

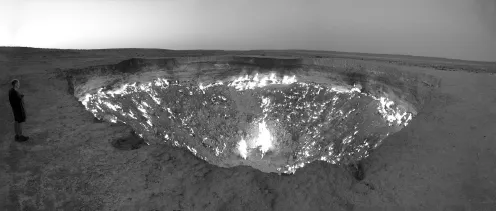

Geography is a central component of any national image, as a nation without a (current or historical) “place” is an entity which has yet to come into being (though certainly, we can conceive of such a phenomenon in a post-national future). Most states have statuary or architectural icons which are immediately recognizable: Russia’s onion-domed St. Basil’s Cathedral, Greece’s Parthenon, India’s Taj Mahal, and Brazil’s Christ the Redeemer. Each of these iconic man-made monuments instantly conveys information. Other countries lay claim to landscapes that possess such powerful evocations that they literally “own” certain types of geographies: fjords (Norway); precipitous karst islands (Vietnam); polders (Netherlands); or the 45-year-old burning gas crater labeled the “Door to Hell” (Turkmenistan; see Figure 1.1). However, uniqueness is not necessarily required to evoke national image, particularly in the instances of agricultural products and foodstuffs. In certain cases, a country’s image is so deeply intertwined with a given thing that it functions as a mnemonic device for calling up larger associations: sushi (Japan), pad Thai (Thailand), Guinness stout (Ireland), or kielbasa (Poland). Symbols are perhaps the most straightforward communicator of national image; the maple leaf (Canada), the black, double-headed eagled (Albania), the Star of David (Israel), and the cross of the Knights Hospitaller (Malta) are just a few examples of how a signifier can come to represent the nation-state in a “condensed form” (Jourdan 2007, 436).3

Traditional occupations and lifestyles can also evince the nation, e.g., the Argentine gaucho, the Burmese monk, the Italian gondolier, and the Iranian bazaari. Likewise, famous individuals—living or dead—can elevate a country’s prestige and serve as powerful agents of national image: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (Turkey), Toussaint L’Ouverture (Haiti), Nelson Mandela (South Africa), or Fidel Castro (Cuba). Imaginary entities or quasi-historical personages—forged in myth, literature, or popular culture—enjoy similar power, from Don Quixote (Spain) to Hayk (Armenia) to Count Dracula (Romania) to the Queen of Sheba (Ethiopia). Systems and structures of government, as well as political culture, are also key elements of any country’s national image, both for its residents and for foreigners. While this is not the forum for interrogating each and every nation’s quiddity, social scientists have not been shy about articulating the unique set of characteristics, otherwise known as stereotypes, that define a given nation’s (mythical) character. The Swedes, for example, are rational, effective, predictable, harmonious, and independent (O’Dell 2011), the Uzbek national character is defined by duty, hospitality, courtesy, musicality, and a poetic nature (Allworth 1990), Mexicans are defined by machismo, a “different sense of time,” and a socio-cultural uniqueness associated with mestizaje (Castañeda 2012), while the Latvians are nature-loving, self-reliant, risk-averse, reserved, and modest (Mežs 2010).

National images can be ancient, e.g., that of Egypt, or nascent, such as is the case with Namibia (1990), Kyrgyzstan (1991), Timor-Leste (2002), and Kosovo (2008). In the globalized world of fast-moving digital data, national images are increasingly influenced by more transient icons. New idols—be they celluloid, televisual, or YouTube-based—can easily trump venerated national symbols rooted in literature or history: Crocodile Dundee serves as the face of Australia, Borat speaks for Kazakhstan, Shakira personifies Colombia, and Mel Gibson’s “Braveheart” (William Wallace) is the apotheosis of an independent Scotland. Corporate brands can now lend their power to national brands, feeding off and feeding into international recognition: LG is synonymous with South Korea; Nokia means Finland; BMW connotes Germany; and Al Jazeera cannot be disentangled from Qatar. Sports figures and teams also add to national image in the contemporary world, with Novak Djokovic influencing how Serbia is viewed abroad, just as Yao Ming redefines the role of China in the world, cricketer Imran Khan shapes Pakistan’s international image, and Didier Drogba makes the Ivory Coast a known quotient around the globe.

Mega-events can also lend power to national image in the era of deterritorialized media, from royal weddings to the hosting of environmental or peace summits to major international sporting events (Giffard and Rivenburgh 2000). Taken together, these impressions often provide what one scholar calls a “quasi-statistical appraisal of the country’s domestic and international performance” (Amienyi 2005, 73). However, it is important to note that all national images of foreign peoples and places are derived through a highly selective process based on value judgments which are informed by the state, travel writers, cultural producers, and other preceptors of “knowledge” (Beller 2007a). These and other contemporary inputs into national image will be explored in greater depth in the following chapter.

