![]()

1 How and when does open innovation affect creativity?

Eric Schenk, Claude Guittard and Julien Pénin

Introduction

Over the last decade, open innovation (hereinafter referred to as ‘OI’) has received increasing attention from both researchers and practitioners. The focus has been mainly placed on business model aspects of OI, which include IP issues, access to external resources and markets, absorptive capacity, etc. This chapter more specifically addresses the impact of OI on individual and organizational creativity.

In our view, creativity encompasses individuals’ ability to generate new relevant ideas and concepts, as well as out-of-the-box problem solving capabilities. There is a usually a general (often implicit) consensus that OI has a positive effect on creativity. By opening up their boundaries and interacting with other actors, firms may avoid falling into an incremental trap and/or avoid the innovator dilemma (Christensen, 1997). Moreover, the literature shows that openness and information sharing may have a positive effect on problem solving (Boudreau and Lakhani, 2013; Brabham, 2008).

However, OI involves many different modalities. It can be highly or weakly interactive, market or non-market based, formal or informal, exploration or exploitation oriented, etc. Depending on the modality that is chosen, the implications for creativity may be different. OI may sometimes enhance creativity but also, in other cases and contexts, have no impact at all, or even a negative impact on it. For instance, when a pharmaceutical multinational buys a licence for a life science start-up company, it usually has no impact on creativity. On the contrary, OI can be seen here as a consequence of the lack of creativity of the pharmaceutical firm, which therefore obliges it to compensate and buy a licence.

The objective of this chapter is therefore to use the existing literature and case studies in order to discuss how and when OI affects creativity. An important point in our reasoning is that, since creativity is described as an ability, OI must affect firms’ innovative process, routines and knowledge in order to increase it. If it only aims to develop new technology that can be exploited without changing routines and the innovation process, then OI, although it may increase the innovative performance of the process, will have no impact on its actors’ creativity. This leads us to distinguish two radically different types of OI modalities: the ones that only aim at reorganizing the innovation process (and follow a pure logic of resource allocation) and the ones that aim at co-creating new resources. In our view, only the second ones can have a significant effect on OI actors’ creativity (although the first ones can significantly improve the efficiency of the innovation process).

In the following section, we introduce the concepts of creativity and OI that are used in this chapter. We then present OI modalities targeted at resource allocation and question their impact on firms’ creativity, with the example of markets for technology and crowdsourcing. In the next step, we consider cases where OI sustains resource co-creation and show that in these cases, the effect on creativity can be significant. The example of knowledge communities is used to back the argument. The last section concludes.

What do we mean by creativity and open innovation?

Providing a comprehensive review of creativity and OI goes beyond the scope of this chapter. However, given the multiplicity of approaches in the literature, it is important to clarify in which way we use these concepts.

Creativity and the innovation process

Although innovation is known to have various potential targets, we mainly focus on product innovation and the new product development process (e.g., Pahl et al., 2007; Ulrich and Eppinger, 2012). However, as shown, for instance, by Lenfle (2005), some insights into product development can also be applied for an analysis of new service development. New product development is often viewed as a ‘stage-gate’ process (e.g., Cooper and Edgett, 2012). First, the ideation phase is a period in which new concepts emerge. This phase, sometimes referred to as the Fuzzy Front End (Khurana and Rosenthal, 1998; Gassmann and Schweitzer, 2013; Cohendet et al., 2013), usually gives room to creativity, for instance, by the use of brainstorming methods or crowdsourcing. After this first step, some concepts are selected and a phase of business analysis is entered in which market as well as financial opportunities are assessed. After the business case analysis, another selection takes place leading to the development phase for a few projects. The aim of the development phase is to find cost effective and reliable ways to implement the concepts that have been selected previously. Therefore, this phase is very much problem solving oriented. The last steps imply the testing and validation of previously developed concepts and solutions, and finally the market launch.

