eBook - ePub

Architecture and Science-Fiction Film

Philip K. Dick and the Spectacle of Home

- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The home is one of our most enduring human paradoxes and is brought to light tellingly in science-fiction (SF) writing and film. However, while similarities and crossovers between architecture and SF have proliferated throughout the past century, the home is often overshadowed by the spectacle of 'otherness'. The study of the familiar (home) within the alien (SF) creates a unique cultural lens through which to reflect on our current architectural condition. SF has always been linked with alienation; however, the conditions of such alienation, and hence notions of home, have evidently changed. There is often a perceived comprehension of the familiar that atrophies the inquisitive and interpretive processes commonly activated when confronting the unfamiliar. Thus, by utilizing the estranging qualities of SF to look at a concept inherently linked to its perceived opposite - the home - a unique critical analysis with particular relevance for contemporary architecture is made possible.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Science-Fiction, Architecture, and Home

I am far from the first to insist that science fiction ought to be read with much closer and more alert attention than it usually has been.1Carl Freedman, Critical Theory and Science-Fiction[Films] about space exploration, alien life forms, and the origin of the universe are implicitly about humanity’s quest to find our place in the time/space continuum—to feel “at home” in the universe.2Susan Mackey-Kallis,

The Hero and the Perennial Journey Home in American Film

The notion of home can be seen as a foundational concept in popular SF as the point of departure or place of return in the space odyssey, time-travel mission, or heroic quest. To name but a few examples in American cinema, E. T. desperately yearns for it; the destruction of Luke Skywalker’s home prompts him to embark on his heroic adventure; like Jim McConnell in Mission to Mars (2000), Roy Neary abandons his home for one of another sort in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977); Scott Carey is trapped in his home in The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), and it is the transparent theme of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986). The home is also a common theme in British SF as evidenced by Thomas Newton’s homesickness in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), the revival of the Doctor Who (2005-) television series, Garth Jennings’s adaptation of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (2005), and Duncan Jones’s Moon (2009). Meanwhile, the role of the home is also evident in such international SF classics as Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972) which starts and ends with images of protagonist Kris Kelvin’s country house, or Russian dacha. The notion of home is also parodied in such SF films as A Clockwork Orange (1972) and The Stepford Wives (1975, 2004). In fact, most SF narratives seemingly center on notions of homelessness, homecomings, threats to and invasions of home, and journeys from it. Independent of the film’s narrative, however, home is also considered within SF as the place of the audience member, spatially and temporally, the distinction of which is critical for establishing the alien encounter with the putative future world.

As a critical genre, SF offers insights into the contemporary milieu that have significant implications for all areas of cultural research and specifically, as I will argue here, for architecture. As Anthony Vidler states,

Film, indeed, has even been seen to anticipate the built forms of architecture and the city: we have only to think of the commonplace icons of Expressionist utopias to find examples, from Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari [1920] to Metropolis, that apparently succeeded, where architecture failed, in building the future in the present.3

While there has been significant interest within architectural literature related to Vidler’s enthusiasm for the prescience of SF, representations of home are often overlooked in favor of the apparent innovations and special effects on-screen. My intent here is, therefore, to elevate the discussion of home in SF from its often abstract engagement by architectural texts. More specifically, I will examine how notions of home are represented through various SF designed environments and intimate how such an analysis might inform contemporary architectural design strategies. I will ultimately position the notion of home as an essential link between SF and architecture with the goal of contributing to the rather limited number of existing studies of SF in architectural discourse.4

In the twenty-first century, the SF genre increasingly extends into various other realms such as comic books, video games and online communities; however, I will focus on film because it remains one of the primary mechanisms of cultural projection at this time and relies heavily on the mise-en-scène, including its architecture, to tell its story. The film industry, as a powerful artistic medium, also exerts a strong influence on popular culture, benefiting from vast resources and attracting elite design talent. Furthermore, while television series such as Star Trek, Battlestar Gallactica, Stargate, V, and Doctor Who, with substantial fan bases and critical narratives worthy of discussion, closely follow film in terms of visual spectacle and special effects, the set designs and production of the larger budget films generally provide more substantial environments for such an architectural investigation. Focusing on film rather than trying to circumscribe the entire SF genre, the following chapters will be largely theoretical in nature, allowing the various film settings and production designs, along with the narratives that inform them, initiate the architectural discussion. I also recognize that Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) would not exist without Arthur C. Clarke, Solaris (1972, 2002) without Stanislaw Lem, or Johnny Mnemonic (1995) without William Gibson, and will thus occasionally include SF literature throughout. In fact any SF film, if not relying entirely on literature for both narrative and visual cues, has been influenced by a long and rich literary tradition and I will honor that tradition with Philip K. Dick emerging as a central influence.