While there is little in the way of an established body of literature on the concept of “national image,” much ink has been spilled on the origins, nature, and outcomes of nationalism as well as its compositional essence: national identity; however, less has been written on the idea of national image. Yet, it is impossible for one to exist without the others. Consequently, it is appropriate to provide an aperçu of these concepts before moving on to a more nuanced analysis of national image.

Related concepts: Nationalism, national identity, and national character

To fully understand national image, it is necessary to explore a variety of linked concepts, including nationalism, national identity, national character, and national stereotypes. Each of these fields of inquiry impacts national image, shaping how a given national polity is viewed by its own members and—more importantly from the perspective of this text—how other nations view that particular national grouping. As Nicholas J. O’Shaughnessy reminds us:

According to another author, “In each country the creation of a national image was undertaken by those with power in reference to other national images, because only through this globalization did these images make sense. A relatively clear ‘standard’ of nationalism thus emerged” (Tenorio-Trillo 1996, 243). Taken together, these “pulls” on national image suggest a deep and abiding link to the concept of nationalism, which— unlike national image—is a perennial topic of study across multiple disciplines.

Nationalism is, at its root, an ideology that espouses a perilously simple maxim: each nation should maintain political, social, cultural, and economic control over the territory in which its peoples reside (see, for instance, Deutsch 1953; Gellner 1983; Hutchinson and Smith 1994; Guibernau 1996).5 The ideology of nationalism is constructed and maintained through a complex system, or—using a more contemporary analogy—a web, of competing and complementary power dynamics. As ideologies with a life of their own, particular nationalisms are educed over time, the product of much work by political, economic, and cultural elites. Nationalism, once formed, is reinforced and sometimes transformed through three principal forums: politics, education, and popular/high culture (see Kohn 1944; Motyl 1992; Breuilly 1994; Kramer 2011). Nationalism is impossible without the existence of an “Other,” and more specifically a host of various national Others, including internal Others of a regional, ethnic, linguistic, and/or religious persuasion (Neumann 1999; Kligman 2001; Wingfield 2003; Rash 2012; Alami 2013; Burton 2013). From a historical perspective, the modern form of nationalism spread across Europe and then outwards to all corners of the globe through political structures, which—ironically—undid rather than buttressed imperialism, the primary medium for the spread of nationalism. At the risk of oversimplifying the types of nationalism, it is possible to divide the various nationalisms into two varieties: ethno-nationalism and civic nationalism. The former is rooted in imagined ties of a common ethnogenesis, or blood ties (jus sanguinis). The latter is forged through allegiances and experiences related to a national community determined primarily by birth in a particular state (jus soli) and adherence to a creed associated with that state.6 While there has been a surfeit of academic analysis on the emergence of postmodern nationalism in recent decades (see, for instance, Buell 1994; Ong 1999; Croucher 2004; Calhoun 2008), these two forms of nationalism remain an important binary in the field of study.

National identity links the internal and the external senses of self, producing a “fellow feeling” between members of the same nation, combined with an awareness of difference from other nations (see Smith 1991; Anderson 1991; Cameron 1999; Edensor 2002; Gottlieb 2007). In short, national identity is a “state of mind” (Beller 2007a, 12). Basic elements required for a distinct national identity are (at a minimum): association with a particular territory or homeland (or lack thereof); the political will to be a single people; a belief in a set of common values; and a mass culture (Smith 1991). Similar to nationalism, national identity is reliant on the triad of the military, public school system, and mass media for its fecundity; however, national identity can also flower outside and even in opposition to state support where other avenues of expression come to the fore (sport, mutual aid, religious ties, cultural production, etc.). National identity is produced through a variety of means: visual/performative (music, theatre, art, ceremony, athletic competition); narrative (oral traditions, epic songs, myths, discourses, histories); affect (emotional work, sense of belonging, memory); and association (pledges, affirmations, communal events, collective service). A myth of common descent (“ethnies”) is a typical, though not requisite, element of many nationalities (Smith 1988). The borders of national identity are informed by a variety of markers, often jealously policed by society to maintain distinctions between “in” and “out” groups (see, for instance, Joireman 2003); these include language/dialect, religion/sectarian divisions, dress/appearance/mannerisms, cuisine, sport, celebrations/holidays/veneration of heroes, and other fo...