Our general assumption is that creativity is required throughout the innovation process. In the early stages, creativity is targeted towards the emergence of new ideas. This process can be rather open and unstructured (hence the term ‘fuzzy front end’) and it is related to a rather classical view of creativity (emergence of novel useful ideas). Later in the innovation funnel, creativity is employed in the problem solving process. Indeed, solving new problems often implies the ability to think out of the box and to depart from methods and techniques that are usually employed).

Creativity can be viewed as the outcome of an individual process. According to the componential theory of creativity (Amabile, 1996, 1998; Amabile et al., 1996), individual creativity is related to domain specific skill, creative thinking skills, intrinsic task motivation and, finally, the social environment. Domain specific skills refer to competence and expertise which are largely tacit and acquired though personal experience (Ericsson et al., 2007; Bootz et al., 2015). Creative thinking skills include traits of personality, cognitive characteristics such as reasoning and attitude towards risk, and the ability to think ‘out of the box’. Intrinsic motivators include task enjoyment (Deci, 1975) and autonomy, mastery and purpose (Pink, 2015). Finally, environmental factors refer to the work environment, which includes relationships with colleagues and the hierarchy, but also the job design and incentive schemes of the organization. Creativity is therefore influenced by individual, idiosyncratic factors, as well as by external factors. It can be noticed that the environmental factors can have a positive or a negative impact on creativity (Amabile and Kramer, 2011). For instance, according to the overjustification effect (Deci et al., 1999), extrinsic motivators can impede creativity by crowding out intrinsic motivation.

A complementary approach to creativity is proposed by Woodman et al. (1993) who define organizational creativity as the ability of an organization to stimulate interactions between individuals in a complex social setting. Organizational creativity depends on individual characteristics, group characteristics and organizational characteristics. Recent studies (Hargadon and Bechky 2006; Parjanen, 2012) have further analysed the notion of group creativity. For instance, according to Parjanen (2012), collective or group creativity can be stimulated by the strategy of the organization, the type of leadership, the organizational culture, and the tools and methods supporting creativity. According to these authors, group creativity is relevant for complex tasks that require multiple skills, and which cannot be dealt with individually. In this context, social interactions and knowledge sharing are especially useful in overcoming individual perceptions (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995).

A primer on open innovation

OI is an umbrella term that means that the innovation process is interactive since innovators today can no longer remain isolated or entirely self-reliant (Chesbrough, 2003; Pénin et al., 2013). OI is thus opposed to the romantic vision of the lone entrepreneur who heroically breaks down all barriers in order to bring the innovation to the market. On the contrary, in OI logic, the entrepreneur interacts with his or her environment at different stages of the innovation process, forging links with other innovation stakeholders, public research centres, suppliers, customers or even actual or potential competitors. OI is thus more or less synonymous with collaborative, modular or collective innovation, many terms that are sometimes found in the literature and which mean that innovation is a matter of collaboration and more or less formal interactions.

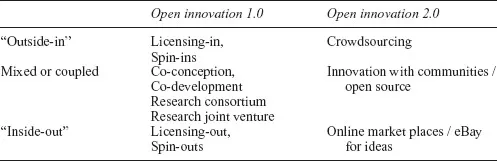

The modalities of OI can be very different (see Table 1.1): formation of a research joint venture between different organizations, exchange of intellectual property licences, formation of patent pools, agreements on industrial standards, formation of innovative clusters, outsourcing of problems on Internet platforms (crowdsourcing), interactions with open source communities, etc. Jullien and Pénin (2014) provide a classification of OI modalities according to the importance they give to ICTs (OI 1.0 versus 2.0) and the inside-out versus outside-in nature of knowledge flows.

