- 478 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

In the recent decades, laser cooling or optical refrigeration—a physical process by which a system loses its thermal energy as a result of interaction with laser light—has garnered a great deal of scientific interest due to the importance of its applications. Optical solid-state coolers are one such application. They are free from liquids as well as moving parts that generate vibrations and introduce noise to sensors and other devices. They are based on reliable laser diode pump systems. Laser cooling can also be used to mitigate heat generation in high-power lasers.

This book compiles and details cutting-edge research in laser cooling done by various scientific teams all over the world that are currently revolutionizing optical refrigerating technology. It includes recent results on laser cooling by redistribution of radiation in dense gas mixtures, three conceptually different approaches to laser cooling of solids such as cooling with anti-Stokes fluorescence, Brillouin cooling, and Raman cooling. It also discusses crystal growth and glass production for laser cooling applications. This book will appeal to anyone involved in laser physics, solid-state physics, low-temperature physics or cryogenics, materials research, development of temperature sensors, or infrared detectors.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Laser Cooling of Dense Gases by Collisional Redistribution of Radiation

1.1 Introduction

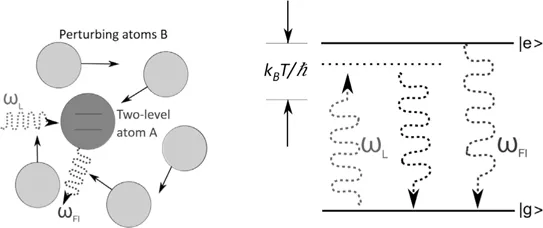

1.2 Redistribution of Radiation

1.2.1 Basic Principle

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Laser Cooling of Dense Gases by Collisional Redistribution of Radiation

- 2. Laser Cooling in Rare Earth-Doped Glasses and Crystals

- 3. Progress toward Laser Cooling of Thulium-Doped Fibers

- 4. Laser Cooling of Solids around 2.07 Microns: A Theoretical Investigation

- 5. Optically Cooled Lasers

- 6. Methods for Laser Cooling of Solids

- 7. Deep Laser Cooling of Rare Earth-Doped Crystals by Stimulated Raman Adiabatic Passage

- 8. Bulk Cooling Efficiency Measurements of Yb-Doped Fluoride Single Crystals and Energy Transfer-Assisted Anti-Stokes Cooling in Co-Doped Fluorides

- 9. Interferometric Measurement of Laser-Induced Temperature Changes

- 10. Fluoride Glasses and Fibers

- 11. Crystal Growth of Fluoride Single Crystals for Optical Refrigeration

- 12. Microscopic Theory of Optical Refrigeration of Semiconductors

- 13. Coulomb-Assisted Laser Cooling of Piezoelectric Semiconductors

- Index