We use the term home to describe a multitude of conditions from houses, towns, and homelands to vacation homes, homepages, and home planets. Given the fluidity and mobility of contemporary postmodern society, the concept of home in all areas of cultural enquiry remains a prominent one. With a developed understanding of the convergence of home, architecture, and SF, we will be better positioned to explore how notions of home are projected on-screen and what can be gleaned from them for contemporary architecture. Yet in order to fully understand the potency of SF as an architectural tool, it is necessary to initially shift one’s focus from the often spectacular imagery of the genre and examine the cultural role of SF, or as Annette Kuhn terms it, it’s “cultural instrumentality.”5 Hence, we begin by analyzing SF as a cultural genre centered on the notion of home.

Notes

1 Carl Howard Freedman, Critical Theory and Science Fiction (Hanover, 2000), p. xviii.

2 Susan Mackey-Kallis, The Hero and the Perennial Journey Home in American Film (Philadelphia, 2001), p. 198.

3 Anthony Vidler, “The Explosion of Space: Architecture and the Filmic Imaginary,” in Film Architecture: Set Designs from Metropolis to Blade Runner, ed. Dietrich Neumann (New York, 1996), p. 13.

4 Others presently exploring the crossovers of SF and architecture are identified in Chapter 4.

5 Annette Kuhn, Alien Zone: Cultural Theory and Contemporary Science Fiction Cinema (London, 1990), p. 1.

1

Defining Science Fiction: Darko Suvin and the Genre

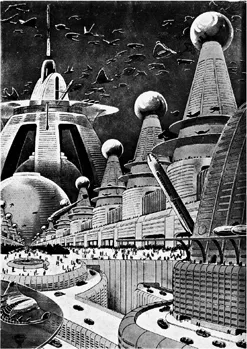

1.1 “City of the Future” by Frank R. Paul (back cover of Amazing Stories magazine, August 1939)

The term “science-fiction” resists easy definition.1Adam Roberts, Science Fiction: The New Cultural Idiom[One] can see how vital a role fiction has played in the development of culture. How could one not? But as John Gardner pointed out, fiction is ultimately to be grounded in our common experience of the world outside fiction if, in our cultural life and ultimately our everyday life, we are not to spiral endlessly away from reality.2Michael Benedikt, For an Architecture of RealityAn image soon stops persuading or even making any impression at all if it disconcerts us at no cost, without any element of truth.3Roger Caillois, “The Image”

Defining SF in Literature

SF is a radical starting point for architectural discourse, particularly if we look initially beyond the formal qualities of the buildings and special effects on-screen. Thus, the essential first question to ask is—what is sciencefiction? While this appears at first to be a rather straightforward query, genre distinctions are increasingly suspect and thus necessitate some critical deliberation. According to Gül Kaçmaz Erk the term was first coined by Hugo Gernsback in his 1929 novel Ralph 124C41+ and is defined by Erk as, “fiction based on imagined future scientific or technological advances and major social or environmental changes.”4 Andrew Milner, citing John Clute and Peter Nicholls, instead argues Gernsback coined the term “scientification” in 1926 but that “science fiction” was not used commonly until John W. Campbell Jr. changed the name of a “pulp” publication called Astounding Stories to Astounding Science Fiction after 1938.5 While Erk’s definition may appear to be an acceptable position from which to proceed with an architectural discussion, the debate within SF criticism warrants closer attention as this is essential to our current inquiry into the concept of home. SF has long been linked to various genres, most

SF has long been linked to various genres, most commonly utopian, horror, and fantasy, but while the “sci-fi/fantasy” label may serve its purpose on DVD ren...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part One: Science-Fiction, Architecture, and Home

- Part Two: Re-visioning Home in Dick-Inspired Films

- Part Three: Go Home – I’m Home – Becoming Home: Architecture and Grammar in SF

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Architecture and Science-Fiction Film by David T. Fortin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.