Table 1.1 Types of open innovation (Jullien and Pénin, 2014)

Indeed, the literature generally distinguishes two sides of OI: the ‘inside-out’ and the ‘outside-in’. Both sides are based on the direction of knowledge and information flows between the company and its environment. Inside-out means that the knowledge flows from the inside to the outside of the company, i.e., it outsources knowledge and technology internally developed by granting licences, creating spin-offs or revealing trade secrets to a collaboration partner. Outside-in means that the knowledge flows from outside to inside, i.e., that the company absorbs knowledge developed by others, for example, by buying intellectual property licences, absorbing other companies or by setting up ‘crowdsourcing’ contests. Often, the OI process is also called coupled, that is to say, it mixes both types of knowledge flows, as is the case, for example, during bilateral collaboration in R&D where both partners generally exchange individual information.

Chesbrough does not hesitate to speak of a new paradigm in order to describe the rupture induced by OI. But for other authors it is possible to find examples of OI during most periods of the past, thus suggesting that the OI concept is nothing more than a recycling of previous concepts, a very successful marketing operation, i.e., ‘old wine in new bottles’ (Trott and Hartmann, 2009). However, OI still carries original elements. In particular, the emphasis put by Chesbrough on the inside-out aspect and the importance of open business models are absolutely new. Moreover, the use of ICTs, and especially the Internet, has changed the situation by allowing OI to be far more open and interactive today than in the past. ICTs multiply the possibilities of remote interactions and facilitate the links between several partners and the development of innovative communities. The modalities of OI today are therefore sometimes very different from those that could be observed even in the last few decades. To illustrate this change, Jullien and Pénin (2014) speak of OI 2.0 versus 1.0 (see also Rayna and Striukova, 2015).

Open innovation as a pure resource allocation process

Seeking to understand if OI improves organizational creativity in the innovation process, we distinguish between two very different cases of OI: OI as a pure resource allocation process and OI as a knowledge co-creation process. We argue in this section that in the first case, the impact on organizational creativity is likely to be marginal.

Resource allocation versus knowledge co-creation

Many cases of OI only aim at better allocating the resources used in the innovation process. It therefore follows a pure logic of optimization of existing resources which does not affect, or only marginally, the cognitive capacity of the actors in the innovation process. For instance, many examples of crowdsourcing of inventive or creative activities or of in-licensing only aim, for the company that crowdsources a problem or buys a patent licence, to substitute internal R&D with external R&D. Similarly, many bilateral collaborative agreements only aim at improving the exploitation of an already existing invention by, for instance, optimizing the supply chain, etc.

In this case, OI is a way to make the innovation process more efficient. In the end, thanks to OI, the global innovative performance of the system is improved and more innovations reach the market, but companies that open up their boundaries as a way to better allocate resources do not become more creative. It may be a way for them to outsource creative work and access more creative things.

On the other hand, some cases of OI, such as, for instance, research joint ventures or open source communities, primarily aim at creating new knowledge by merging different competences and making heterogeneous people work together, thus impacting their cognitive capacity. Those modalities of OI are much more exploratory and within these contexts it is likely that OI not only improves the global innovative performance of the system, but also enhances the creativity of participants because it obliges them to interact actively with other participants. This will be developed later in the chapter.

In the case of a pure resource allocation process, OI does not significantly improve creativity. Rather, OI is a consequence of the lack of creativity of the actors in the innovation process. It can offer them a short-term solution to their lack of creativity, but does not affect their cognitive capacity and does not improve their ability to think out of the box, introduce new concepts, radically test new solutions, etc.

It is possible that the specialization effect induced by a better allocation of resources enhances, to some extent, the skills of actors involved in the innovation process. Yet, we believe that this positive effect is usually overcome by the negative effect of specialization which traps innovators into separate boxes. Indeed, the division of labour and specialization induced by OI contributes to reducing a global problem, which requires interaction between very different participants (thus eventually obliging them to ‘think different’) in a series of independent local boxes, thus reducing interactions between heterogeneous actors and narrowing their research scope. Specialization, even in the case of inventive and complex activities, is likely to reduce the creative impulse of those who perform them.

Markets for technology: does a division of labour ...